‘Spiritual’ color featured in show on painter Delaney

“Beauford Delaney: The Color Yellow,” an exhibit of 26 paintings by the African-American artist, will be on view from Feb. 15 through May 4 at Harvard’s Sert Gallery in the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. From the portraits and cityscapes he did in New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1940s, to the abstract work that followed his move to Paris in 1953, the exhibit presents the full range of Delaney’s art. The first retrospective of his work in 25 years, the exhibit was organized by Atlanta’s High Museum of Art with support for the national tour provided by MetLife Foundation.

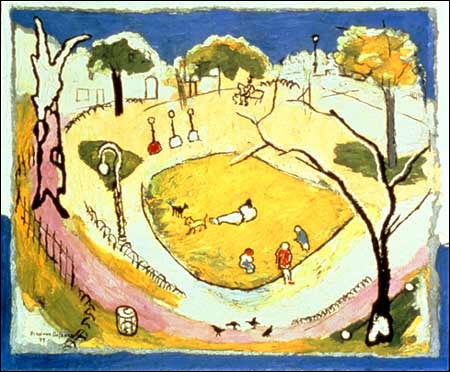

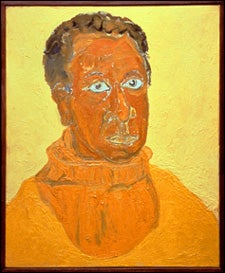

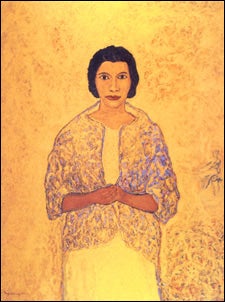

The exhibition – and its accompanying catalog – are the first to explore this artist’s use of the color yellow, which he employed as a pivotal symbolic and expressive element in both his figurative and abstract works. Delaney believed that the various hues held spiritual significance and that the color yellow represented light, healing, and redemption.

“The exhibition ‘Beauford Delaney: The Color Yellow’ is a wonderful demonstration of the Art Museums’ desire to provide a meaningful, scholarly, and diverse experience for all our visitors,” said Marjorie Cohn, acting director of the Harvard University Art Museums (HUAM). “Through exhibitions organized by colleagues elsewhere, we fill gaps in our collections, so that the community becomes acquainted with important yet less familiar artists.”

“Jazz and literature were lasting sources of inspiration for the artist,” said Harry Cooper, associate curator of modern art at the Fogg Art Museum. “Delaney’s portraits of Ella Fitzgerald, whose music captivated him in New York, and James Baldwin, whose close friendship eased Delaney’s later years, are examples of his motivation to create art in spite of poverty and mental illness. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of his career is that while continuing to do portraits, he created a parallel body of thickly brushed radiantly abstract paintings.”

A native of Knoxville, Tenn., Delaney took lessons from a local artist before moving to Boston in 1924 to begin his formal training at several area schools, including the Massachusetts Normal Art School and the Copley Society. He moved in 1929 to New York City and immersed himself in the lively bohemian scene of Greenwich Village. It was Delaey’s pastel portraits of ordinary people as well as notables like Duke Ellington and Marian Anderson that won the artist public acclaim and numerous exhibitions. For the remainder of the 1930s and ’40s, Delaney was well known in the New York art world for his bold and experimental use of color. His art reflected both the black culture flowering around him and the message of French modernism, which he received through friends and mentors like the painter Stuart Davis and the photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

In 1953, Delaney traveled to Paris, fleeing racism in the United States and making the city his home for the remainder of his life. He joined a community of artists and writers in that city that included Baldwin, Henry Miller, Sam Francis, and Bob Thompson. Delaney increasingly moved away from figuration to explore the emotional power of abstraction, producing an extensive body of work in watercolor and oil on canvas. Plagued in the 1960s and ’70s by schizophrenia and alcoholism, Delaney was frequently hospitalized, reducing his output although his paintings were featured in many exhibitions in the United States and Europe. Delaney died in 1979 one year after a first retrospective of his work at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

About Delaney, Baldwin said: “He has been starving and working all of his life – in Tennessee, in Boston, in New York, and now in Paris. He has been menaced more than any other man I know by his social circumstances and also by all the emotional and psychological stratagems he has been forced to use to survive; and more than any other man I know, he has transcended both the inner and the outer darkness.”

The exhibition has already appeared at the High Museum of Art; the Studio Museum in Harlem; and the Anacostia Museum and Center for African History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. The Fogg is the final venue on the exhibition’s national tour. Additional funding for this presentation was provided by the Judith Rothschild Foundation.