Harvard’s Colonial North American Project website includes 150,000 images of diaries, journals, notebooks, and other rare documents from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A digital portrait of Colonial life

Wealth of detail in wide-ranging archival project

“Dear Sister,” wrote John Hancock on May 1, 1754, as a 17-year-old Harvard student, “I wish you would spend one hour in writing to me.”

Before leaving what years later would become his famous signature, he wrote, “Your ever loving brother, till death shall separate us.”

The letter to his sister Mary, shedding light on Hancock’s raw emotions as he studied in Cambridge in the years before the Revolution, is a sample of the riches in manuscripts and archival material available online at The Colonial North American Project at Harvard University.

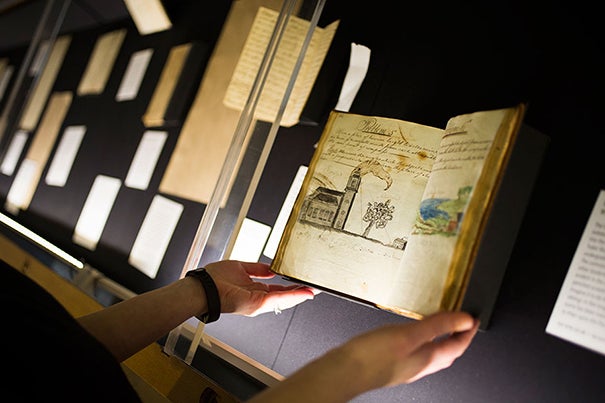

Launched Monday, the website of the Colonial North American Project so far includes 150,000 images of diaries, journals, notebooks, and other rare documents from the 17th and 18th centuries.

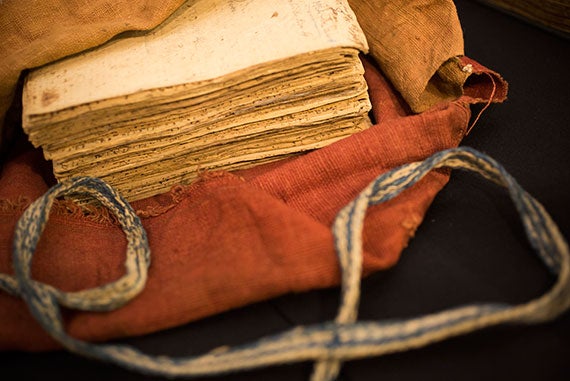

Part of the University’s endeavor to digitize all its collections and make them available free of charge, the Colonial North American Project is unique because of its scale. According to a 2011 survey, the material is scattered through 12 repositories — from Houghton Library to the Harvard University Archives to Loeb Music Library.

In elegant script, the documents provide a glimpse into the life of North American colonies through the eyes of real people who wrote about family affairs and daily life but also about slavery, Native Americans, education, science, and revolution.

“We’re bringing history alive,” said Franziska Frey, the Malloy-Rabinowitz Preservation Librarian and head of Preservation and Digital Imaging Services.

“It’s a treasure of cultural heritage,” added Frey, who is overseeing the digitization process and the overall project. “If photography would have existed at the time, we would have found photographs in our collections.”

In many of the diaries and journals, fanciful yet vivid illustrations accompany meticulous details of life and death, painting a dramatic picture of the Colonial era.

For example, Harvard mathematics Professor John Winthrop kept account of all the deaths, in a “bill of mortality,” in Cambridge between 1759 and 1768. He wrote there were “235 deaths in 10 years.” Among the most common causes, he noted, were accidents, fever, consumption, and dysentery.

Winthrop, who taught at Harvard from 1738 to 1779, was matched in avid note-taking by his wife, Hannah. Both kept diaries, journals, and personal almanacs. Their son James, a justice of the peace, followed the family tradition. In one journal entry, he wrote: “On the fourth day of December in the year of our Lord 1791, I joined in marriage Cato Bancroft & Nancy Cutter, both of Cambridge, negroes.”

The Winthrop family documents are among those showcased in the “Opening New Worlds” exhibit in Pusey Library, to run through March. The exhibit includes a notebook with lecture summaries for a physics course given by Winthrop. It also features handwritten sermons by the Rev. Samuel Willard, who led Harvard in the early 18th century, as well as the teenage Hancock’s letter.

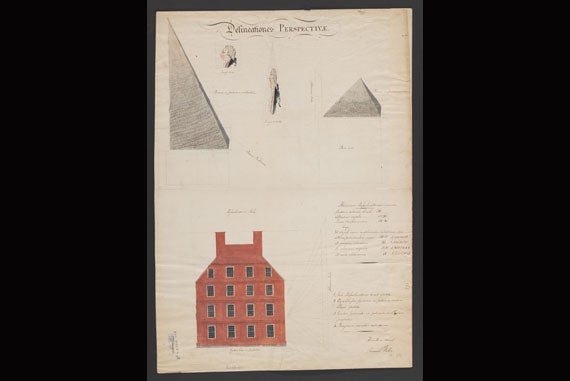

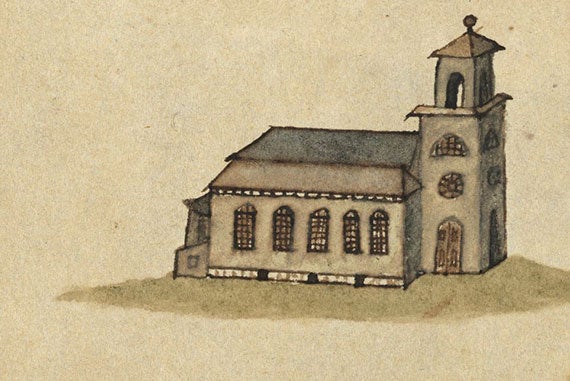

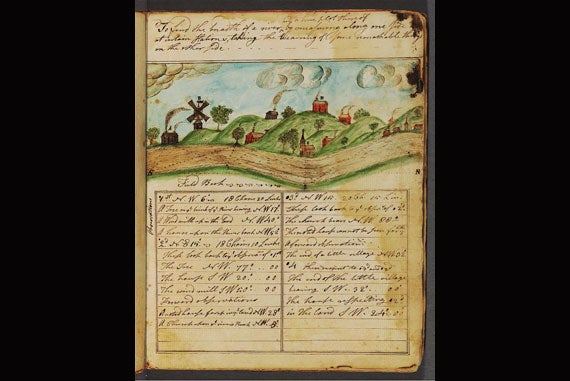

Student notebooks from the era, many distinguished by their illustrations, are also part of the exhibit. In his math notebook from 1782, Joshua Green included a watercolor rendering of a quaint village crossed by a river to explain how to survey a river.

A glimpse inside

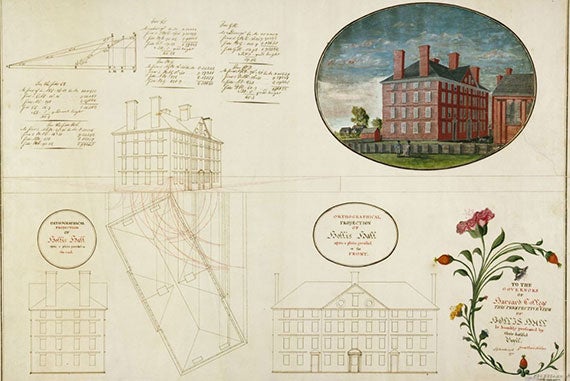

A pen-and-ink drawing of an “end view of Massachusetts Hall” by Samuel Welles. Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

A watercolor of Christ Church (ca. 1781) by Joshua Green is among the 150,000 items in Harvard’s collection. Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

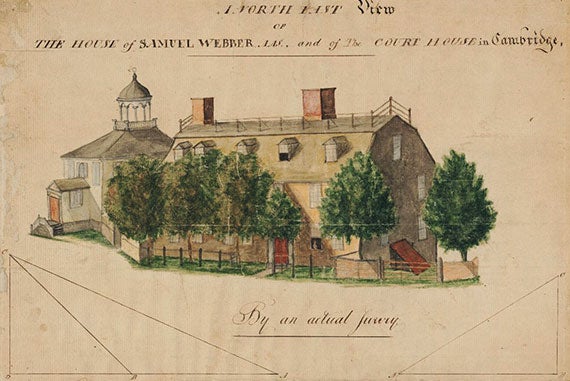

William Boyd’s watercolor, “A North East view of the house of Samuel Webber, A.A.S., and of the Court House in Cambridge, by an actual Survey,” is remarkable in its detail. Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

A page from Samuel Griffin’s “Mathematical manuscript.” Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

An inscription on this illustration reads: “To the Governors of Harvard College this Perspective View of Hollis Hall is humbly presented by their dutiful pupil Jonathan Fisher, September 27th, 1791.” Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

On a recent morning, Saira Haqqi and Abigail Merritt, interns with the Weissman Preservation Center, handled some of those notebooks and relished the experience.

“It’s part of the joy,” said Haqqi, “being close to these objects.”

Merritt agreed: “It’s amazing to see how the individuality comes out in the handwriting and the drawings.”

With 150,000 images, the Colonial North American Project, supported by the Arcadia Fund and the Sidney Verba Fund, is one-third complete, said Megan Sniffin-Marinoff, University archivist. Work is ongoing at several libraries to digitize the remaining 300,000 images of Colonial North American manuscripts in 1,654 collections.

“We discovered material that hadn’t been well cataloged, that may have been hidden or forgotten,” said Sniffin-Marinoff. “We want to bring it all out.”

A panel with presentations on the history and scope of the Colonial North American Project will be held at 3:30 p.m. Thursday at Lamont Library.