Toward a path less riddled

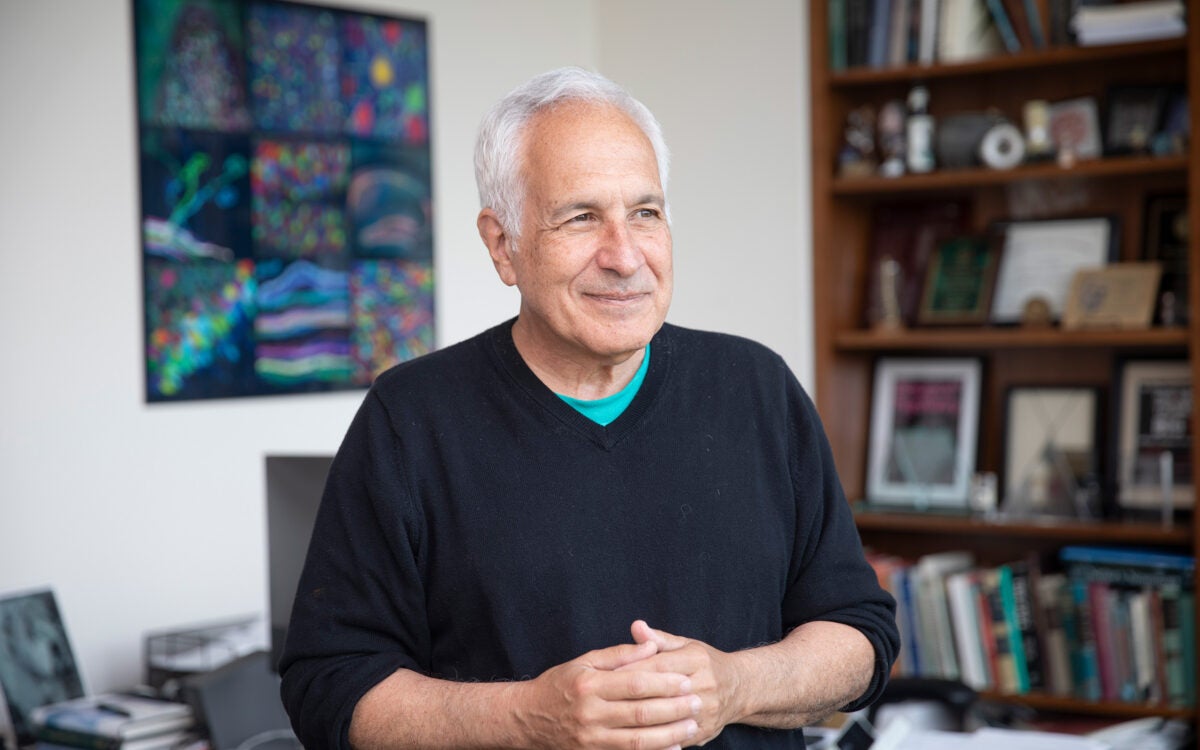

Anthony Abraham Jack has left a mark on campus life

This is one in a series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

While working on his dissertation on how low-income students fare in elite universities, Anthony Abraham Jack heard a certain troubling story one too many times.

Each spring break, students stuck on campus — many of them low-income — faced closed dining halls and had little alternative but a rotation of sandwiches, canned beans, and Ramen instant noodles.

Jack, who was halfway through his doctorate in sociology at Harvard at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, shared his research with school administrators, and the University launched a pilot program in 2014 to keep the dining halls open. This year, the College gave out vouchers, which were also available over winter break.

For Jack, whose findings on economic diversity at elite colleges have brought him national recognition, Harvard’s response was a powerful signal. It meant that his research could improve lives.

It’s a mission he plans to continue in his new position. After receiving his doctorate, Jack will join Harvard’s prestigious Society of Fellows. In three years, he’ll become an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Education and a Shutzer Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

“As long as I have the energy, I’m going to push colleges to create an environment where more students, especially those who are underprivileged, leave colleges whole and healthy,” he said in a conversation at Mather House, where he is the resident tutor. “They can’t leave broken and beaten.”

It’s a story Jack knows well.

The middle son of a single mother who worked as a school security guard, Jack grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Coconut Grove, Fla. An ambitious student from a young age, he attended a magnet program in middle school and a private high school in his senior year on a scholarship.

In 2003, he was offered full financial aid by Amherst College and became the first in his family to go to college.

When Jack graduated cum laude, his class was the most diverse that Amherst had ever seen, he said. His journey from Miami to Amherst drew the attention of The New York Times, which ran an audio feature about an essay he wrote at Amherst. In it, he said that his path was not “from the bottom to the top” because his life before Amherst was not “anywhere near the bottom.”

Jack credits his success to his drive and the support of a tightly knit family. His mother, Marilyn, attended every school activity he participated in. If she and his siblings are his biggest cheerleaders, they also keep him grounded, he said.

Jack uses the term “privileged poor” for low-income students who attend rich high schools, where they acquire social and cultural capital that helps them succeed in college. The “doubly disadvantaged” are low-income students who attend distressed public schools in poor neighborhoods and often struggle in top-ranked colleges.

“If you’ve been in an environment where teachers are authority figures with no contact outside the class, and you were one of 50 students, when you come to Harvard, you’re going to behave the same. You don’t go to office hours, and you don’t feel comfortable talking to professors,” he explained.

When asked whether he’s among the privileged poor, Jack, a genial man with an easy smile, burst into laughter.

“Yes, but I only did private school for one year, which gave me a beautiful introduction to college,” he said, “but not the kind of immersion some of my students had.”

Jack marvels at how much progress has been made since 1998, when Princeton became the first Ivy League university to offer full financial aid to talented low-income students, but he believes more needs to be done.

Of his decision to stay at Harvard, Jack said he hopes to provide a platform to promote changes that can help low-income students make the most of college, and help universities enact policies that can reduce the perpetuation of inequality.

“Harvard gives me the opportunity to talk to the world on behalf of those students who entrusted me with their stories,” he said. “I want to make sure their path is less riddled with hurdles and obstacles.”