De-identified prescription data: Is it really anonymous? Latanya Sweeney aims to make personal data more secure and to provide recourse for people who are harmed by privacy breaches.

Photo courtesy of Flickr user Dan Buczynski

You’re not so anonymous

Medical data sold to analytics firms might be used to track identities

When you visit a pharmacy to pick up antidepressants, cholesterol medication, or birth control pills, you might expect a certain measure of privacy. In reality, prescription information is routinely sold to analytics companies for use in research and pharmaceutical marketing.

That information might include your doctor’s name and address, your diagnosis, the name and dose of your prescription, the time and place where you picked it up, your age and gender, and an encoded version of your name.

Under federal privacy law, this data sharing is perfectly legal. As a safeguard, part of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requires that a person “with appropriate knowledge of and experience with generally accepted statistical and scientific principles and methods” must certify that there is a “very small” risk of re-identification by an “anticipated recipient” of the data.

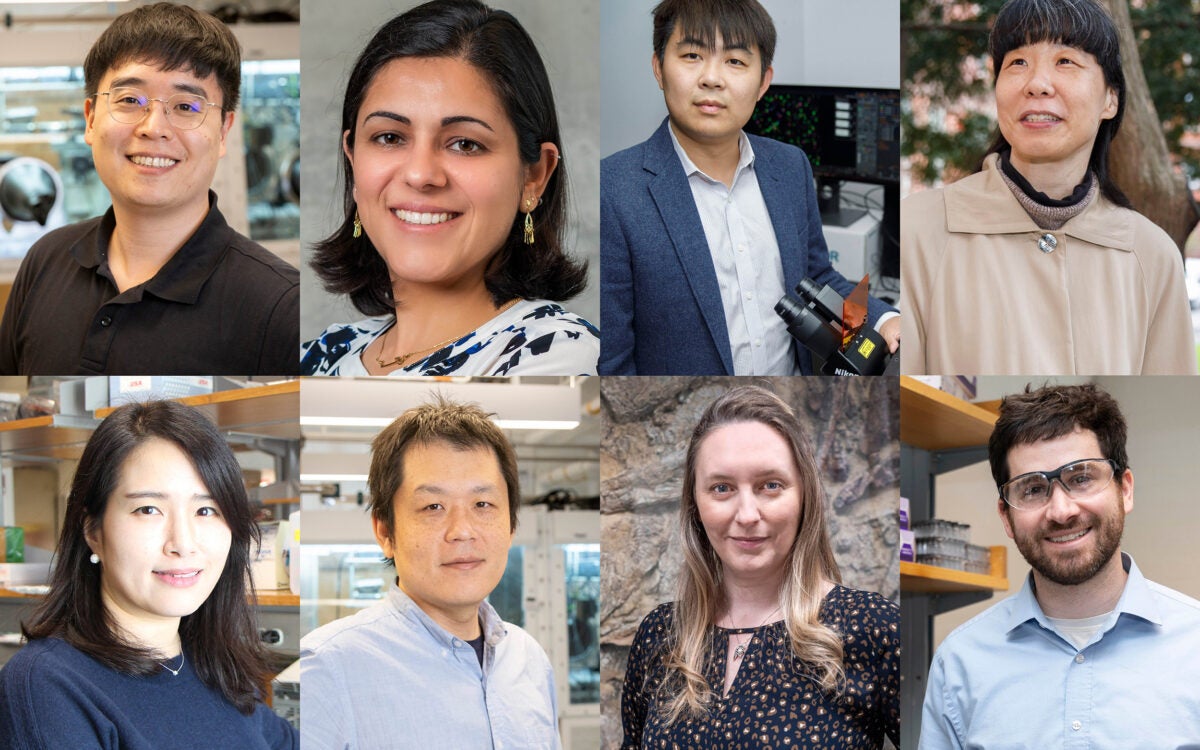

But Latanya Sweeney, A.L.B. ’95, a visiting professor of computer science at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), warns that loopholes abound. Even without the patients’ names, she says, it may be quite easy to re-identify the subjects.

Sweeney suspects this to be the case because she is an authority on matching “anonymous” data with other public records, exposing security flaws. Keeping data private, she insists, involves far more than just the removal of a name — and she’s eager to prove that, with a quantitative, computational approach to privacy.

In 2000, Sweeney analyzed data from the 1990 census and revealed that, surprisingly, 87 percent of the U.S. population could be identified by just a ZIP code, date of birth, and gender. Given the richness of the secondary health data sold by pharmacies and analytics companies, she says, it should be quite easy to determine patient names and strike upon a treasure trove of personal medical information.

Not that she’s particularly interested in whether you’re taking Lipitor or Crestor.

Instead, Sweeney, the founder and director of Harvard’s Data Privacy Lab, aims to expose the weaknesses in existing privacy laws and security mechanisms in order to improve them. By challenging outdated policies, she hopes to demonstrate that stronger, more complex algorithmic solutions are necessary to protect sensitive data effectively.

A computer scientist at heart, Sweeney has teamed up with colleagues at the Center for Research on Computation and Society at SEAS, investigating a range of new economic models for data sharing and protection.

With SEAS faculty members David Parkes, the Gordon McKay Professor of Computer Science, and Stephen Chong, assistant professor of computer science, as well as Alex Pentland at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sweeney advocates a “privacy-preserving marketplace” in which society can reap the benefits of shared data, especially in the scientific and medical arenas, while also protecting individuals from economic harm when the data is shared beyond its original intended use.

“We don’t want data to be locked away and never used, because we could be doing so much more if people were able to share data in a way that’s trustworthy and aligned with the intentions of all the participants,” said Parkes.

Medical, genetic, financial, and location data, along with purchasing histories, are all extremely valuable pieces of information for social science research, epidemiology, strategic marketing, and other behind-the-scenes industries. But if one database can be matched up with another — and, as Sweeney has demonstrated, it often can — then an interested party can easily generate a detailed picture of a specific individual’s life.

This can be both useful and damaging, as when participants in a genomic study help advance science but then find themselves unable to obtain life insurance.

Other harms are easy to imagine, said Sweeney.

“They might know that they have cancer and all of a sudden their credit card debt is going crazy. Or they may not get that promotion at work. Or they may get fired because all of a sudden now little Johnny has this very expensive heart disease, and they’re a big liability.”

After-the-fact protections for some of these types of discrimination do exist, but mechanisms to compensate for these harms fairly — or to prevent them entirely — are weak.

Sweeney, Parkes, Chong, and Pentland theorize in a working paper that if one were able to quantify the risk of leaky data accurately, a privacy-preserving marketplace could compensate participants at a level according to that risk. In other words, if the public puts aside the expectation of 100 percent anonymity and security, a more trustworthy system might take its place.

As it happens, techniques in computer science and statistics (such as differential privacy, a specialty of Salil Vadhan and others at Harvard) do allow for quantifying the risk of harm.

A remaining question, then, is whether the average individual is capable of understanding a 4 percent risk versus a 14 percent risk and acting rationally upon it.

“The role of privacy policy, in a system where individuals are going to exercise autonomy, is to make sure they don’t shoot themselves in the foot,” said Sweeney.

“One experiment after another has shown that people will make poor decisions about anything that involves their privacy. They want the new utility, they want the new shiny thing, because we tend to discount that any harm is going to happen to us, even when we’re told that it could.”

Sweeney and her colleagues suggest a marketplace where computational and cryptographic techniques guarantee a certain measure of privacy, where subjects are compensated according to the level of risk they incur by participating, and where government policy backs up the system — perhaps by mandating insurance against major losses.

“Generally, the problem with policy is that it can’t be very nuanced,” said Parkes. “But maybe you can use policy to regulate the way marketplaces work, and then let the market solve the optimization problem.”

Most federal privacy regulations, which Sweeney calls “sledgehammer” policies because of their lack of finesse, were written in an era without digital records, without the Internet, and without fast computers.

Data that is only weakly anonymous did not pose much of a threat 30 years ago. No one was likely to pore through millions of records by hand to find patterns and anomalies. Now, everything has changed, said Sweeney, “right in the middle of a scientific explosion in both social science data and genomic data, and these kinds of notions from HIPAA and 1970s policies are an ill fit for today’s world of what we might call ‘big data,’ where so many details about us are captured.”

For example, she said, the “fair information practices” spelled out in the 1974 Privacy Act allow you to view your records and challenge the content, but you don’t get to decide who can report them or who else gets to see them. The hospital makes you sign to affirm that you’re aware of the institution’s data-sharing policy, but you can’t really opt out of it if you want medical treatment. And while data released by entities covered by HIPAA are required to delete identities, Sweeney says the standards for anonymity are too vague.

A vocal advocate of change at the national level, Sweeney backs up her assertions with real technological solutions, including original software that identifies risks in data sets. And the authorities are listening. In 2009 she was appointed to the privacy and security seat of the federal Health Information Technology Policy Committee, and this year her work was cited in a high-profile U.S. Supreme Court case.

“She has a very deep knowledge in policy issues and is developing a very interesting network of people in industry who are able to advise her agenda and inform it,” said Parkes. “I think Latanya, much more than everybody else in this space, is able to figure out the really important questions to ask because of that network and the expertise she’s built up over the years.”

Can this network of computer scientists, policy experts, privacy advocates, and corporations produce a system that simultaneously allows the productive sharing of data while guaranteeing some degree of privacy?

“Right now we’re seeing lawsuits, and they’re giving a blunt response to these questions,” said Parkes.

Unless lawmakers and institutions thoroughly rethink privacy protections, Sweeney warned, “either we’re going to have no privacy because they’re ineffective, or we’re going to lose a tremendous resource that these data have the potential to provide.”

To learn more about Sweeney’s work on rethinking privacy and preserving it in the marketplace, watch this taped lecture from the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard.