The study suggests that a low-glycemic load diet is more effective than conventional approaches at burning calories (and keeping energy expenditure) at a higher rate after weight loss.

Graphic courtesy of Boston Children’s Hospital

When a calorie is not just a calorie

Reducing refined carbs may help maintain weight loss better than reducing fat

A new study published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) challenges the notion that “a calorie is a calorie.”

The study, led by Harvard Medical School (HMS) Assistant Professor of Pediatrics Cara Ebbeling and Professor of Pediatrics David Ludwig, finds diets that reduce the surge in blood sugar after a meal — either low-glycemic index or very-low carbohydrate — may be preferable to a low-fat diet for those trying to achieve lasting weight loss. Furthermore, the study finds that the low-glycemic index diet had similar metabolic benefits to the very low-carb diet without negative effects of stress and inflammation as seen by participants consuming the very low-carb diet.

The research was conducted at the New Balance Foundation Obesity Prevention Center at Harvard-affiliated Boston Children’s Hospital, where Ludwig is director and Ebbeling is associate director.

Weight re-gain is often attributed to a decline in motivation or adherence to diet and exercise, but biology also plays an important role. After weight loss, the rate at which people burn calories (known as energy expenditure) decreases, reflecting slower metabolism. Lower energy expenditure adds to the difficulty of weight maintenance and helps explain why people tend to re-gain lost weight.

Prior research by Ebbeling and Ludwig has shown the advantages of a low-glycemic load diet for weight loss and diabetes prevention, but the effects of these diets during weight loss maintenance has not been well studied. Research shows that only one in six overweight people will maintain even 10 percent of their weight loss over the long term.

The study suggests that a low-glycemic load diet is more effective than conventional approaches at burning calories (and keeping energy expenditure) at a higher rate after weight loss. “We’ve found that, contrary to nutritional dogma, all calories are not created equal,” says Ludwig, who is also director of the Optimal Weight for Life Clinic at Boston Children’s Hospital. “Total calories burned plummeted by 300 calories on the low-fat diet compared to the low-carbohydrate diet, which would equal the number of calories typically burned in an hour of moderate-intensity physical activity,” he says.

Each of the study’s 21 adult participants (ages 18-40) first had to lose 10 to 15 percent of their body weight, and after weight stabilization, completed all three of the following diets in random order, each for four weeks at a time. The randomized crossover design allowed for rigorous observation of how each diet affected all participants, regardless of the order in which they were consumed:

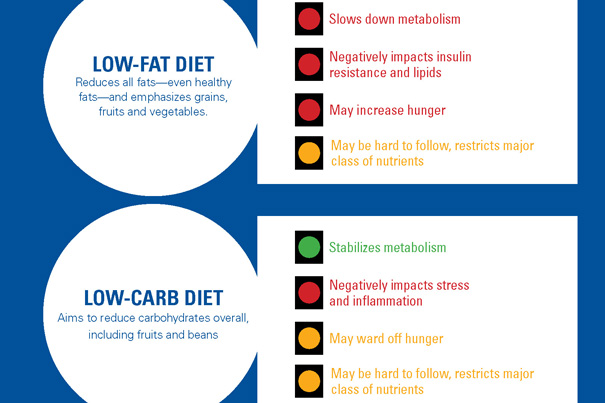

- The low-fat diet, which reduces dietary fat and emphasizes whole grain products and a variety of fruits and vegetables, was based on 60 percent of daily calories from carbohydrates, 20 percent from fat, and 20 percent from protein.

- The low-glycemic index diet, made up of minimally processed grains, vegetables, healthy fats, legumes and fruits, gathered 40 percent of daily calories from carbohydrates, 40 percent from fat, and 20 percent from protein. Low-glycemic index carbohydrates digest slowly, helping to keep blood sugar and hormones stable after the meal.

- The low-carbohydrate diet, modeled after the Atkins diet, was based on 10 percent of daily calories from carbohydrates, 60 percent from fat, and 30 percent from protein.

The study used state-of-the-art methods, such as stable isotopes to measure participants’ total energy expenditure, as they followed each diet.

Each of the three diets fell within the normal healthy range of 10 to 35 percent of daily calories from protein. The very-low-carbohydrate diet produced the greatest improvements in metabolism, but with an important caveat: This diet increased participants’ cortisol levels, which can lead to insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. The very-low-carbohydrate diet also raised C-reactive protein levels, which may also increase risk of cardiovascular disease.

Though a low-fat diet is traditionally recommended by the U.S. government and American Heart Association, it caused the greatest decrease in energy expenditure, an unhealthy lipid pattern, and insulin resistance.

“In addition to the benefits noted in this study, we believe that low-glycemic-index diets are easier to stick to on a day-to-day basis, compared to low-carb and low-fat diets, which many people find limiting,” says Ebbeling. “Unlike low-fat and very-low-carbohydrate diets, a low-glycemic-index diet doesn’t eliminate entire classes of food, likely making it easier to follow and more sustainable.”

Other co-authors of the study include Henry Feldman and Erica Garcia-Lago from Boston Children’s Hospital, Janis Swain from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, William Wong from Baylor College of Medicine, and David Hachey from Vanderbilt University. The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Center for Research Resources, the National Institutes of Health, and the New Balance Foundation.