Harvard President Drew Faust visited the Keio Girls Senior High School during a 2010 trip to Tokyo and later China. “Universities exchange faculty and students as never before, and engage in an increasingly porous world of international problem solving and collaboration,” Faust said at the opening of the Harvard Center Shanghai.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Writer

Harvard-Asia: Ties deep and broad

Faust’s upcoming visit is framed against University’s longstanding involvement with continent

First in a series about Harvard’s deep connections with Asia.

On April 11, 1925, a portable phonograph began blaring the Italian opera “Rigoletto” through the dusty village of Ch’ing-shui, China, prompting curious listeners to pour into the streets and onto nearby rooftops.

Botanist Joseph Rock had brought the phonograph on his three-year collecting expedition for Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum and the Museum of Comparative Zoology. In mounting his simple concert, Rock was adding in a small way to Harvard’s nascent educational exchange with Asia, which had begun in 1879 when scholar Ko K’un-hua became the first instructor to teach Chinese at Harvard.

Over the last century, the connections between Harvard and Asia have grown from such early trickles to a broad torrent of ideas, information, and people. Harvard now exchanges students and scholars with dozens of Asian nations, including three of the world’s four most populous: China, India, and Indonesia. Harvard conducts research across Asia into energy, business, health, government, history, art, and culture. The University also offers its expertise to everyone from farmers in Myanmar to Khmer Rouge justice-seekers in Cambodia to fledgling democratic leaders in Indonesia.

To encourage this exchange, Harvard maintains several offices in the region, including posts in Mumbai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, and Shanghai. The University leans on and, in turn, supports local partners at a host of Asian institutions. And in collections that delight the public even as they enlighten scholars from around the world, Harvard also is a careful steward of thousands of items from Asia that are of historic importance, radiant beauty, and natural wonder.

‘World of universities without borders’

This Harvard-Asia exchange now is part of the endlessly evolving knowledge economy, where information — global and nearly instantaneous — drives economic growth and in which universities play pivotal roles. Rock and Ko planted seeds not only for the knowledge economy but also for what Harvard President Drew Faust described during a 2010 speech in Shanghai as a “world of universities without borders.”

“Universities exchange faculty and students as never before, and engage in an increasingly porous world of international problem-solving and collaboration,” Faust said in the speech, which marked the opening of the new Harvard Center Shanghai. “Higher education is developing a global meritocracy.”

Asian nations today, led by the global titans China and India, are roaring ahead, gaining importance both economically and politically. Likewise, Harvard’s engagement with Asia has grown rapidly in recent decades. The emergence of China and India as global economic titans has only increased the attraction of countries whose ancient civilizations, art, music, and culture have long made them objects of fascination for scholars in many fields.

“I’ve always felt that globalization is upon us and many countries in Asia were going to emerge very strongly,” said Venkatesh Narayanamurti, former dean of Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and Peirce Professor of Technology and Public Policy, who has had partnerships with Indian institutions in Mumbai and Bangalore.

Harvard’s recent venture into online education, edX, has diminished borders even further. Students from Asia and elsewhere around the world have gained increased access to courses at Harvard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and other universities. Though it launched its first course just last fall, edX already has drawn 677,000 students, 40 percent from outside the United States.

In March, Faust will deepen her own engagement with the region (which already has included trips to Japan, India, and China) during a spring break trip to South Korea and Hong Kong. There, she’ll visit with alumni groups, deliver a speech to students of Ewha Women’s University, and spend time with current Harvard students visiting Ewha.

Faculty members have played important roles over the decades in building bridges between Harvard and Asia, fostering not only teaching and learning at Harvard but also understanding more broadly among the United States, Japan, and China.

For instance, Edwin Reischauer pioneered Japanese studies at a time when both knowledge and interest in the country were lacking. He became ambassador to Japan under President John Kennedy, and today is the namesake for Harvard’s Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies. John Fairbank was widely known for his scholarship on China and also has a research institute here named for him, the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. Fairbank’s legacy extends through the scholars he trained who went on to teach others.

“Fairbank really deserves enormous credit for not only sustaining and nurturing the study of China at Harvard, but, through his students, creating a scholarly basis for the study of China in the U.S.,” said Jorge Dominguez, Harvard’s vice provost for international affairs.

Likely to have been born in those regions

Harvard scholars of particular regions today are as likely to have been born in those regions as not. In its search for academic excellence, Harvard recruits faculty members around the world and, once they are here, takes advantage of not just their academic skills but their leadership talents, as illustrated by Nitin Nohria’s tenure as dean of Harvard Business School (HBS) and Xiao-Li Meng’s as dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS).

International students have become a far larger part of Harvard’s student body. The Harvard International Office, founded in 1944 to help foreign students with the transition to the University’s various campuses, teaching hospitals, and research institutions, began with just 250 students and scholars. Today it serves more than 7,000.

China, with 686 students, has the largest non-U.S. student contingent at Harvard. Of the top 10 countries that send students to Harvard, five are from Asia, including South Korea, third overall; India at fourth; Singapore at seventh; and Japan, which is 10th.

Once here, students can select from hundreds of classes on Asia-related topics ranging from language instruction to religion to history, from governance to business to global health, from art to energy to engineering to a host of others.

Most other Harvard students don’t stay put for their entire academic careers, either. Harvard students travel abroad with increasing frequency, with China the most popular destination by far, according to Dominguez.

Research opportunities are numerous and are supported by several regional centers and institutes that cover Asia and South Asia, including China, through the Fairbank Center, Japan, through the Reischauer Institute, and Korea, through the Korea Institute. Chinese studies are fostered further through the China Fund, an academic venture effort that promotes research on topics important to the nation. These regional programs can help to coordinate work from researchers across the University. In January, for example, the South Asia Institute (SAI) spearheaded a cross-disciplinary, University-wide effort to visit and conduct research at India’s Kumbh Mela, a religious gathering that occurs only every 12 years.

Perhaps the grandfather of such efforts at American universities also resides on Harvard’s campus: the Harvard-Yenching Institute. Founded in 1928 as an independent foundation with close ties to Harvard, the institute was begun in collaboration with Yenching University and several other Chinese colleges that were closed by the government in the 1950s. The Institute at Harvard survived closing by broadening its attention to other East Asian countries before again including China after it reopened to the United States in 1979.

Today the Institute, whose Harvard-run library has the most East Asian materials of any university outside East Asia, sponsors some 50 scholars from Asia to study at Harvard each year. The institute is headed by a Harvard faculty member, Rosovsky Professor of Government Elizabeth Perry, and also supports faculty and advanced graduate research and training programs, both at Harvard and at its 50 partner universities in Asia.

“China is one of the world’s great civilizations and today boasts the second-largest economy in the world, in terms of importance and status,” Perry said. “It’s absolutely important, critical that students have the opportunity to learn about China and about East Asia more broadly.”

Significant exchange of material

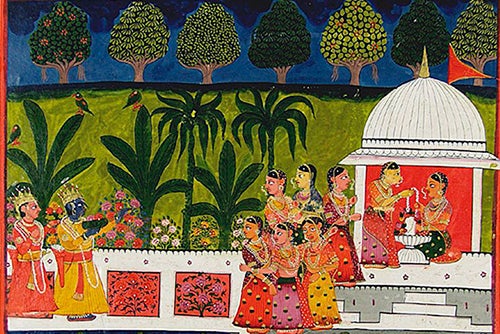

In addition to the exchange of knowledge between Harvard and the countries of Asia, a significant amount of material has also been exchanged. Across Harvard, in museums and collections, thousands of objects from Asian nations delight viewers when put on display and enlighten researchers who study the collections.

Those collections extend beyond the arts to science. The fruits of Rock’s three-year collecting trip are still available to scholars nearly 90 years later, in the dried plant collections at the Harvard University Herbaria, the prepared bird skins at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, and at the Arnold Arboretum, where the living specimens Rock brought back — butterfly bushes, cotoneasters, and dragon spruce among them — still grow and fruit each fall. Rock would return to China, working there while a research associate and fellow with the Harvard-Yenching Institute in the 1940s.

The Arboretum itself is something of an East Asian botanical stronghold, and in it Harvard’s commitment to Asia literally grows each year. The Arboretum is a living collection of tree and shrub specimens from around the world, with an emphasis on the United States and East Asia. In fact, specimens from China, Japan, and South Korea together outnumber U.S. specimens more than 2,800 to 2,094 — a slice of East Asia in Boston’s Emerald Necklace.

To read more Asia coverage, visit Global Harvard.