Harvard Square, looking south, circa 1860, albumen print. At left-center is Farwell’s general store, built around 1800, and to the right, on the site of the present-day Harvard Coop, is Lyceum Hall. In the foreground, barely visible, are the rails of a horse-drawn streetcar line, Union Railway, which opened in 1854.

Photos courtesy of Harvard University Archives

The ‘mirror with a memory’

Photo exhibit spotlights Harvard in the Civil War era

The Harvard University Archives resemble a time machine. Get behind a desk, fill out a form, dial back to the year you want, and there you are: transported by means of collected books, manuscripts, diaries, and more.

Then there is “Mirror With a Memory,” a Pusey Library exhibit of photographs and other artifacts from the years when Harvard and the nation were anticipating the Civil War, then fighting in it (or, in some cases, avoiding the fight), and later remembering it. In four glass cases, the display serves a dual role. It distills what Harvard was like 150 years ago, and it showcases the photography of the day. Writing in the Atlantic Monthly in 1859, Harvard poet and medical professor Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., A.B. 1829, called the new medium, barely 20 years old, “the mirror with a memory.”

The Civil War was not the first conflict to be captured in that mirror, said exhibit curator Juliana Kuipers, a special materials cataloger and processing archivist. But it was the most extensively photographed to then, and the portable images — on glass, copper, iron, and paper — changed the American perspective on war. Photography brought the front home. “You had these battlefield images,” Kuipers said, and soldiers could keep them in pockets and knapsacks, or send them to their families. The photos also served as resonant artifacts of lives lost to war.

The show’s biggest images show the College at that time: dusty Harvard Square, with one horse poised to pull a rail trolley; Harvard Yard, with undergraduates in top hats loitering outside Hollis Hall; and the muddy shore line of the tidal Charles River along Mt. Auburn Street. Memorial Hall is visible on the far northern horizon.

Over the exhibit’s cases, a timeline recounts the history of photography, from the 18th century photograms of Thomas Wedgwood to the 2010 Apple iPhone. (Emily Tordo, a staff assistant at the archives, did the layout.) In between are the photo technologies typical of the Civil War era: the daguerreotype and the tintype, both metal artifacts that were framed and fragile; the ambrotype, made of glass; and the albumen print, the first type of photo printed on paper from a negative. It was the albumen print, reproduced on a substrate of cotton paper, which made photos robust and portable enough to be carried by soldiers or mailed home.

The College’s first class album, in 1852, was simply 83 daguerreotypes stored in a wooden case. The images were the work of Boston photographer John Adams Whipple, the official class photographer until the eve of the war, and inventor of the crystalotype, paper prints created from daguerreotypes.

In the realm of minor photographic inventions with a Harvard provenance, “Mirror With a Memory” includes a mention of the quotable Holmes. He developed a handheld stereoscope for viewing dual photographs so that the images appeared to have depth.

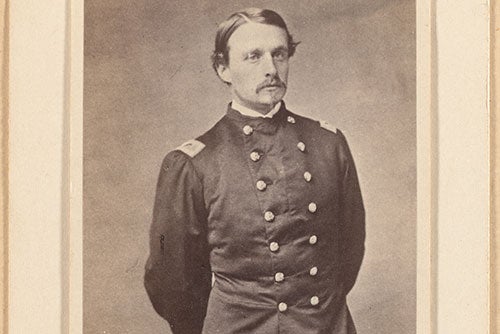

These technologies seem exotically archaic. But the images they created bring the viewer back to the duality of the time machine/archive. The exhibit shows simultaneously what has changed and what has stayed the same. The best example is the striking currency of young men posing for posterity on the eve of war. Robert Gould Shaw, A.B. 1860, whose uniformed image appears twice in the show, looks as impossibly youthful and handsome now, in an albumen print image, as he surely did then. He died in battle in 1863, but we can see him still.

Other faces in the exhibit look roughly contemporary. Longtime Harvard librarian John Langdon Sibley, A.B. 1825, whose 1846-1882 diary records life at Harvard, looks well-fed and professorial. A teenage Robert Todd Lincoln, A.B. 1864, captured in an 1860 ambrotype, was President Abraham Lincoln’s eldest son, and he rode out most of the fighting as an undergraduate. Bearded, tough-looking William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, Confederate general and the second son of Gen. Robert E. Lee, enrolled at Harvard in 1854 and left in his junior year. (His picture is seen in part of one exhibit case nearly given over to Harvard’s Confederate veterans.)

These indoor portraits look like they could have been taken yesterday. But in photos taken outdoors, we return to an irretrievably vanished world. At the juncture of Garden Street and Concord Avenue is a long line of heavy cannon piled in front of the Cambridge Arsenal. In another image, a few uniformed men of the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry — named “the Harvard regiment” for the origin of its officers — stand in front of a log cabin at Fort Benton, Md., in the fall of 1861. They had just survived the 20th’s first battle, at Ball’s Bluff, Va.; 88 of their fellows had been killed or wounded (including future Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.), and 113 captured.

Other exhibit artifacts root us just as firmly in the past. To illustrate the early days of the war, there is a copy of the May 1861 issue of Harvard Magazine, then an undergraduate publication. It is open to an angry letter from Confederate sympathizers in Kentucky, which invites Harvard boys to “smell the powder and feel the steel of Southern gentlemen.”

To illustrate the end of the war, the exhibit looks at Harvard’s efforts at commemoration. There is a list of the Union dead published for Commencement in 1865, an album of images of the slain (there is Shaw again), and documents about Memorial Hall.

The exhibit includes an 1864 letter from Harvard senior Frank Waldo Wildes, A.B. 1864, to classmate John Owen, A.B. 1864. Wildes was getting ready for Class Day. Owen was at the front, an officer with the 36th U.S. Colored Troops.

“You say you are very busy,” said Wildes, showing a touch of heat. “Well, so am I.”

“Mirror With a Memory” is on view at the Harvard University Archives, Pusey Library, through June 5. Hours are 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday.