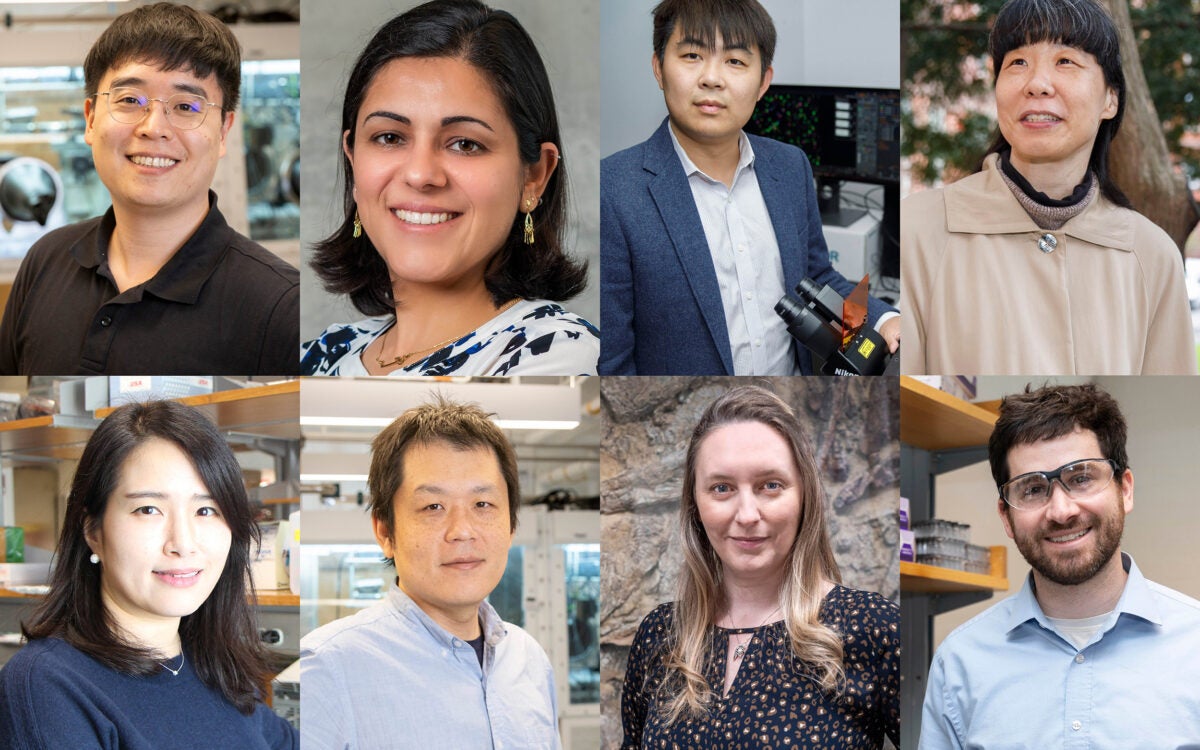

Michael Stein (from left), Tommaso Vitale, and Samuel Moyn speak at a panel on social inequalities hosted by the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. “We have a very big boat to turn, but we see progress,” Stein said.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Mixed progress cited in challenging discrimination

‘Glacial movement of change’ brings hope to some, discouragement to others

Stamping out stigma and broader inequality remains a vexing challenge that requires the tools of both researchers and activists, according to panelists at Harvard University.

Three experts at a panel on comparative inequality cited mixed progress in the effort to advance fairness and social inclusion, touching on discrimination against the Roma people and the disabled, and the rise of inequality in an era of support for human rights.

“It’s a long battle. It’s one that will take many years, but we see progress and we’re quite excited and enthused about it,” Michael Stein, visiting professor at Harvard Law School, said of the global effort to end discrimination against people with disabilities.

But Stein, executive director of the Law School’s Project on Disability, said it is still painful to see how much work remains to be done. “The hardest part of my job is going into places where people are suffering … and who are not happy with the glacial movement of change,” he said.

Wednesday’s discussion was the fourth in a series presented by the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.

Tommaso Vitale, associate professor of sociology at Sciences Po, an international research university in Paris, offered insights gained from his extensive work studying the Roma.

Vitale said the ethnic group, which rejects the term “Gypsy,” still suffers discrimination and hatred, a legacy of centuries of persecution. He said that changes in public policy alone will not address a problem he believes is rooted in negative stereotypes that social scientists help perpetuate.

Scholarly discussions about the Roma, and the focus on “the thesis of persecution, the thesis of cultural loss,” Vitale said, obscures the ways in which individual Roma are working to overcome those obstacles.

“The problem for me is how to change the dominant narrative of Roma, and to understand where and how this dominant narrative is created,” said Vitale, who is also scientific director of Science Po’s Governing the Large Metropolis master’s program.

Vitale said the persistent focus on the hatred of Roma people also fails to reflect variations in that attitude, notably the reduced levels of hostility evident in places where Roma come into close contact with other groups.

“It changes for the level of education,” he said of anti-Roma sentiment. “It changes for the level of general ethnocentrism, it changes for political attitudes. It is extremely sensitive to the kind of place where people live.”

Through the Harvard Project on Disability, Stein has worked with local organizations in more than 40 countries to promote social inclusion and combat stigmatization of disabled people. He also helped draft the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

He said the discrimination is rooted in deeply embedded attitudes that are “fairly consistent around the globe.” Those include social exclusion, paternalism, and assumptions that the disabled are incompetent.

While those ideas persist, Stein said there have been encouraging signs of change, citing the flurry of disability reform laws adopted around the world since the UN convention took effect in 2008.

The most creative work is being done by disabled persons’ organizations, he said, citing the work the Harvard program has done to assist groups in places ranging from Bangladesh to Israel, China, South Africa, and Vietnam.

“We have a very big boat to turn, but we see progress,” Stein said.

Samuel Moyn, professor of law and history at Harvard, discussed how inequality began surging in the mid-1970s just as human rights were supplanting the welfare state as the global framework for promoting social good.

Moyn theorized that the welfare state’s failure to take hold was rooted in indecision among policymakers about whether to pursue the ideal of an egalitarian society or a society that guaranteed sufficiency only.

He said with the arrival of the human rights era, “welfare indecision” gave way to an embrace of sufficiency as the sole aim, a time when “the ceiling in inequality [was] blown away.”

Moyn said it is worrisome that human rights movements by their nature “don’t seem positioned well to create the incentive structure based on fear” that once drove the rich to support policies to redistribute wealth.

The Weatherhead Center will conclude its series next fall with “Social Inclusion and Poverty Eradication.” To read the Harvard Gazette’s special series “The costs of inequality,” visit its website.