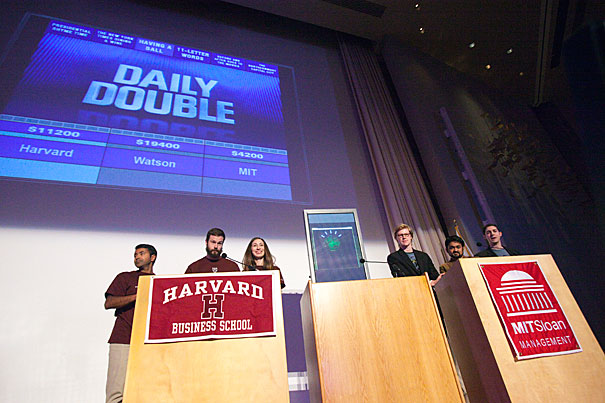

Harvard Business School and MIT Sloan students put IBM’s groundbreaking, “Jeopardy!”-winning computer to the test in a live match-up. But outsmarting Watson, it turns out, is a not-so-elementary task.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Students vs. computer

IBM’s Watson edges HBS, MIT players in ‘Jeopardy!’ match

Harvard Business School (HBS) and the MIT Sloan School of Management house some of the brightest up-and-coming minds in their fields. But on Monday, students from both schools came up against one super-brain they couldn’t best: Watson, IBM’s powerful computer.

HBS welcomed its new computer overlord — which “Jeopardy!” contestant Ken Jennings famously nicknamed Watson after conceding defeat on the show — on Halloween for a lively “Jeopardy!” match-up against teams of three from Harvard and Sloan. Before a crowd of hundreds, the two teams flanked Watson, represented by an unremarkable-looking computer monitor.

“We decided we were going to find the absolute best, cream-of-the-crop, top-of-the-barrel contestants we could possibly find,” said host Todd Alan Crain, so IBM turned to top universities.

But outsmarting Watson, the students learned, is a not-so-elementary task.

While MIT’s team finished the contest with a disappointing $100, HBS students Genevieve Sheehan ’05, Jonas Akins ’01, and Jayanth Iyengar came close to defeating Watson. When they momentarily took the lead late in the “Double Jeopardy!” round, the crowd roared.

In the end, however, IBM’s powerful computing tool bested Harvard. Both answered the “Final Jeopardy!” round correctly — Answer: “Finding the spot for this memorial caused its creator to say, ‘America will march along that skyline.’” Question: “What is Mt. Rushmore?” — but Watson bet just enough to ensure it would beat Harvard even if the HBS team bet its maximum.

HBS’s final total, $42,399, proved no match for Watson’s $53,601.

The game capped a daylong IBM symposium co-hosted by HBS and MIT. That morning, students, faculty, and representatives from IBM gathered at MIT for “The Race Against the Machine,” a series of talks on the current status and future potential of Watson and similar technology. After lunch, participants were bussed over to HBS’s Burden Hall for what IBM calls the “Watson Challenge.”

The conference also provided a learning opportunity for HBS students. Willy Shih, professor of management practice, wrote a case on Watson’s development for the required first-year MBA course “Technology and Operations Management,” which he taught for Monday’s class on innovation.

Setting the goal of taking Watson live on “Jeopardy!” was a bold but risky PR move, said Shih, who worked in product development at IBM for 14 years. But more than that, the decision to heighten the stakes for Watson’s performance created “this pressure to innovate,” Shih added. “The public pressure — coupled with a very simple goal [of] winning at ‘Jeopardy!’ — instantiated a whole bunch of scientific research and … motivated the team to step up the pace and really aggressively go after the target.”

The takeaway for M.B.A. students, he said, is that “all of these things together become an important component for driving innovation.”

The game also offered an insight into the technology behind Watson. Watson is more than just a headline-grabbing party trick. It’s actually a demonstration of IBM’s innovative DeepQA software, a product in development since 2007. IBM hopes DeepQA will transform fields like health care that require human practitioners to access a huge pool of knowledge to make decisions.

David Ferrucci, an IBM fellow and the principal investigator on the DeepQA project, said the IBM team set out to explore the differences between how a human and computer might process something so inherently human as language.

“It’s not the word or the phrase itself that contains knowledge; it’s reference to a common experience that enables us to communicate,” Ferrucci told the audience.

To play “Jeopardy!” Watson generates many hypotheses as to what a question is asking, collects a wide range of evidence from available sources (Wikipedia, for instance), and balances the combined confidences of more than 100 algorithms that analyze that evidence, Ferrucci said. To do that process in mere seconds, rather than over the course of hours, Watson requires 15 terabytes of memory.

“When you think about what it meant for this machine to play against a human in ‘Jeopardy!’ you sort of have to appreciate that here’s a human brain that fits in a shoebox, powered by a sandwich and a glass of water, and in the other room is 10 racks of [servers],” Ferrucci said.

The anthropomorphized, commercially available technology (it’s not a supercomputer, IBM stressed) offers “a foundationally new way of augmenting your capabilities,” said Bernard Meyerson, an IBM fellow and the company’s vice president for innovation.

“What would you do if you had a genius who sat by your side, never had a bad day, forgot nothing, and could give you a level of assistance you’d never even dreamed of 24/7 without being aggravated?” Meyerson asked the crowd. “It’s not the future. It is now.”

Indeed, the HBS team learned firsthand just how unnerving Watson’s unerringly steady performance could be.

“With a human competitor, there’s a lot more factors you’ve got to think about,” Iyengar said. “What’s their background? What might they know or not know? There’s a lot more strategy involved. Here you could select any category, and Watson would have the same kind of computing power potentially to be able to solve it.”

Watson also elicits a different emotional reaction in players, said Sheehan. She and Iyengar would know. Both have appeared on “Jeopardy!” before. Sheehan came in third in her 2009 performance, while Iyengar made it to the finals in “College Jeopardy!” in 2005.

“If your [human] competitor does better than you, you think, ‘Oh, they’re a good competitor, they’re getting strong, I can beat them,’” Sheehan said. “When a computer does better than you, you kind of feel like you’re being cheated.

“When we gained momentum at the end of the match, we really felt like we were in control of the game, especially against MIT,” Sheehan said. “But you know that Watson as a computer isn’t reacting to that.”

Still, the HBS team couldn’t help but smile after the match ended, even teasingly referring to themselves as “human champions” in front of their MIT counterparts.

“We put on a strong challenge and came so close to winning,” Sheehan said. “I feel as if we won.”