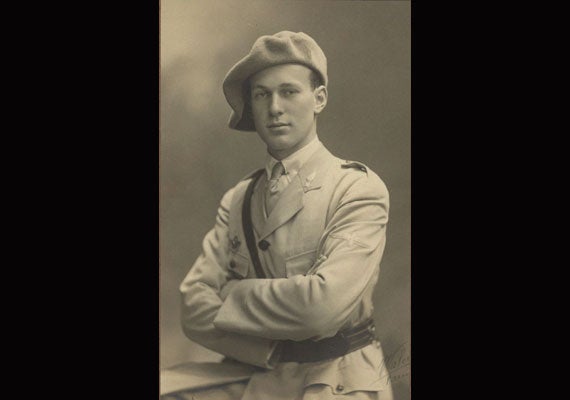

World War I was a theater of action, or getting ready for action. Alan Seeger ’10, a private in the Foreign Legion of the French Army, was killed in action on July 4, 1916 (photo 1). Members of the Harvard ROTC, circa 1918, dig practice trenches at Fresh Pond (photo 2). In this circa-1919 image, the Radcliffe Unit’s Anna Holman ’14 (right, photo 3) crank-starts the Red Cross vehicle she drove in France.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives; (photo 3) courtesy of Schlesinger Library/Radcliffe Institute

‘The choicest of their kind’

How Harvard responded to the Great War

This is the first in a series of occasional articles marking the centennial of World War I.

On Thursday, June 18, a century ago, Harvard College graduated its Class of 1914. “We close old records,” one senior wrote in the class album that year, and “open new.”

The world itself was closing old records and opening new ones — most of them vast and violent. Ten days after Harvard’s graduation, a dour European royal with a curlicue mustache and a helmet of green feathers was gunned down with his wife in Sarajevo. Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s death by a single pistol shot set the stage for the official start of World War I just a month later, on July 28, 1914.

The four-year conflict killed 16 million people, and stripped England, Germany, and France of a generation of young men. With its swarming armies and globe-spanning troop movements, World War I also accelerated the 1918-1920 flu pandemic. Worldwide, up to 100 million died — 3 percent of humanity.

Setting Harvard into the context of a catastrophic world war and its aftermath may seem, in retrospect, petty. But the events of 1914-1918 hit the University hard. A look back reveals how Harvard helped determine the course of the war and how it demonstrated the response to the war by America’s educated classes.

The University was at ground zero of a movement to prepare an American officer corps. It also illustrated the architecture of America’s involvement — an ever-bigger structure built of romance, anger, and what was widely perceived as a quest for world liberty and justice.

Then there was the fighting. Harvard men were quick to join the fray. Some were beholden to their native lands, including Germany. (At least four Harvard graduates died in combat for the Kaiser.) Others from the University rank and file and its diaspora of alumni were early volunteers: ambulance drivers, medical experts, aid logicians, and reconstruction experts.

Through Radcliffe, Harvard helped break the idea that war was only for men. Philip C. Lewis ’17, who quit the College to drive an ambulance at the front, was shocked at the dearth of young men in Europe’s cities, and sobered by who took their places. “In London, and in Paris,” he wrote, “women are seen doing men’s work in countless ways.” Anna Holman ’14 represented responses to the war by many American women. She was sent to France in 1918 by the War Work Committee of Radcliffe, worked as a driver, transported the sick, and delivered hospital supplies.

Harvard graduates also produced some of the war’s enduring literature. “The Enormous Room” (1922), an autobiographical novel by ambulance driver (and later poet) E.E. Cummings ’15, captured the mixed feelings veterans had toward the war’s end — along with the rich palette of adventure observers could draw from.

“I have seen many extraordinary and never-to-be-forgotten things — it seems very often that life cannot possibly hold more,” British artillery officer Charles D. Morgan ’06 wrote in 1916. Despite being wounded, he added, “I shall never regret going to this show.”

Finally, Harvard joined in national tropes of how the war was remembered and enshrined — starting with a Roll of Honor photo show of the dead in 1920 (Gen. John Pershing laid the first wreath) and culminating in the Memorial Church at Harvard, completed in 1932.

Quick to act

A few Harvard graduates and students were in combat within weeks of the war’s start, including men in French, English, Scottish, Canadian, and German units. The early entry of other Harvard men — Americans not yet required to serve — was accelerated by a tradition: Summer was a time for student and postgraduate travel in Europe, and the summer of 1914 drew the adventurous into war’s grip.

Many others not already in Europe sped across the sea, summoned to duty. George Williamson ’05, already a reserve British Army lieutenant, was called to active service on Aug. 5, 1914, a day after England declared war on Germany. On Aug. 7, he set sail for England from his Montreal law firm, and by Sept. 8 he was in France, part of the fighting. He succumbed to wounds suffered in combat on Nov. 12, 1914 — the first Harvard graduate to die in the war and (it is believed) the first graduate of any American college to do so.

Harvard’s first American volunteer to die was Edward Mandell Stone ’08, who was living in France when war broke out. Immediately, in August, he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. Wounded by shrapnel on Feb. 15, 1915, Stone lingered for 12 days before dying. A Legion surgeon wrote later, “He had a lot of grit, poor chap.”

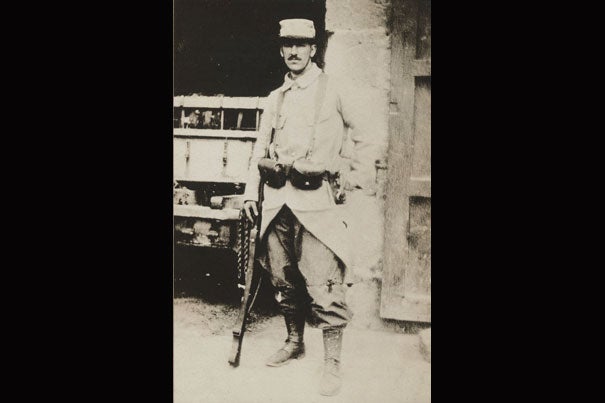

Enlisting in the Legion even earlier than Stone was Alan Seeger ’10, a budding poet whose work drew praise from classmate T.S. Eliot. For two years after graduation, Seeger lived a bohemian life in Greenwich Village before moving to Paris. He joined a month before the war started and was killed in action on July 4, 1916.

Williamson’s biography is the first entry in the five-volume “Memoirs of the Harvard Dead” (1920-1924), compiled and edited by Mark A. De Wolfe Howe. These volumes, illustrated with photographs of the fallen, are a testament to the scale of the University’s representation in the war. So is another book, the inches-thick “Harvard’s Military Record in the World War” (1921), which in 1,142 alphabetized pages of small type lists the name and service record of every Harvard participant.

Including alumni, undergraduates, and faculty, a total of 11,319 Harvard men served in the WWI military. About two-thirds received military commissions; 418 were decorated and 373 were killed. Of the dead, 43 had not yet graduated. A particular detail astonishes: Harvard men joining the military represented nearly 60 years of graduating classes, from 1864 (William Roscoe Livermore, born in 1843) to 1923 (Carl Richard Hauers, born in 1900).

Livermore, an engineer, attended the College for only a year, starting in 1860. He graduated from West Point in 1865, missing service in the Civil War by only two months.

Harvard and WWI

Theodore Roosevelt, Class of 1880, in his Rough Riders uniform. He helped lead the Preparedness Movement, a readiness campaign in which Harvard played a vital part. Courtesy of Houghton Library

Harvard men in training at Fort Oglethorpe, Ga., 1916. Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

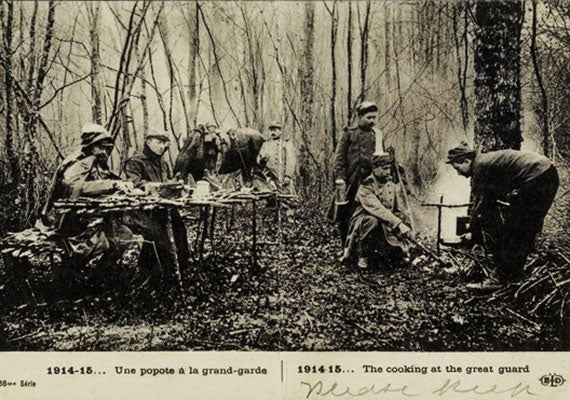

A 1914-1915 postcard sent home by Alan Seeger, Class of 1910, who served with the French Foreign Legion. Life for enlisted men was universally rough and elemental. Courtesy of Houghton Library

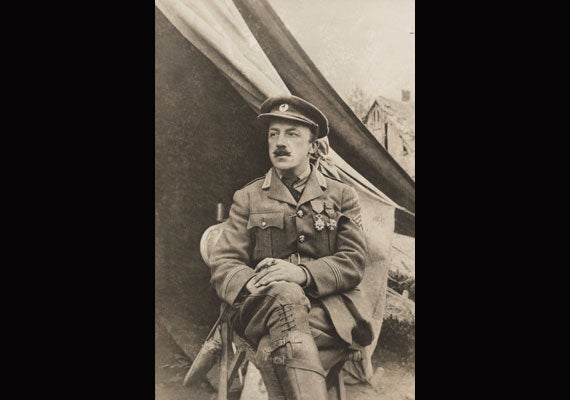

Richard Norton, Class of 1892, in an undated photo from the front. A peacetime archaeologist, he founded an ambulance service in 1914 and typified early war Harvard volunteers. Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

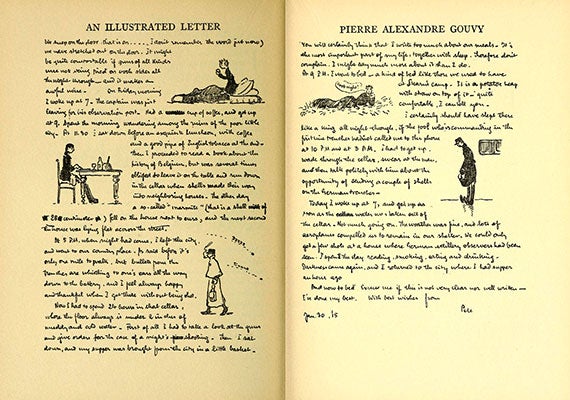

A January 1915 illustrated letter by French army artillery officer and Harvard business student Pierre Alexandre Gouvy, 1911/1912, reprinted in “The Harvard Volunteers in Europe” (1916). In an age of letter-writing, vivid correspondence poured home from the front lines. Open Library/Internet Archive

An undated photo of three members of the Radcliffe Unit, in France from 1917 to 1920 to help reconstruct villages. (From left) Lucy Stockton 1910 (who wrote an eye-witness account of combat), Julia Collier 1910, and documentarian Ann Holman 1914. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library/Radcliffe Institute

Four members of the Radcliffe Unit in France, circa 1919-1920. Mary Burrage 1914 (from left), Katherine Shortall 1912, Anna Holman 1914, Julia Collier 1910. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library/Radcliffe Institute

Red Cross medical volunteers, all Harvard men, in France, 1918. Capt. George Utasny 1898 (from left), Maj. Guy Lowell 1892, Lt. Col. Robert P. Perkins 1884, Capt. Robert W. Bates 1911. Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Ronald Wood Hoskier 1918/1919 (war degree), a fighter pilot with France’s Lafayette Escadrille. He was killed in action in 1917, shortly after his 21st birthday. He father wrote, “no more spotless life has been offered for humanity.” Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

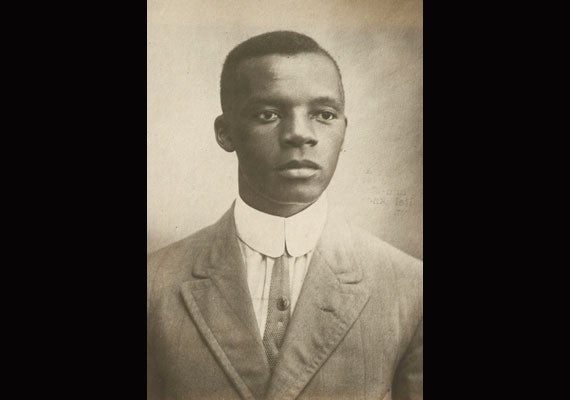

Alfred Frazier White, a student at Harvard Law School from 1916 to 1918, enlisted as an Army private in August 1918 and was dead from influenza by October — one of many pandemic-related deaths in the war. Courtesy of Harvard Film Archives

Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, who led the American Expeditionary Forces, visited Widener Library on May 30, 1920 — Memorial Day — to view the Roll of Honor, the collected photos of Harvard’s war dead. Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Doing their part

Noncombatant volunteers from the University poured into action well before the United States formally entered the war in 1917. From 1914 to 1917, 450 alumni and undergraduates went to the front as ambulance drivers. Looking around his ambulance unit in 1916, Lewis — who had received that earlier gender shock — observed that of 215 “college men” who were drivers, 90 were from Harvard. (Yale, he added, accounted for 25 and Princeton for 22.)

Starting in 1915, Harvard Medical School formed three successive medical units in France. They saw horrors, of course — men wounded by high explosives, shrapnel, bullets, and poison gas. In June 1915, Frank H. Cushman, D.M.D. ’15, busily treated soldiers’ head and jaw wounds. But he also took time to be horrified by the “appalling” condition of teeth among British enlisted men. The year before, he wrote, the invading German army had 500 dentists in uniform; soon after, their British counterparts brought along 15. (British rules held that dentures would not be fitted for any soldier who still had two teeth, as long as there was one in each jaw and they touched each other.)

American volunteer ambulance services were chiefly the inventions of Harvard graduates. Abram Piatt Andrew Jr., Ph.D. ’00, founded the American Ambulance Field Service. Before the war he had taught economics at Harvard and served as director of the U.S. Mint. Archaeologist Richard Norton ’92 founded the Norton-Harjes Corps, an ambulance service that by 1917 was absorbed into the American Red Cross.

Norton was another example of a sometimes forgotten aspect of WWI: Men and women of every class served. He was the son of Harvard art historian Charles Eliot Norton, and the youngest in a family that had sent sons to Harvard since the 17th century. In the spring of 1914, Norton was on a friend’s yacht near Corfu in the Ionian Sea. At anchor nearby was Kaiser Wilhelm’s yacht. The Harvard graduate frequently dined with the German emperor, who gave Norton a jeweled scarf pin. The war began just a few months later.

Norton died of spinal meningitis in August 1918. Writing about him later, De Wolfe Howe called his volunteer ambulance project “a practical medium for the expression of sympathy.”

The war produced other institutional inventions by Harvard volunteers. Norman Prince ’08, LL.B. ’11, a Boston banker’s son who trained with the Wright brothers, co-founded the Lafayette Escadrille. During the war he shot down five German planes and tangled in 122 aerial combats. He died in October 1916 from injuries suffered in a crash landing.

Another little-known institutional invention was staffed by Harvard men: the American Distributing Service, a relief organization started in August 1914 by Robert Woods Bliss ’00. It created a channel through which donated American goods streamed into the war zone — surgical supplies, shirts, socks, coffee, sugar, and other necessities, chiefly for hospitals. “Best of all,” wrote volunteer Langdon Warner ’03, “there is no red tape.” (An art historian and archaeologist, Warner later served as one of the “Monuments Men” during World War II.)

The Distributing Service was made up of noncombatants, as most early Harvard volunteers were. But it suffered at least one fatality: Charles Robert Cross Jr. ’03, who died in a 1915 road accident.

Other “volunteers” in the war had no sense of themselves as such. On May 7, 1915, five Harvard alumni were among 1,198 passengers and crew lost when a German U-boat sank the Cunard liner Lusitania. One of them was writer and artist Elbert Hubbard, Class of 1897. The event was a major one on the road to America’s official entry into the conflict, in April 1917.

American preparedness

One of the forms war fever took was a growing obsession with getting ready. In August 1915, the first of the so-called Plattsburgh camps was organized by Medal of Honor winner Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, M.D. ’84, LL.D. ’99, to give professional men four weeks of intensive military training. Of the 1,200 men who first registered, a third were from Harvard.

The camps were part of the preparedness movement championed by Wood and by former president Theodore Roosevelt ’80. Their aim was to prepare a corps of officers for the Great War.

In September 1915, Harvard offered its first elective course in military science. Students got academic credit; 560 enrolled, with Wood as a guest instructor. In December, Roosevelt wrote in the Harvard Advocate that Harvard should take the lead in preparing the nation for war.

In January 1916, the University mobilized its “Harvard Regiment,” and 1,000 students signed on. It became the first unit of the Army’s new Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), established six months later by the National Defense Act.

On Jan. 10, 1917, Harvard ROTC was celebrated in a special supplement to the Crimson. During the 1917-1918 academic year, there were 12 ROTC companies at Harvard, with 1,193 enrolled — more than any other college. By then, according to historian Frederick S. Mead, “Harvard to all intents and purposes became a Government military school.”

When the United States entered the war, enlistments and draft call-ups halved the University’s enrollment of 4,700 during the spring and summer. Only Harvard Medical School retained its normal size. By the fall of 1917, enrollment at Harvard Law School had dropped from about 850 students to 250. By the fall of the next year, enrollment at Harvard Business School had fallen from a pre-war level of 232 to just 32 students.

Three wartime naval schools were conducted at Harvard — one for members of the naval reserve, one for ensigns, and one for the United States Naval Radio School. (The radio school took place in Austin Hall, which was rented by HLS to the military. The resulting income eased the sting of slipping enrollments and lost tuition due to the war.

Meanwhile, Harvard scientists conducted secret research into poison gas, gas masks, sound-detection systems for anti-submarine warfare, and a system for pre-straining gun barrels. Among the researchers was a future Harvard president, chemist James Bryant Conant ’13/’14, Ph.D. ’16. He became an Army major in charge of a secret Ohio plant that made lewisite gas. (Conant was at Harvard’s helm during World War II, transforming the University into that conflict’s most-funded American research arm.)

The war effort required money too, and fast. In stepped another Harvard volunteer. During 1917-1918, John Price Jones ’02 was a key administrator of the war’s four Liberty Loan bond issues. In just 18 months, he helped raise $21 billon, two-thirds the cost of the war.

Heavy losses

By June 1917, about 40,000 American troops were in France. Only 11 months later, in May 1918, there were about 1 million — half of them at the front lines.

Harvard paid the price early. In September 1917, Lt. George Plummer Howe ’00, M.D. ’04, was the first American officer to be killed in the war.

The first high-ranking American officer to die in combat was also a Harvard man. Col. Reynal C. Bolling ’00, LL.B. ’02, a corporate lawyer, was a veteran of Plattsburgh camp training, and a pioneer in National Guard aviation. In March 1918, armed only with a revolver while trying to protect his unarmed driver, he died exchanging fire with two German infantrymen.

In the 18 months of the American phase of the war, Harvard’s toll mounted in concert with the nation’s list of the dead and wounded. There is a story in every face and inscription and in every letter home.

Fame offered no protection. In July 1918, 20-year-old fighter pilot Lt. Quentin Roosevelt ’19 died during aerial combat with three German aircraft near the Marne River in France. His Nieuport biplane crashed behind enemy lines. The Germans buried him with full military honors. He was the youngest of Theodore Roosevelt’s four sons, after Theodore Jr., Kermit, and Archibald.

All four went to Harvard and all four served in France. But it was Quentin who best articulated the building U.S. appetite for a war perceived as a fight for justice. In early 1917, he wrote to his fiancée of how contemptible it was for America to stand by “while England and France fight our battles and pan gold into our pockets.”

Military honors accrued. In the fall of 1918, during the massive Meuse-Argonne Offensive, two Harvard men were in command of the 77th Division’s “Lost Battalion.” Maj. Charles Whittlesey LL.B. ’08 refused to surrender. Capt. George G. McMurtry ’99, who had served with Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders at San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War, was wounded twice. Each received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Thousands died in the 47 days of that offensive, including 36 Harvard men. One was Lt. Francis Reed Austin ’20, who trained at the Plattsburgh camps and was a member of the ROTC at Harvard. He was killed in action on Nov. 11, 1918, a few hours before the armistice was declared.

During the war, Harvard president A. Lawrence Lowell wrote to the mother of every undergraduate who was killed. He remained haunted by the dead, and wrote 20 years later: “They are gone, and how much may have been lost to the world with them we shall never know, for they were among the choicest of their kind.”

A World War I-related exhibit, “From the Alps to the Ocean: Maps of the Western Front at the Harvard Map Collection,” will run through Nov. 11 at Pusey Library’s Map Gallery Hall.