Stolen Lives: Trafficking of women

‘The first thing they lose is their freedom. Then they’re subjected to violence to make them submit.’

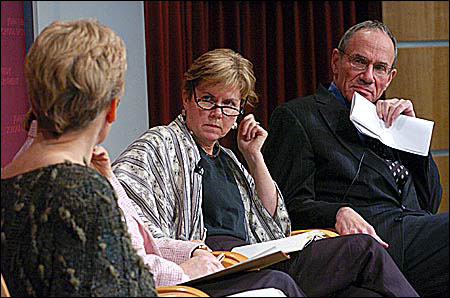

Gathering for what moderator Swanee Hunt, director of the Women and Public Policy Program, called a “grim subject,” a group of experts met in the Kennedy School Forum to talk about the trafficking of women and girls worldwide and what, if anything, can be done to stop it.

“Our estimates show that about 800,000 women and children are trafficked across borders every year, and this number doesn’t include internal trafficking,” said John Miller, director of the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons at the U.S. Department of State. “It ranges from sex slavery to farm slavery – you name it. This comes as a shock to many people who think: Didn’t slavery end with the Civil War?”

Asked why we should care about the issue, Miller responded, “It’s an affront to human dignity, for starters. There’s also the public health toll, particularly with HIV and AIDS in the sex slavery business.”

There’s also the loss and brutality experienced by the women and girls lured or tricked into sex jobs, said Donna Hughes, chair of the Women Studies Program at the University of Rhode Island.

“The first thing they lose is their freedom. Then they’re subjected to all forms of violence to make them submit,” she said. “Because of the physical and psychological trauma, for many victims, the only recourse is suicide.”

Hughes said another cost to a society where trafficking occurs – and the panelists were quick to note that it exists in almost every country, including the United States – is a compromised rule of law.

“In order for trafficking to succeed, there’s corruption. Some official from the government or the police is involved,” she said. “And when the rule of law is compromised, all of society suffers.”

Panelist Jane Holl Lute, assistant secretary-general for peacekeeping operations at the United Nations, spoke about a different – but closely related – topic, one that received widespread attention last year: the sexual exploitation and rape of women and girls by UN peacekeepers.

“In the past, the attitude on this has been, ‘boys will be boys,’” she said. “But someone who rapes is not a boy. Someone who exploits women is not a boy. There’s a word for these kinds of people, but ‘boy’ is not it.”

Asked why it took the UN so long to respond, Holl Lute shook her head in frustration and said, “The UN will have to account for why it has taken so long to deal with this problem. But words are not enough.”

Addressing a question about how to confront the exploitation of women and girls, Hughes said that putting pressure on politicians was critical. Miller added that educating people in villages was also necessary, as was targeting rich countries, like the United States and Japan, which fuel the sex tourism industry. Other suggestions included sensitizing local police to the issues and, in response to the problems experienced at the UN, making training mandatory for peacekeepers.

Lastly, said Hughes, is for everyone to look around, no matter where they are.

“Think globally, but act locally,” she said. “You don’t have to go into the Congo or Nepal. The problem is right here.”