View of the sign that marks storied Irving Street in Cambridge. William James, e.e. cummings, Julia Child, Marion and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Martin Karplus, and Gerald Holton are among the many notable residents that have called Irving Street home. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Storied Irving Street paves way to history

The Victorian lane has been an inspirational home to a famed psychologist, poet, chef, historian, chemist, and physicist

Old streets can be resonant with the past even into the present. And when astonishing people live (or have lived) on them in great numbers, such roads deserve biographies of their own.

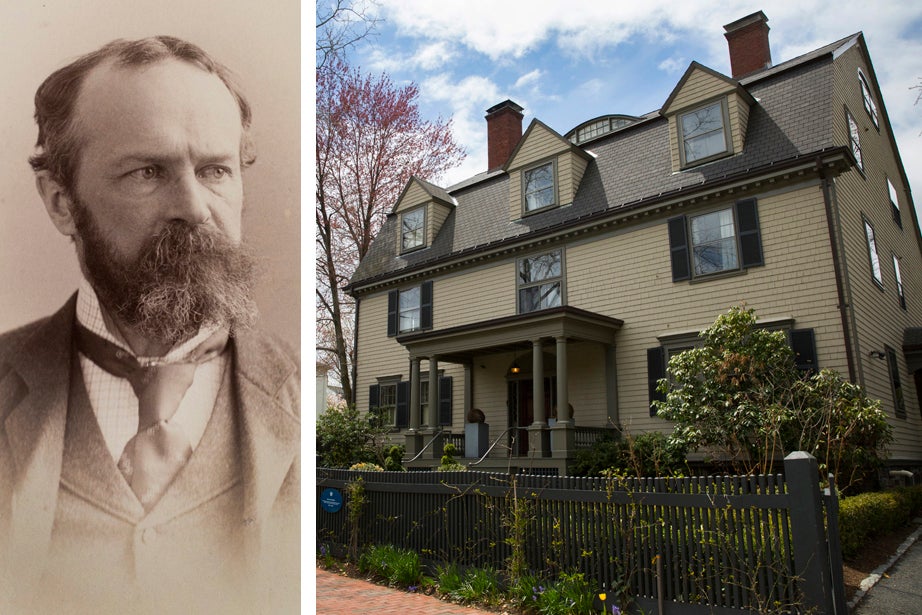

In Cambridge, for instance, consider the stretch of Irving Street north of Kirkland, where in 1889 psychologist and philosopher William James built the first house in a four-lane, 24-acre subdivision called Shady Hill. The section of Irving Street, a meandering 200 yards long, had just a year before been the driveway of the famed Norton Estate. So the biography begins.

PSYCHOLOGIST

One August morning in 1889, still clad in his nightshirt, James (1842-1910) stood at the window of a friend’s house and gazed at his house being built. It looked almost ready, he wrote to his brother Henry, the novelist. But carpenters were still at work on what William later called his “Elysium.”

James’ earthly heaven was three stories, big and square, with three chimneys, a gambrel roof, and brown cedar shingles. He helped design it, and meddled so much that the contractor told James he could save several thousand dollars simply by moving to Europe for the summer. On the first floor was a commodious library with floor-to-ceiling bookcases. Light streamed in through a triple-wide window. Upstairs was a small study where James did his writing at a stand-up desk, in complete quiet.

Quiet was the charm of 95 Irving St. As a newlywed in 1878 and as a new father soon after, James and his wife, Alice Gibbens James, had rented furnished rooms at the corner of Harvard and Ware streets in Cambridge, narrow quarters where the baby’s wails soon had the young professor on edge. In 1880, returning from Europe, James found himself the head of a household without a house. Cash-strapped, he and his young family moved into rooms in Boston’s Louisburg Square, where James was horrified by noisy neighbors and cooking odors.

By the fall of 1889 the prospect of the expansive Irving Street house was so attractive that James moved the family in even before the interior was finished. He lived there in academic, social, and familial bliss until his death in 1910. His wife lived there a decade longer, and his children and grandchildren until 1968.

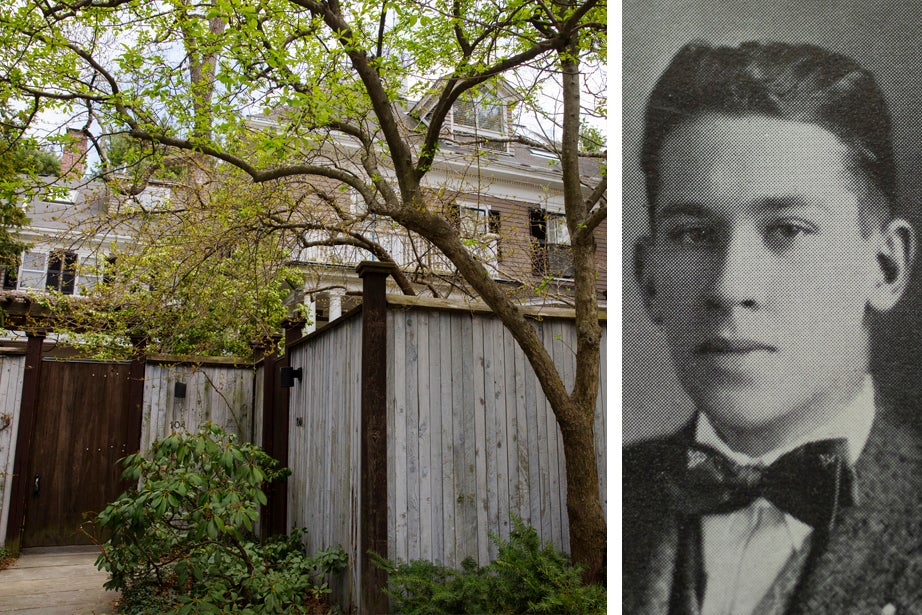

POET

Edward Estlin (E.E.) Cummings (1894-1962) was born and grew up at 104 Irving St., just across from James, a man he grew to think of as his informal godfather. The future World War I memoirist and bad-boy poet, just 15 when James died, owed the older man his life. In 1888, James introduced his friend and fellow Harvard professor, the Rev. Edward Cummings, to his research assistant, Rebecca Haswell Clarke, whose family dated back to the Mayflower. She became Cummings’ wife. Cummings later told his son that the three-story Walker & Kimball clapboard house at 104 Irving, a near-mansion with 13 fireplaces, was built “to have you in.”

In the midst of a neighborhood of groomed yards and groomed occupants like James and Harvard philosopher Josiah Royce, the Cummings’ house represented a touch of the nature-love and joyful anarchy that the poet later displayed on the page. The triangular yard was a riot of playthings — sandbox, swings, tree house — to which the neighborhood children had free entry. The everyday hubbub included a handyman named Sandy, a dog named Hamlet, a house full of books, and nearby Norton’s Woods.

At the turn of the 20th century, the woods — the very edge of the wilderness in 17th-century Cambridge — were still regarded as remote, expansive enough to contain gloom and mystery. Cummings mentioned them in 1952, during one of his “i: six nonlectures,” delivered at Harvard that year and in 1955 as the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures. Nature also loomed large in his memory of the Irving Street house itself. It had an oval front lawn, Cummings recalled for his audience, a white pine hedge, and two apple trees that every spring “lifted their worlds of fragrance toward the room where I breathed and dreamed.”

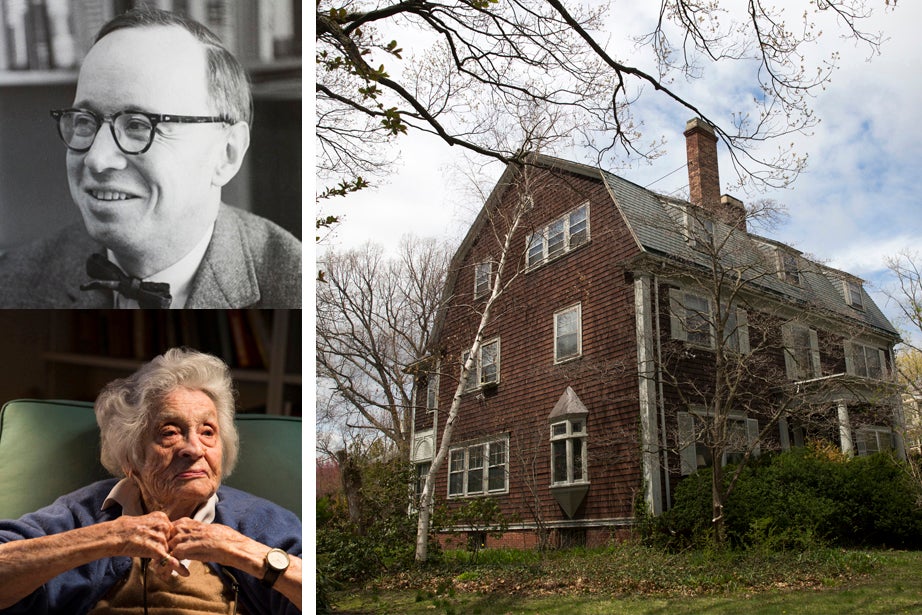

HISTORIAN AND ARTIST

Born in 1912, writer and artist Marian Cannon Schlesinger grew up on Divinity Avenue in Cambridge, the daughter of a Harvard professor. As a girl she regarded nearby Irving Street as so remote it seemed “a million miles away.”

She had a far-flung, adventurous early life. In 1929, Schlesinger accompanied her novelist mother, Cornelia James Cannon, three sisters, and an aunt on a three-month car trip in Europe, where she still remembers being served salted almonds by Alice B. Toklas. (Her mother and Toklas’ partner, author Gertrude Stein, both had studied with William James at Radcliffe College.) After graduating from Radcliffe herself in 1934, Marion traveled for a year in China to study painting, an experience reflected in her magical artwork. “I’m known for my horses,” she allows.

She and her husband, noted Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. (1917-2007), moved to Irving Street in 1947. They were only the second owners of the chocolate-brown frame house occupied in 1893 by Harvard zoologist E.L. Mark. Its price then has some shock value now: $17,000. “We don’t belong,” said Schlesinger, who will be 104 in September, with a laugh. “Everyone else is a millionaire.”

Nothing much has changed. “I tell people we kept it historically accurate,” said her son, writer Andrew Schlesinger ’70, who lives with her. Schlesinger pointed to the couch where President-elect John F. Kennedy sat in January 1961 to meet with future advisers, including Arthur. She remembers JFK charging up the stairs to take a phone call in her sewing room.

Starting in the 1950s, she and her husband started a tradition of big Commencement day parties, later continued into the 1990s by economist John Kenneth Galbraith. “We used to have parties all the time,” said Schlesinger of her first decades on Irving Street. “Nobody has parties anymore.”

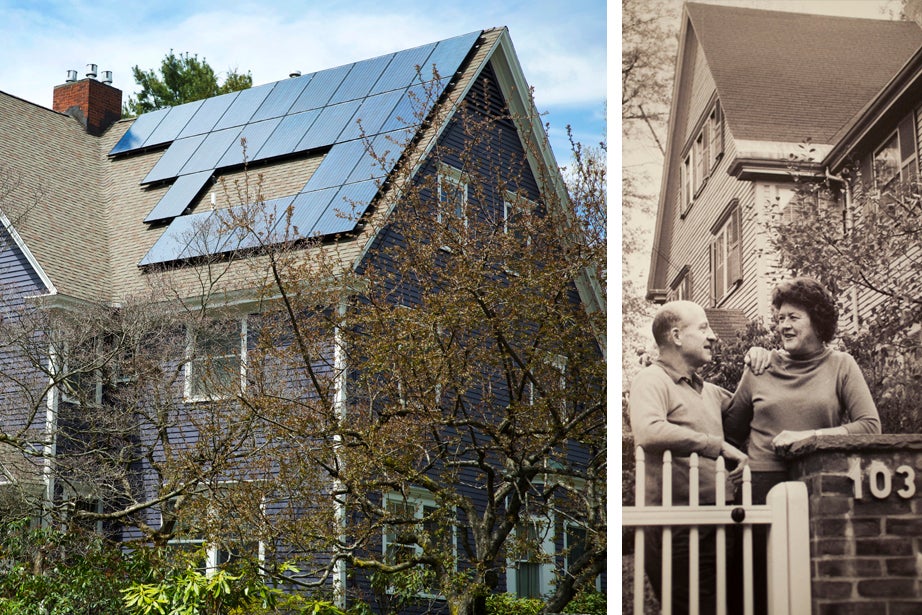

CHEF

Julia Child (1912-2004) was a California-born champion of French cookery, the first celebrated television chef, and a woman who, incidentally, could never see the point of dining rooms. She and her husband, diplomat Paul Child, moved into 103 Irving St., the former Royce household, in the summer of 1961. They had first seen the house in 1958, just before a diplomatic posting (their last) to Oslo, Norway. “It spoke to us the moment we walked in the door,” she wrote.

Since the end of World War II, the couple had lived mostly in Europe, and at the end of their peripatetic phase decided to put down roots on Irving. The large gray clapboard house had a spacious kitchen with two pantries, two living rooms, a big basement, and a large room on the second floor that would suit Paul as a study. “The kitchen proper was our major concern,” Child wrote, since it was, not surprisingly for her, “the beating heart and social center of the household.”

It was the 17th and last kitchen the couple designed. “We intended to make it both practical and beautiful,” she wrote, “a working laboratory as well as a living and dining room.” It included a gas stove scaled for a restaurant and a set of wall ovens. The countertops, designed by Paul, were 38 inches high, 2 inches above standard to accommodate Julia’s height (6 feet, 2 inches).

The house had a little yard and a small driveway. It had wisteria that Paul, a gardener, tried for years to coax into bloom. (They finally flowered the year he died at age 92.) “Surrounded by friends and large shade trees,” Child wrote in remembrance, “we couldn’t ask for a happier place to live.”

NOBEL LAUREATE

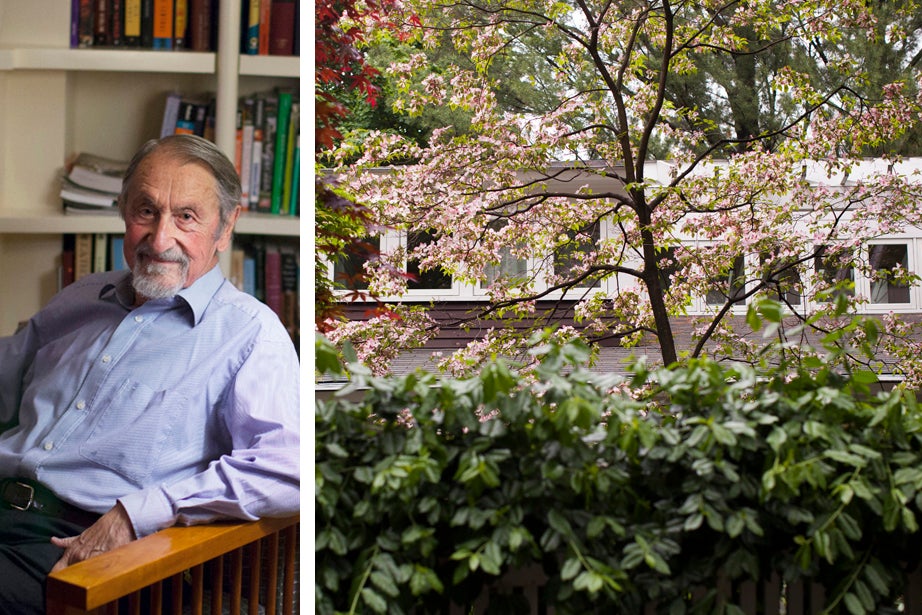

A beloved dwelling, wrote French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, is “Egg, nest, house, country, universe.” That feeling of peace and completeness is evident in the house on Irving Street that 86-year-old Martin Karplus, winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in chemistry, shares with his wife, Marci. There is a 6-foot fence out front, lush with clinging ivy that encloses the house. The fence is so high, said Martin, that in the past only their tallest neighbors ever appeared above it as they walked by: Child and Galbraith.

“It’s a very interesting neighborhood,” said Martin, acknowledging his accomplished neighbors, present and past. He and Marci bought the ranch-style house in 1983, after hearing about it before a “for sale” sign went up.

Peace did not come right away. “The first thing we did was demolish the inner part of the house,” Marci said, “which gave the living room a vaulted ceiling.” Years later, when they made the first addition to the house, workmen hit a bed of manure. They had struck the foundations of an old Norton estate barn. More recently, in 2008, the Karpluses added a second story and put in a long set of skylight windows upstairs, essentially making it their “tree house.”

Martin does much of his work in the dining room, next to French doors that frame a compact backyard lined with old trees. It looks like a miniature forest from a fairy tale. In daytime, light floods the interior.

“I like to work surrounded by light and greenery,” said Martin. As a boy, he and his family escaped Nazi rule. They lost their house in Vienna.

PHYSICIST

Gerald Holton was another young refugee from Nazi-era Vienna when luck (he says) landed him in an American college. A question plagued him there nearly to the end of his bachelor’s degree: major in literature or physics? He chose the world of Newton over Shakespeare, but he never abandoned writing, and to this day can be described as a polymath, one of many who feel right at home on intellectually diverse Irving Street. (Karplus is a photographer and chef too.)

Over seven decades Holton’s scholarship has ranged from the physics of liquids under high pressure to editing the collected letters of Albert Einstein to writing about the sociological fate of wartime European refugees, the state of American schools, and the plight of women in science. His wife Nina, who also was a teenage refugee from Vienna, is a sculptor. (In New York’s Greenwich Village, she once lived across from Irving Street’s E.E. Cummings.)

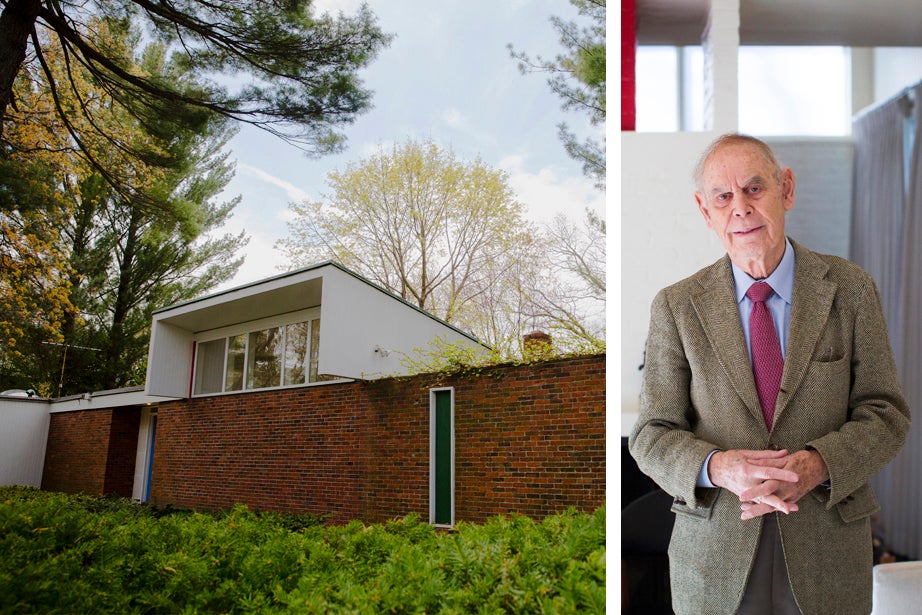

The Holtons bought a house on the end of Irving Street that is an architectural treasure: the self-designed home of Spanish architect Josep Lluís Sert (1902-1983). It is the only modernist, or even modern, house on the street. The Holtons were guests there many times after Sert took up residence in 1958. Now they call the iconic house their own, with its light-filled rectangle of rooms and its three courtyards, all based on architecture’s “golden ratio” of proportionality.

“I knew this house and knew the aesthetic value of it,” said Gerald, describing its serenity, privacy, and touch of European culture, “where we came from.” But when they bought the house in 1991, “it was in need of enormous repair,” he said. Renovations took six months, but restored the serenity of the original. Living there since, said Nina, “has been heaven.” That feeling is enhanced by every view’s greenery. “It makes you feel inside,” said Gerald, “as if you were outside.”

Outside, where dead-end Francis Avenue is “rescued” by Irving Street, said Gerald, the tree-lined neighborhood itself retains a touch of the old Norton’s Woods. Within that area, an exclusive enclave has grown. Gerald searched for a way to define Irving and its environs. He said, “This is a village.”