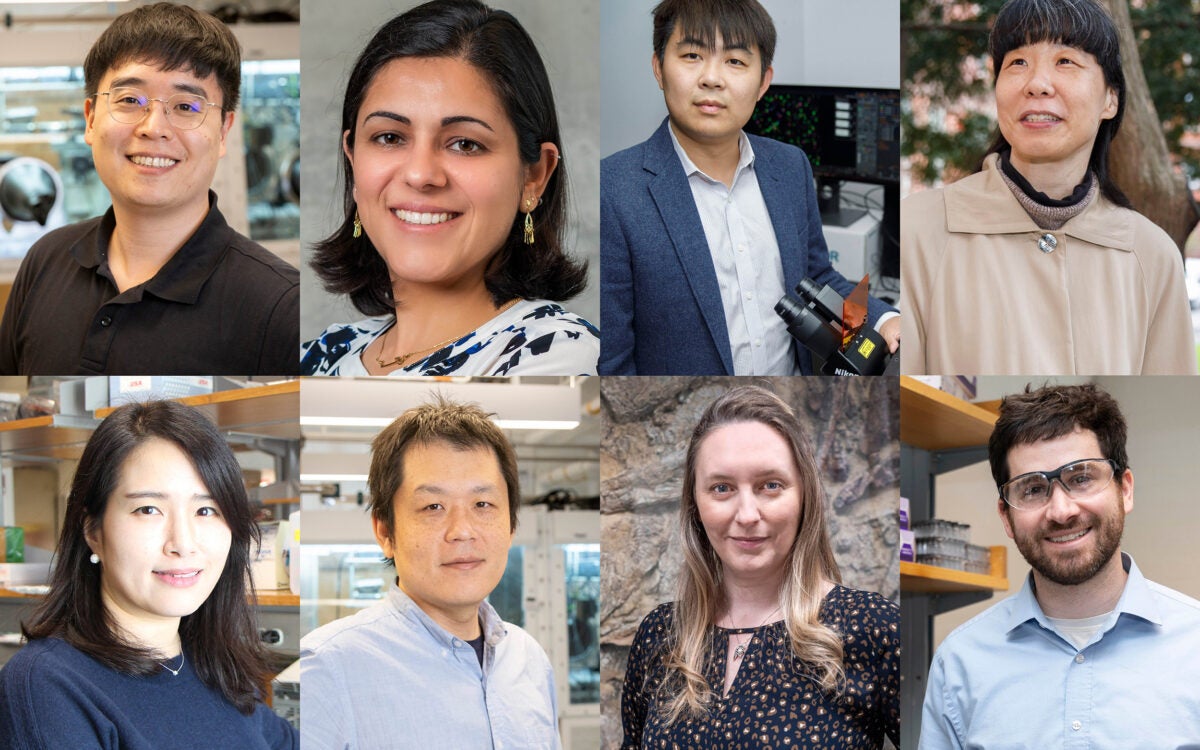

“Living With Flux,” by students Jing Guo and Meng Jia and instructor David Mah, imagines a resilient cityscape of “ecological sponge” that buffers saline tides and filters freshwater runoff.

Image courtesy of Chris Reed

Ideas to build on

Momentum at Harvard as design bends to rising seas

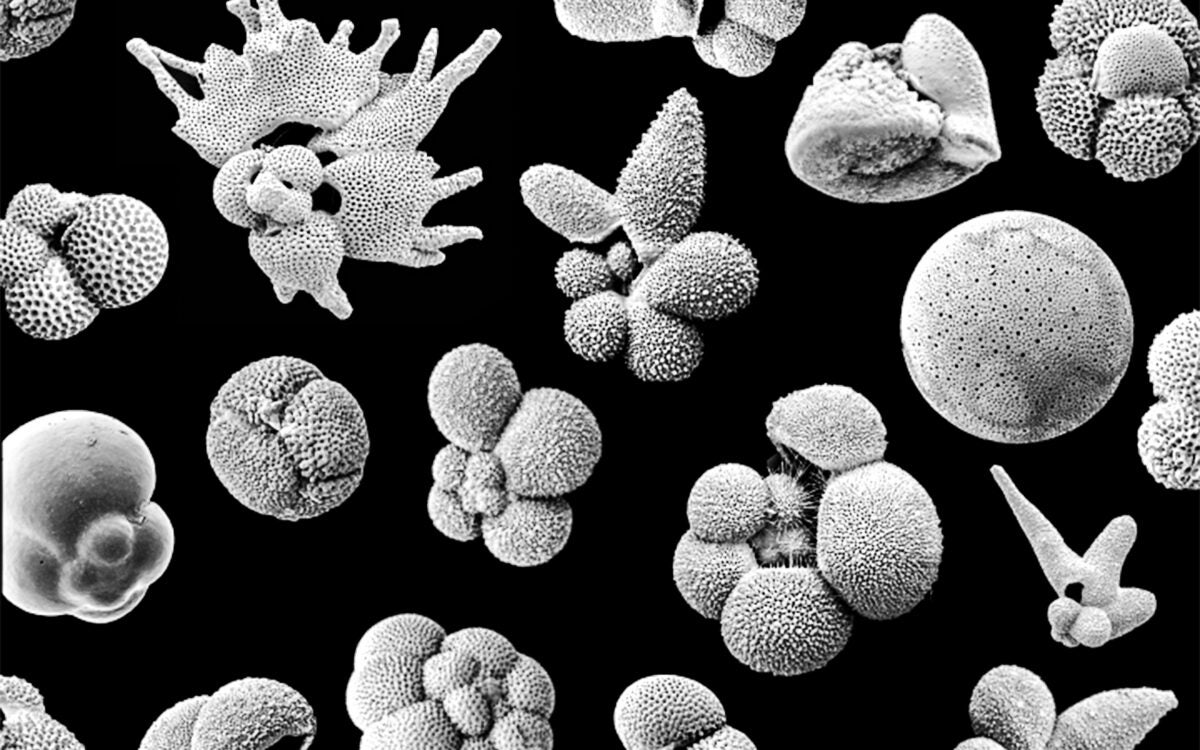

Earlier this year, landscape architecture students from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) did fieldwork in New York’s Jamaica Bay, a marshy estuary on the southwest coast of Long Island. Little more than a century ago, it was a wetland behind barrier beaches, an ecological feature that attenuated the waves and storm surges pulsing in from the ocean. Since then, dredging, fill operations, roadways, and industrial development have disturbed the sea-buffering ecology. How can designers help? The students — from a core spring studio called Flux City — were there to find out.

Just four months before the GSD students’ visit, Hurricane Sandy had punched into the bay, pushing a storm surge over beaches, roads, rail lines, and buildings. The evidence remained, including a swept-away car in a local creek.

Rising sea levels and their impact on coastal cities is “a hot topic,” said landscape architect Chris Reed ’91, a professor in practice of landscape architecture and founder of Boston-based Stoss Landscape Urbanism. Reed coordinates Flux City, eight credit hours of heavy lifting over 13 weeks that has been in place as a core requirement for a few years. Sea level rise was this year’s theme.

The studio and others like it are part of a movement reviving the idea that landscape architects represent a convening discipline for addressing complex urban issues. For a time, in the face of the ascendancy of engineering sciences, the directorial role of people such as Frederick Law Olmsted had segued into a lesser role for landscape architects. “Mostly at the garden scale,” said Reed. “We were brought in to dress up the problem, [to put] parsley in the pig.” But now large cities are again “turning to landscape architects to do big projects,” he said.

By 2050, with an expected maximum sea-level rise of 26 inches, Boston — itself an artifact of dig-and-fill operations going back centuries — could lose $460 billion in assets. That’s the cost of 20 Big Digs.

In the future, many of those big projects will no doubt concern rising sea levels, an issue that only now is getting the attention of North American cities. (In London, Rotterdam, Venice, and elsewhere it has been on the urban design agenda for decades.) In less than a century, by some estimates, sea levels could rise as much as 5 feet, penetrating coastal zones that include 136 port cities and 2 billion people — 37 percent of the world’s population.

Just this week, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that sea levels could rise more than 3 feet by 2100 if global-warming emissions stay on their current pace.

Especially vulnerable is the northeastern coast of the United States, including Baltimore, New York, and Boston. By 2050, with an expected maximum sea-level rise of 26 inches, Boston — itself an artifact of dig-and-fill operations going back centuries — could lose $460 billion in assets. That’s the cost of 20 Big Digs.

Related flooding in the world’s 136 coastal cities could cost $1 trillion a year, according to a study that appeared this week in the journal Nature Climate Change. Meanwhile, adapting to sea level rise could average $350 million per city per year, the study said.

Movement at Harvard

Harvard has engaged with the issue at its Schools of design, law, environmental science, public health, and public policy — though there is no official University forum or interest group yet.

At GSD, interested experts include Jerold S. Kayden, Charles Waldheim, Pierre Bélanger, and Spiro N. Pollalis of the Zofnass Program for Sustainable Infrastructure. Specialists at Harvard Law, the Kennedy School, and the Harvard University Center for the Environment are talking. Boston is awakening, too, and has hosted meetings on the problem over the last few years. This fall, the Boston Society of Architects will devote an issue of its quarterly magazine to the urban implications of rising seas.

As part of Flux City, the GSD students underwent an intensive orientation in drawing, model-making, theory, and the “full range of the options in play,” said Reed, including visits from experts in ecology, transportation, urban contaminants, and real estate. By the end, divided into teams of two, the students created 31 projects to address sea level rise, with Jamaica Bay as their ground zero. Nine are featured in a blog assembled by Reed and posted by the Architectural League of New York.

One project imagined a dynamic “super organism” of shifting dredge piles, breakwaters, moorings, and transient “building forms.” Another suggested making protective sea barriers from dredge material, along with new coastal forests of pine (on land) and kelp (at sea). A project titled “Float! Nautical Urbanism” called for a “buoyant city” of moored structures (including “chickees,” the lightest) that could be rearranged according to conditions. The only “grounded infrastructure” would be a system of boardwalks for hiking along tidal flats.

“Float!” was reminiscent of Makoko, an informal water settlement already underway in Lagos, Nigeria, described by architect Kunlé Adeyemi at a GSD lecture in March.

A middle way

Reed called the Flux City projects “speculative.” To date, many American responses to sea level rise have fallen into two camps: “Evacuate or build a bigger wall,” he said. “Maybe there are other ways.”

This middle way — not blocking, not retreating, but responding — represents what could be a transitional moment for landscape design, said Reed. “Stronger storms and seasonal inundation might actually suggest new forms of city life,” he wrote in the blog post. These forms would require “adaptability, resilience, and flexibility” instead of the classical urban imperatives of “stability, certainty, and order.”

Meanwhile, ecologically compromised areas like Jamaica Bay are “richly fluid territories,” he said: the best laboratories for finding ways to blend rigid built environments with the caprice of nature.

GSD professor and landscape ecologist Richard T.T. Forman posed the same idea in “Instigations: Engaging Architecture, Landscape, and the City” (2012), a collection of essays celebrating the School’s 75th anniversary. “Imagine the uneasy embrace of two giants, nature and the built world,” he wrote. “Shouldn’t we understand both?”

Reed mentioned another Flux City student project, which expresses the flexibility that future urban environments should have. “Living With Flux” imagines a sponge-like “soft landform” between city and sea, riven with pathways for filtering urban runoff and for buffering ocean water.

Still another would easily pay for itself, he said: alternating areas of elevated city and low-lying wetlands that would “triple or quadruple the shoreline, therefore raising the value of real estate.”

Money is an issue here, admitted Reed — but then again, “what makes good environmental sense may also make good economic sense.” These are, after all, “building projects that don’t get destroyed,” he said.

A greater challenge than money is governance, said Reed. Jamaica Bay, for example, has “a regional ecology but no single governmental entity.” A cross-jurisdictional patchwork is at play, from the City of New York, to the National Park Service (which has an office at Jamaica Bay), and authorities covering rail, highway, and airport facilities.

Then there is sentimentality, said Reed — the reluctance of those in the path of future storms to change or move. “The connections people have to a place sometimes overwhelm rationality.”

Ultimately, sea level rise is here and cities have to confront the implications, said Reed. All this year he has presented Flux City ideas in public forums, including the spring conference Waterproofing New York.

At Harvard, the next step “is to make more connections across the University,” said Reed. “Now’s the time.”