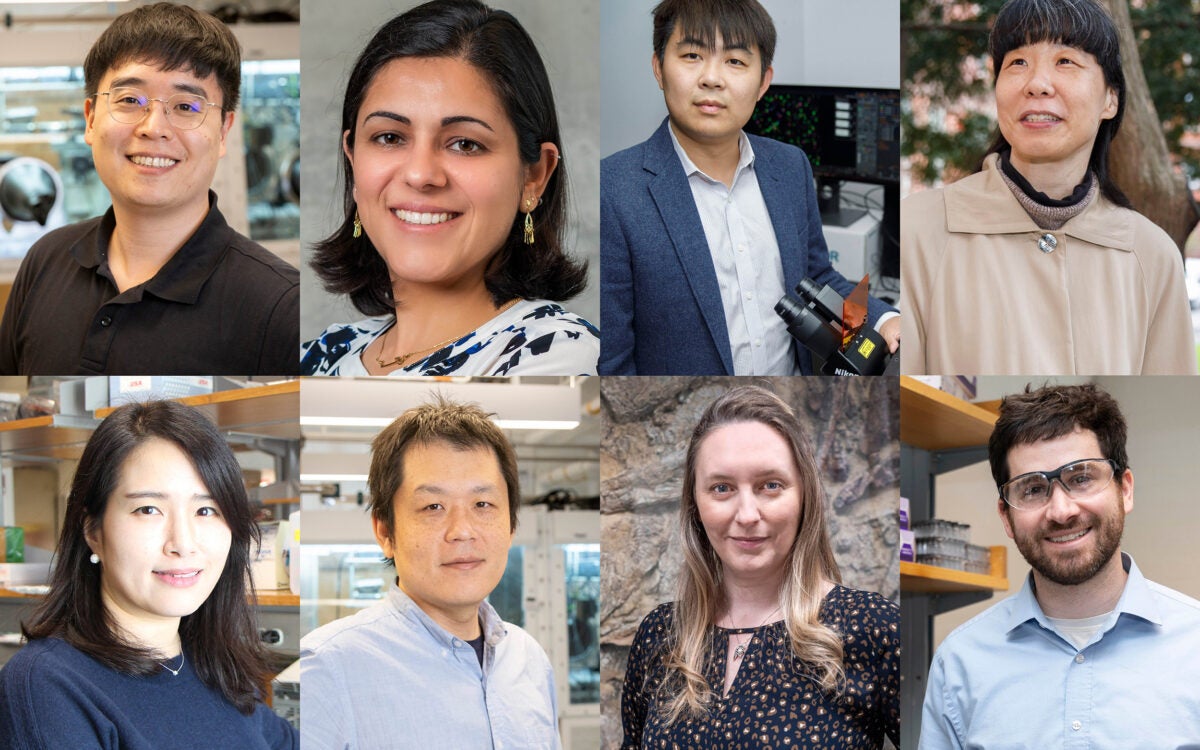

$1M in grants to support 10 climate research projects

Six Harvard Schools gain support from Climate Change Solutions Fund

More like this

Belching smokestacks and idling cars may be the typical scapegoats for climate change, but millions of other factors contribute — sometimes ones we never think twice about, like cracking a window because the heat is too high or small leaks from old gas lines.

As communities around the globe move to dramatically reduce emissions in an effort to curb the impact of climate change, researchers across Harvard are developing new energy technologies and promoting changes large and small to speed solutions on the local, regional, and global levels.

Ten research projects driven by faculty collaborators across six Harvard Schools will share over $1 million in the second round of grants awarded by the Climate Change Solutions Fund, an initiative launched last year by President Drew Faust to encourage multidisciplinary research around climate change.

The projects sound as futuristic as shooting reflective particles into the atmosphere to deflect the sun’s rays — and as down-to-earth as grassroots community campaigns to spark behavior changes at home. But the common threads are creativity and collaboration across a wide range of disciplines, forging an effort in which nontraditional factors of climate change are examined from multiple viewpoints in order to contribute inspired solutions.

“This research wouldn’t happen in our silos,” said Holly Samuelson, an assistant professor of architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, who is working with researcher Jose Guillermo Cedeño Laurent from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The pair will use Harvard’s campus as a “living laboratory” to find a better way to measure the overall climate impact of existing buildings, leveraging data from occupant behavior to improve construction and renovation planning tools for the indoor spaces where we spend most of our time.

Cedeño Laurent has developed a way to passively gather data on occupant behavior through an algorithm that correlates environmental measures like temperature, noise, and carbon dioxide levels with activity data collected from wearable devices — in this case, donned by volunteer Harvard undergrads. The refinements in understanding of occupant behavior are critical to help building professionals design infrastructure that reduces environmental impact and offsets the challenges of changing climate.

“Our goal in life is not to build buildings, but [to] produce some kind of output in those buildings,” said Samuelson. “It’s possible to have very energy-efficient buildings that are very unhealthy, and also it’s possible to waste a lot of energy striving toward health goals in some buildings.”

With the more nuanced occupant behavior data, Cedeño Laurent and Samuelson can develop and test a framework to assess a building’s performance on indoor environmental quality as well as energy use, metrics that tend to be evaluated separately today to the detriment of the green building movement. Using that framework, they will be able to improve the accuracy of the energy models used to evaluate building performance. Through the gathering of human and operational data, patterns emerge — and from patterns, more accurate predictions on occupant behavior and its prompts. Applying these patterns and predictions into energy modeling software could provide new insights for creating eco- and user-friendly spaces.

Currently, energy models are not used as much as they could be due to the costs of customization to each particular design project.

“Out of the box, there are just so many thousands of knobs to turn in these energy simulations. They’re accurate enough to aid in certain design decisions, but to combat climate change, we need a more dependable way to predict the results of riskier investments in building design and operations,” said Samuelson. “We know that our buildings in the developed world operate very poorly across the board, but the problem is that every building is different.”

Samuelson hopes an improved modeling system will become a standard part of design decision-making, not just in new construction but in retrofits and operational decisions. She cited once finding annual savings of $120,000 for a building just in changing operations of the cooling system. Multiply those energy savings times the millions of existing buildings in the country, and the environmental gains and financial payoffs could be huge.

While Samuelson is working on realizing potential energy savings that enhance human well-being, other researchers are trying to accelerate the transition to clean, renewable energy. Alan Aspuru-Guzik, a professor of chemistry and chemical biology, will focus on lowering the costs of solar cells by exploring the use of commercially available organic dyes as the solar energy conversion component.

Aside from their extraordinary adaptability, organic solar cells also carry greater potential for material application — like fabric. Think jackets that could charge your smartphone, or tarps covering rooftops in the developing world.

“Since we started our search for organic solar materials, many things have changed. Manufacturers have lowered the cost for silicon, and a new class of materials has taken the world by storm,” said Aspuru-Guzik, saying that although the market has improved, “organics still have a niche. Where 2 billion people have no access to electricity, their costs will matter a lot.”

Some costs have no dollar amount. Widely touted as more environmentally friendly than other energy sources, new hydroelectric sites release large pulses of the potent greenhouse gas methane into the atmosphere, where it persists for between 10 and 30 years, with global effects.

Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Professor Elsie Sunderland, Daniel Jacob, also of the Paulson School, and James Hammitt of the Chan School are looking at the impact of methane released from dams to try to identify feasible alternatives. The project will track present methane releases, making use of satellite imagery, to help raise awareness of the issue among policymakers and inform decision-makers about future hydroelectric dams.

Sunderland echoed a sentiment from many of the fund’s winners, saying, “That’s one of the reasons I’m so excited that this research has been funded: This will do a lot in terms of starting that dialogue.”