Illustration by Nick Shepherd/Ikon Images

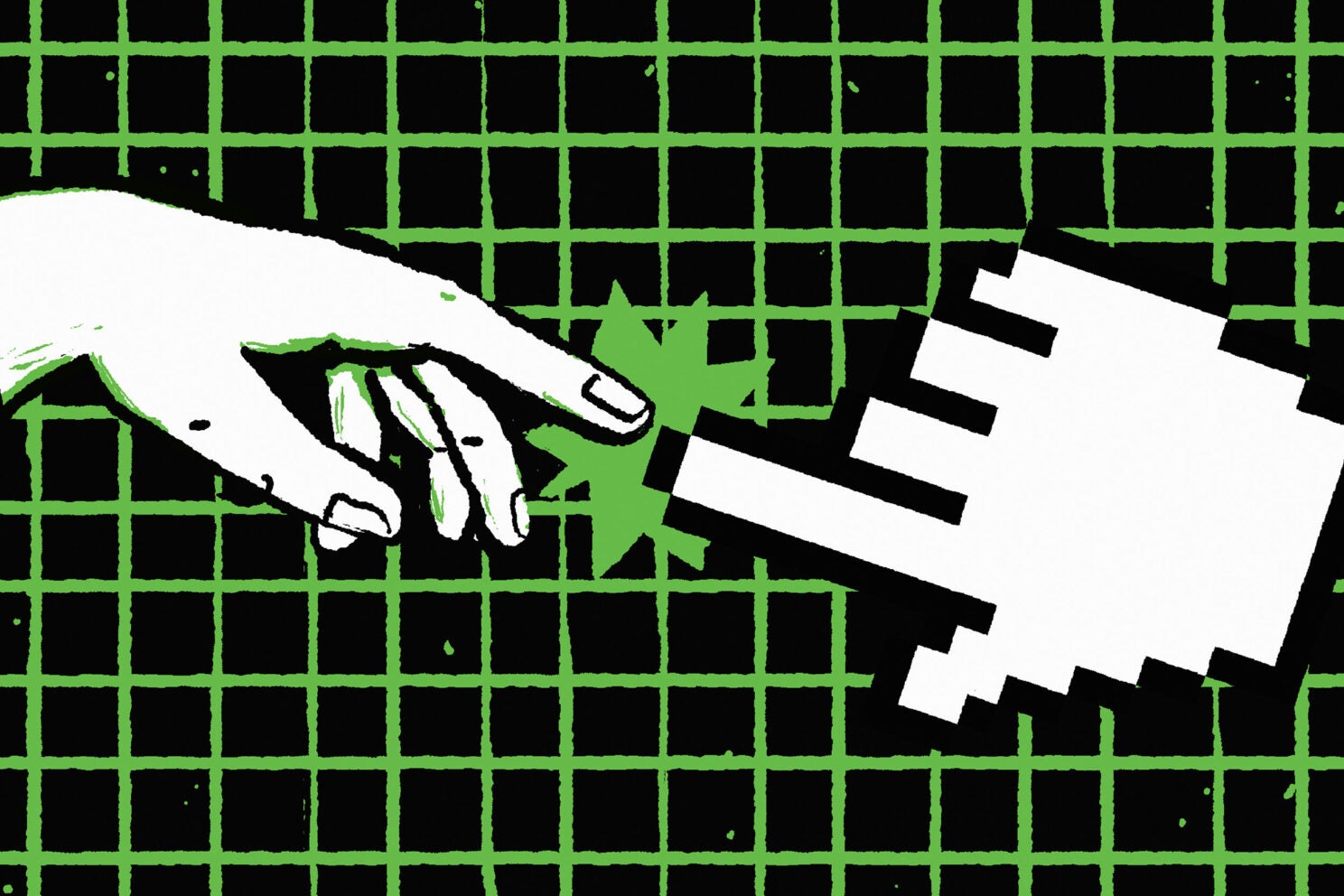

‘Harvard Thinking’: Is AI friend or foe? Wrong question.

In podcast, a lawyer, computer scientist, and statistician debate ethics of artificial intelligence

ChatGPT’s launch in late 2022 heightened the debate about whether recent leaps in artificial intelligence technology will help or hurt humanity — with some experts warning that AI tools pose an existential threat and others predicting a new era of flourishing.

Perhaps we need a bit more nuance in the conversation, argues Sheila Jasanoff, a science and technology expert at Harvard Kennedy School.

“I’ve been struck, as somebody who’s been studying risk for decades and decades, at how inexplicit this idea of threat is,” Jasanoff said in this episode of “Harvard Thinking.” “There’s a disconnect between the kind of talk we hear about threat and the kind of specificity we hear about the promises. And I think that one of the things that troubles me is that imbalance in the imagination.”

Martin Wattenberg, a computer scientist at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, said he’s been surprised at some of the ways AI has developed. While Hollywood depictions tend to depict enormous advances in math and science leading to humanity’s demise, what we’ve seen is a rise in creative augmentation through programs like Midjourney and DALL·E.

“In some ways it feels like the cutting edge [of AI] is with astonishing visuals, with humor even, with things that seem almost literary,” he said. “That’s been really surprising for a lot of people.”

Regardless of how AI continues to develop, ethics need to be at the forefront of conversations and integrated into education, said Susan Murphy, a statistician and associate faculty member at the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence. One model of how that might be done is Harvard’s Embedded EthiCS initiative to weave philosophy and ethical modules into computer science coursework.

“We all have a responsibility to ensure our research is used ethically,” she said. “Often we go off the trail when someone has an enormous amount of hubris … and then there’s all these unintended consequences.”

In this episode, host Samantha Laine Perfas, Jasanoff, Wattenberg, and Murphy discuss the perils and promise of AI.

Transcript

Sheila Jasanoff: So with AI, there are going to be consequences, and some of them will be good surprises, and others of them will be bad surprises. What is it that we want to do in the way of achieving a good society and where does the technology help us or hurt us?

Samantha Laine Perfas: Until recently, the capabilities of artificial intelligence have fallen short of human imagination. It’s now catching up, and it raises the question: How do we develop these technologies ethically?

Welcome to “Harvard Thinking,” a podcast where the life of the mind meets everyday life. Today we’re joined by:

Martin Wattenberg: Martin Wattenberg. I’m a computer scientist and a professor here at Harvard.

Laine Perfas: Martin is also part of Embedded EthiCS, a Harvard initiative to bring philosophers into computer science classrooms. Then:

Susan Murphy: Susan Murphy. I’m a professor also here at Harvard. I’m in statistics and the computer science department.

Laine Perfas: She’s also a faculty member at the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence. She works at the intersection of AI and health. And finally:

Jasanoff: Sheila Jasanoff. I work at the Kennedy School of Government.

Laine Perfas: A pioneer in the field, she’s done a lot of work in science policy. Lately, a major topic of interest has been the governance of new and emerging technologies.

And I’m your host, Samantha Laine Perfas. I’m also a writer for The Harvard Gazette. And today we’ll be talking about the peril and promise of AI.

Artificial intelligence has been in the news a lot over the last year or so. And a lot of the coverage I see focuses on why we should fear it. What is it that is so scary about AI?

Jasanoff: I’ve been struck, as somebody who’s been studying risk for decades and decades, at how inexplicit this idea of threat is. Whether you look at the media or whether you look at fictive accounts or whatever, there is this coupling of the idea of extinction together with AI, but very little specificity about the pathways by which the extinction is going to happen. I mean, are people imagining that somehow the AIs will take control over nuclear arsenals? Or are they imagining that they will displace the human capacity to think, and therefore build in our own demise into ourselves? I mean, there’s a disconnect between the kind of talk we hear about threat and the kind of specificity we hear about the promises. And I think that one of the things that troubles me is that imbalance in the imagination.

Wattenberg: For me, the primary emotion and thinking about AI is just tremendous uncertainty about what’s going to happen. It feels almost parallel to the situation when people were first effectively using steam engines a couple hundred years ago, and there were immediate threats. In fact, a lot of the early steam engines literally would blow up. And that was a major safety issue. And people really worried about that. But if you think about the industrial revolution over time, there were a whole lot of other things that were very dangerous that happened, ranging from terrible things happening to workers and working conditions, to nuclear weapons, to the ozone layer starting to disappear, that I think would have been very hard to anticipate. One of the things that I feel like is a theme and what has worked well is very close observation. And so my feeling at this point is that, yeah, there is a lot of generalized worry that in fact, when there’s any very large change, there’s all sorts of ways that it can potentially go wrong. We may not be able to anticipate exactly what they are, but that doesn’t mean we should just be nihilistic about it. Instead, I think we should go into very deliberate, active information-gathering mode in a couple of ways.

Jasanoff: Martin, I think that’s an excellent entry point to get serious conversation going between us over at the Kennedy School and people in public health and other places, because it raises the question of whose responsibility is it to do that monitoring? I’m an environmental lawyer by training. I got into the field before Harvard was even teaching the subject. And one of the things that we chronically do not do as a society is invest in the monitoring, in the close supervision that you’re talking about. Time after time, we get seduced by the innovative spirit. I think that on the whole, the promise discourse tends to drown out the fear discourse, at least in America. I mean, it’s often considered part of what makes America great, right? That we are a nation of risk-takers. But it does raise the question, whether we’re willing to invest in the brakes at the same time that we’re investing in the accelerator. And this is where history suggests that we just don’t do it. Brakes are not as exciting as accelerators.

Laine Perfas: As someone who is not a computer scientist and not as well-versed in the nitty-gritty of artificial intelligence, I think a lot of the conversations that I hear or read or see seem so binary. I appreciate hearing some of the more nuanced ways that you all are thinking about this. And I’m curious if there’s other nuance that needs to be in this conversation.

Jasanoff: I think some of the nuance has to be around the whole idea of intelligence, right? People who are dealing with education theory, for instance, have been pointing out for a long time that one of the great faculties of the human mind is that we’re intelligent about very different things. I know people who are fantastic at math and have low, you know, emotional maturity and intelligence. And I know people who have no sense of direction, but still can compose music. And there has been a discussion about how the computer and also the personalities who do computer science may be guiding that idea of intelligence in overly narrowing ways.

Wattenberg: A lot of times you do hear questions about to what degree the people who are working on AI, that composition of this group, “Is that affecting what is happening, and in particular, the type of technologies developed?” And I think in many ways, you can point to aspects where there is an effect. But I would also say that collectively as a field, I think we are very interested in other approaches. I think there would be actually tremendous appetite for collaboration. There is another thing that I would say, which is that it’s not just the people, though. The technology itself has certain affordances of what turns out to be easy, what turns out to be really expensive to do, and that ends up being part of the equation as well. I think it’s important to take into account both the human aspect and how various human biases are coming into play, but also realize that to some extent, there are technical things happening. Some things just have turned out to be much easier than people expected. And some things have turned out to be harder. I would say the classic example of this that people talk about informally is that if you look at Hollywood depictions of AI, say Data from “Star Trek,” where people expected that the first big breakthroughs would be very mathematical, very literal. Instead, when we look at large language models, or, say, generative image models like DALL·E or Midjourney, in some ways it feels like the cutting edge is with astonishing visuals, with humor even, with things that seem almost literary in certain ways. And I think that’s been really surprising for a lot of people.

Murphy: I just wanted to jump in and, it’s a little bit of a different direction, but in terms of all of us who work at AI, we all have a responsibility to ensure our research is used ethically. The CS (Computer Science) department at Harvard is really trying hard to embed ethics in the classes. And I feel that’s a critical point because often we go off the trail when someone has an enormous amount of hubris and they think they don’t need anyone else and they can just do something, and then there’s all these unintended consequences. Whereas this Embedded EthiCS course, Martin, can you speak a little bit? I really feel like this is a bright point.

Wattenberg: Yeah. The general idea is that you want to make sure that students understand that ethics is just part of how you think about things in general, and so as part of many courses in the computer science departments, there’ll be a module that’s embedded, this is done with the philosophy department, to think about the very complicated issues that come up. There really is this sense that it is part of what we need to think about.

Jasanoff: There are two points I’d like to make in this connection. Many years ago, I was in a discussion when nanotechnology was the newest kid on the block, and all of humanity’s problems would be solved by going nano. There is this element of hype around new technologies. But people were talking about nano ethics. And a skeptical voice in the room said, “Well, there’s a lot of imitation going on here, because bioethics is a field and nanoethics is building on that.” This person said, “Does anybody know of a single case where bioethics said, stop, do not continue this line of research”? And there was dead silence in the room. And that fits with a perception that as soon as you turn ethics into a set of modularized principles, you end up standardizing the moral faculties in some ways. With bioethics, where, after all, we have now 30-plus years of experience with packaged or principalist bioethics, as people call it, people have turned away from that and have said that in order to really grapple with the moral dilemmas around such things as how much should we intervene in human reproduction, for instance, the philosophy department is not the right place to start. I don’t want to be a party spoiler in a sense, but there is a whole debate about what we’re trying to accomplish by thinking about ethics as a kind of add-on to the process instead of, let’s say, starting with the moral questions. What is it that we want to do in the way of achieving a good society? And where does the technology help us or hurt us? As opposed to starting with the technology and saying, “This is what the technology can do. Now imagine ethically problematic consequences.”

Murphy: I think I operated at a much lower level. For example, we have these algorithms, they’re running online, and they’re with people that are really struggling with some sort of health condition. And we’re thinking, “How are we going to monitor these algorithms as they learn about the individual and provide different kinds of suggestions or nudges?” And our main red flag is ethics. Are we overburdening these people? Are we causing trouble in their lives? It’s just, it’s all very practical. The algorithm we’re designing is all about the patient comes first, research is second.

Laine Perfas: I’m also curious if pursuing ethics is a challenge because not everyone is on board with using technology ethically. A lot of times technologies are used for malicious purposes or for personal gain. I’m wondering as artificial intelligence continues to develop so quickly, beyond just ethics, how do we also create space for things like regulation and oversight?

Jasanoff: I would take issue with the idea that ethics can be separated from regulation and oversight, because, after all, regulation and oversight express a population’s collective values. Regulation is a profoundly ethical act. It says that there are certain places we should go and certain places that we should not go. You know, I think that we haven’t put the question of money into this discussion. I mean, there’s this idea that the technology is just advancing by itself. It’s not just the brilliant engineer who has got nothing but the welfare of the patient in mind. It’s also, what are the spinoff technologies? Who’s going to come forward with the venture capital? Whose preferences, whose anticipatory ideas get picked up and promoted? Where is that discussion going to be had? Susan, I’m absolutely in sympathy with you. I don’t think it’s low-level at all, and I think in fact calling it low-level, the sort of pragmatic, on-the-ground thing, is disabling what is a noble instinct. I mean, that’s part of the Hippocratic Oath. If we’re going to deliver a medical service, we should do it for the benefit of the patient, right? I don’t think that’s low-level at all, but it is kind of linear. That is, when we say that it shouldn’t nudge the patient in the wrong direction. But supposing our problem is obesity, which is a big problem in this country. Should we be tackling at the level of nudging the patient into more healthful eating, or should we also be discussing how Lunchables get into the lunchbox?

Murphy: Right on with influence of money, Sheila. At least in my world, you put your finger right on a big concern. There’s very strong monetary incentives to go in certain directions, and it’s hard to fight against that.

Wattenberg: Yeah, I think that this idea of what is equitable and what isn’t, this is absolutely critical. When we talk about what are the worries with AI, this is one that you hear people talk about a lot: What if it ends up helping the already powerful become even more powerful? Now, I will say that those to me seem like incredibly legitimate worries. They also do not seem like inevitabilities to me. I think there are many paths to making sure that technology can work for many people. There’s another thing that I think is actually potentially very interesting; some of these technologies, so ChatGPT, for example, may help less-skilled people more than highly skilled people. There’s an interesting study that came out recently where people were thinking of ideas in a business setting. And what they found is that the most skilled people who were tested weren’t improved that much by using ChatGPT, but the performance was very much improved by people who were less skilled. And that’s interesting because it’s sort of flattening a curve in a way. Now, whether that study holds up I don’t know. But it’s an interesting thought, you know, I think that we should not assume that it is going to increase inequality and in fact what we should try to do is work very hard so it does not.

Jasanoff: Martin, if I could throw the question back at you: But supposing what it means is that the less-skilled jobs can be replaced by a ChatGPT, but the higher-skilled jobs cannot? Then is that not a different sort of take on the problem that routinized tasks would be better performed by mechanical instruments whose job it is to do routine? That’s relatively easy to appreciate as just a logical point. Since you referred to the history of technology, we’ve seen when machine looms were first introduced, they displaced the people at the lower end of the scale. So what has happened over hundreds of years? We still appreciate the craft skills, but now it’s the very rich people who can afford the craft. Hand-loomed silk fabrics and hand-embroidered seed pearls still command unbelievable prices. It’s just that, most people can only afford glass pearls or whatever. And we are certainly in a much more technologically interesting world, there’s no doubt about it. But the inequality problems, if anything, are worse. That is a kind of problem that does preoccupy us on our side of the river.

Wattenberg: I think there’s this broad question about technology in general, and then there’s, I think, the specific question about what is different about AI. This I think we don’t know yet. And, to go back to what you began with in terms of will this lead to job displacement, there is this famous saying that the worries about AI are all ultimately worries about capitalism. And I think it’s a fairly deep saying in a lot of ways. But even within the framework that we have, could we reconfigure the economic system is one question, but even if we can’t, I feel like within that, there are lots of things we can do to make the technology work better.

Laine Perfas: Martin, one thing you mentioned earlier was an effort to democratize the technology. When I think about the technology being as widely available as it is, that requires a lot of trust in one another, and we don’t have a lot of that going around these days.

Wattenberg: That’s a very important point. And the idea of like, how do we democratize the technology without making it too easily usable by bad actors. It’s hard. I don’t know the answer to this. I do think this is where this idea of observation comes in. To go back to a metaphor Sheila used before was a car, of brakes and accelerator. And when I think about driving a car, what makes a safe driver? Is it access to brakes and accelerator? Yeah, that’s part of it, but what you really need is clear vision. You need a dashboard, you need a speedometer, you need a check-engine light, you need an airbag. And in a sense, thinking in terms of just brakes or acceleration is a very narrow way to approach the problem. And instead we should think about, OK, what is the equivalent of an airbag? Are there economic cushions that we could create? What is the equivalent of a speedometer, of a fuel gauge? This is why I believe that, and literally this is what my research is largely about at this point, is understanding both what neural networks are doing internally and thinking about their effects on the world. Because I think if you’re going to drive, it’s not just a matter of thinking do I speed up or slow down, but you really have to look around you and look at what’s actually happening in the world.

Jasanoff: If I could double down a bit, the brake and the accelerator, of course, are metaphors. And I was making the point that as a society, we tend to favor certain kinds of developments more than others. The stop, look, be wise, be systemic, do recursive analysis, those are things that we systematically do not invest the same kind of resources in as “move quickly and break things.” One of the things we have to cultivate alongside hubris is humility, and I think you and I are on the same page, and Susan too, that it has to be a much more rounded way of looking at technological systems. Again, I’m an environmental lawyer and on the whole, we started investing in waste management much later than we started investing in production. And we needed some really big disasters, such as the entire nuclear waste problem around the sites where the nuclear weapons plants are built. And now people, of course, recognize that. With AI, there are going to be consequences, and some of them will be, as you said, good surprises, and others of them will be bad surprises. Let me use a different driving metaphor: Are we awake at the wheel, or are we asleep at the wheel? I think the question whether we can be globally sleepwalking is a genuine, real question. It’s not something that AIs have to invent for us.

Wattenberg: Yeah, when I hear you talking about the car, you’re also talking about looking ahead, looking out the window, trying to figure out what’s going on. And I think that’s the key thing. It’s figuring out what are the things we want to worry about. There are things that you’ve alluded to that were genuine disasters that took decades for people to figure out. And one of the things I think about is if we could go back in time, what structures would we put into place to make sure we were worrying about the right things? That we press the brakes when necessary. We accelerate when necessary. We turn the wheels when necessary. What sort of observational capabilities can we build in to gain information to see where we’re going?

Laine Perfas: What is the role of universities and research institutions in this conversation as opposed to someone who might be using the technology for profit?

Wattenberg: I feel like there’s actually tremendously good work happening both in industry and academia. I also do think that these systems are somewhat less opposed than we believe. But I do think there is a big difference, which is that in a university, we can work on basic science. That can happen in industry too, but it really is something that is the core mission of the university, to figure things out, to understand the truth. And I think that attitude of trying to understand, there’s a lot the university can offer.

Jasanoff: We in liberal arts universities have been committed to the idea that what we’re training is future citizens. And so we take advanced adolescents and produce young adults. And during those four years, they undergo a profound transformation. I think that if we put side by side with the acquisition of knowledge, the production of citizens, then I think that there’s actually a huge promissory space that we are not currently filling as we might. What do we need to do to take citizens of the United States in the 21st century and make sure that, whether they go into industry or whether they go into the military or whatever, certain habits of mind will stay with them? A spirit of skepticism, a spirit of modesty, I think that is every bit as important a mission as knowledge acquisition for its own sake.

Laine Perfas: I want to pivot a little bit; we’ve been talking a lot about the threats and the concerns. A lot of you have also done work with very exciting things in AI.

Murphy: One thing that I’m excited about in terms of AI is you’re seeing hospitals use AI to better allocate scarce resources. For example, identify people who are most likely to have to come back into the hospital later, and so then they can allocate more resources to these people to prevent them from having to re-enter the hospital. Many resources, particularly in the healthcare system, are incredibly scarce. And whenever AI can be harnessed to allocate those resources in a way which is more equitable, I think this is great.

Wattenberg: I have to say, there’s a massive disconnect between the very-high-level conversations that we’re having and what I’m seeing anecdotally, which is this sort of lighthearted, mildly positive feeling that this is fun and working out. And I know of several people who are junior coders, for example, who will just talk to ChatGPT to help understand code that maybe colleagues have written. And they get great answers and they feel like this is this significant improvement to their life and they’re becoming much more effective. They’re learning from it. That’s something that I would just point to as something for us in the academic world to look at carefully.

Jasanoff: Any sort of powerful technology, there are these dimensions of whether people can take the technology and make it their own and do things that set creative instincts free. I’ve certainly found among my students who are adept at using AIs that there’s a lot of excitement about what one might call sort of creativity-expanding dimensions of the technology. But then there are creativity-dulling aspects of the technologies as well.

Laine Perfas: What are things that would be helpful to consider as we think about AI and the place it will have in our future?

Wattenberg: I have one, I would say, prime directive for people who want to know more about AI, which is to try it out yourself. Because one of the things I’ve discovered is that learning about it by hearsay is really hard. And it’s very distorting. And you often hear what you want to hear, or if you’re a pessimistic person, what you don’t want to hear. Today, you have any number of free online chatbots that you can use. And my strongest piece of advice is just try them out yourself. Play with them, spend a few hours, try different ways of interacting, try playful things, try yelling at it, try giving it math problems if you want, but try a variety of things. Because this is a case where, like, your own personal unmediated experience is going to be an incredibly important guide. And then that’s going to very much help you in understanding all of the other debates you hear.

Jasanoff: I’m totally in favor of developing an experimental, playful relationship with the AIs, but at the same time keep certain questions in the back of one’s mind. Who designed this? Who owns it? Are there intellectual property rights in it? When I’m playing with it, is somebody recording the data of me playing with it? What’s happening to those data? And what could go wrong? And then the single thing that I would suggest is, along with asking about the promises, ask about the distributive implications. To whom will the promises bring benefits? From whom might they actually take some resources away?

Laine Perfas: Thank you all so much for such a great conversation.

Murphy: Thank you.

Laine Perfas: Thanks for listening. For a transcript of this episode and to see all of our other episodes, visit harvard.edu/thinking. This episode was hosted and produced by me, Samantha Laine Perfas. It was edited by Ryan Mulcahy, Paul Makishima, and Simona Covel, with additional support from Al Powell. Original music and sound design by Noel Flatt. Produced by Harvard University.

Recommended reading

- Will ChatGPT supplant us as writers, thinkers? by The Harvard Gazette

- How artificial intelligence learned language by The Harvard Gazette

- AI is coming fast and it’s going to be rough ride by The Harvard Gazette

- The Ethics of Invention by Sheila Jasanoff

- Martin Wattenberg: ML Visualization and Interpretability on The Gradient podcast