Director and editor Ned Brown; cinematography by Joe Sherman, Kai-Jae Wang, and Ned Brown/Harvard Staff

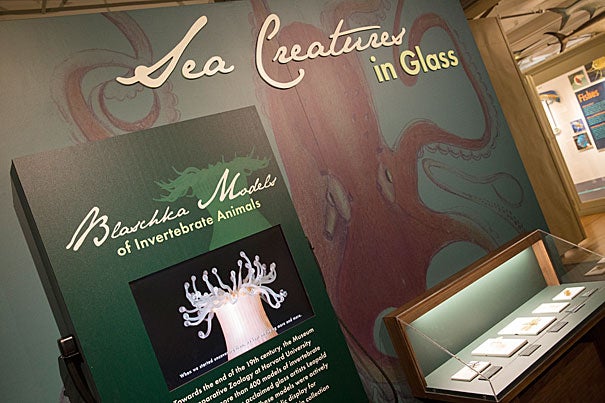

Putting the Glass Flowers in new light

Gallery set to reopen after major renovation

More like this

What do they mean by glass flowers?

That’s what Donald Pfister wondered when he embarked on his first trip to see the jewel of Harvard’s botanical collection as a graduate student.

“I was at Cornell and everybody said, ‘You have to see the Glass Flowers,’” said Pfister, who today is Harvard’s Asa Gray Professor of Systematic Botany and curator of the Farlow Library and Herbarium of Cryptogamic Botany. “Of course, my reaction [on seeing them] was what everybody’s reaction is: ‘They can’t be glass. How did they do that?’”

On May 21, after the most extensive gallery renovation in the collection’s history, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka’s celebrated creations will again be available to those intrigued, as Pfister was, by the notion of flowers made of glass.

The Harvard Museum of Natural History gallery that houses what is officially the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants has undergone a top-to-bottom facelift. Among the upgrades: renovated wooden display cases, new panels with explanatory material, and space set aside for temporary displays that highlight portions of the collection beyond those on permanent display. Other changes include refinished floors, a new ventilation system, and new lighting.

Collection manager Jennifer Brown said the result is an improved and updated gallery that hasn’t lost any of the charm, character, or feeling of the original exhibit. Though fewer of the collection’s 4,300 models will be on display at once, the new opportunity to mount temporary displays will allow visitors to see more of them over time.

“We will have the chance to pull things out of storage, tell different stories, and develop new content,” Brown said.

The first temporary exhibition will include specimens from the collection’s pollination series, which shows lifelike examples of bees and other pollinators in action. Next up will be the popular “rotting fruit” series, a collection of rosaceous plants and plant diseases.

The flowers themselves also got some attention. They were removed from their cases, carefully cleaned and, in some cases, repaired and remounted.

“The space is just completely transformed,” Brown said. “I can’t wait to have all of these parts in a fantastic final product. The space is better for our visitors and for the collection itself.”

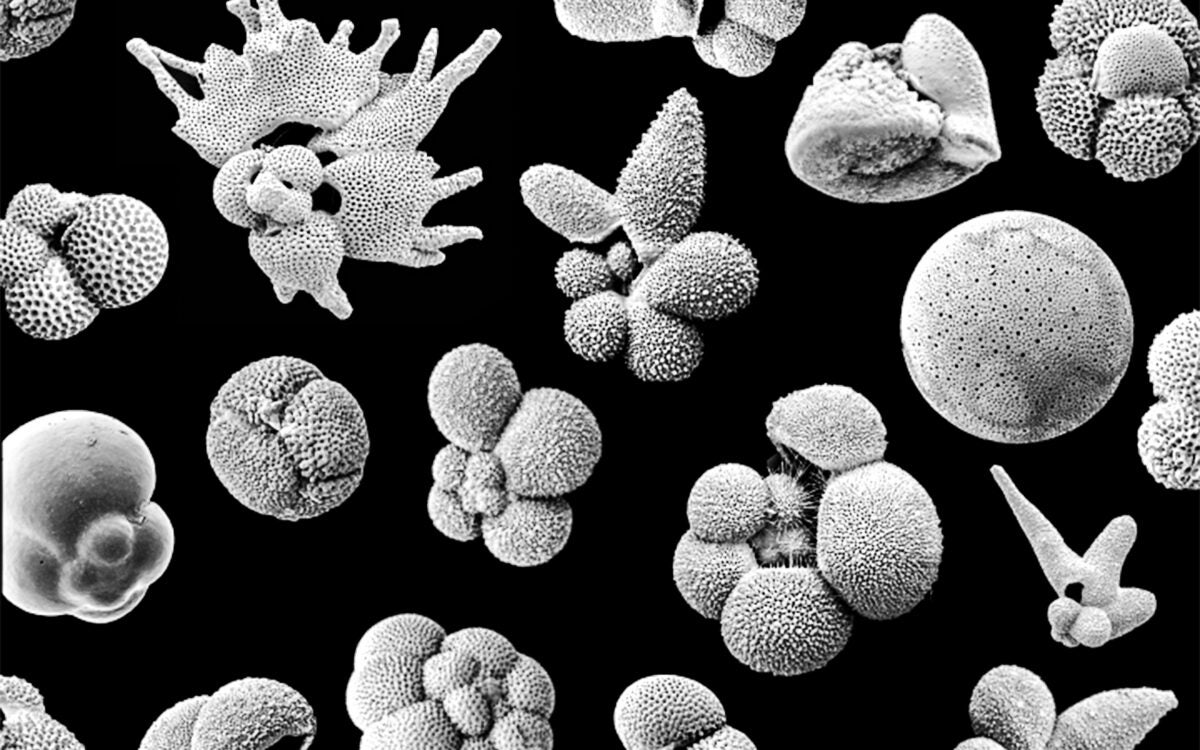

The collection was assembled between 1886 and 1936, when the study of plants was largely limited to examining dried specimens — flattened, with colors muted — or observing living specimens in the field.

It got its start when George Goodale, the Botanical Museum’s first director, saw glass sea creatures that the Blaschkas were making and selling via mail order and thought that similar representations could aid in teaching botany.

“I think what Goodale saw was [the] educational piece: How do you present plants, that are ephemeral in the world?” Pfister said.

Goodale contacted the Blaschkas, a father and son team of German glass artists, and asked them to create plant models. They agreed. The glass plants were contracted solely to Harvard — with the financial support of the Ware family — making the collection unique.

But the collection’s fame rests not on its uniqueness or even its breadth — it includes ferns, fungi, bryophytes, and algae as well as flowering plants — but on its accuracy and beauty, Pfister said.

“We think of glass as shiny and smooth,” Pfister said. “If one looks at the models … they’re wonderfully realistic, the colors are vivid and accurate. The model of the maple, for example, is just a fantastic model to see because it’s like being out in the forest in the fall.

“You have this wonderful combination of artistry and accuracy. One can count stamens, one can look at the flower parts and say, ‘Of course, that’s exactly right,’ and yet they’re beautiful.”

The exhibit includes the Blaschkas’ workbench, which holds evidence the pair used ordinary tools — not the “secret” method of long-lasting rumor.

“As long as the Glass Flowers have been around there have been rumors of how they were made,” Brown said. “The collection was a result of their skills, their observational talents, and their dedication to the project.”

The updated exhibition is supported by a gift in memory of Melvin R. Seiden ’52, LL.B. ’55, and a grant provided by the Massachusetts Cultural Facilities Fund, a state program administered through a collaborative arrangement between MassDevelopment and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. The conservation of the Glass Flowers is supported by a gift from George Putnam III ’73, J.D. ’77, M.B.A. ’77, and Kathy Putnam.