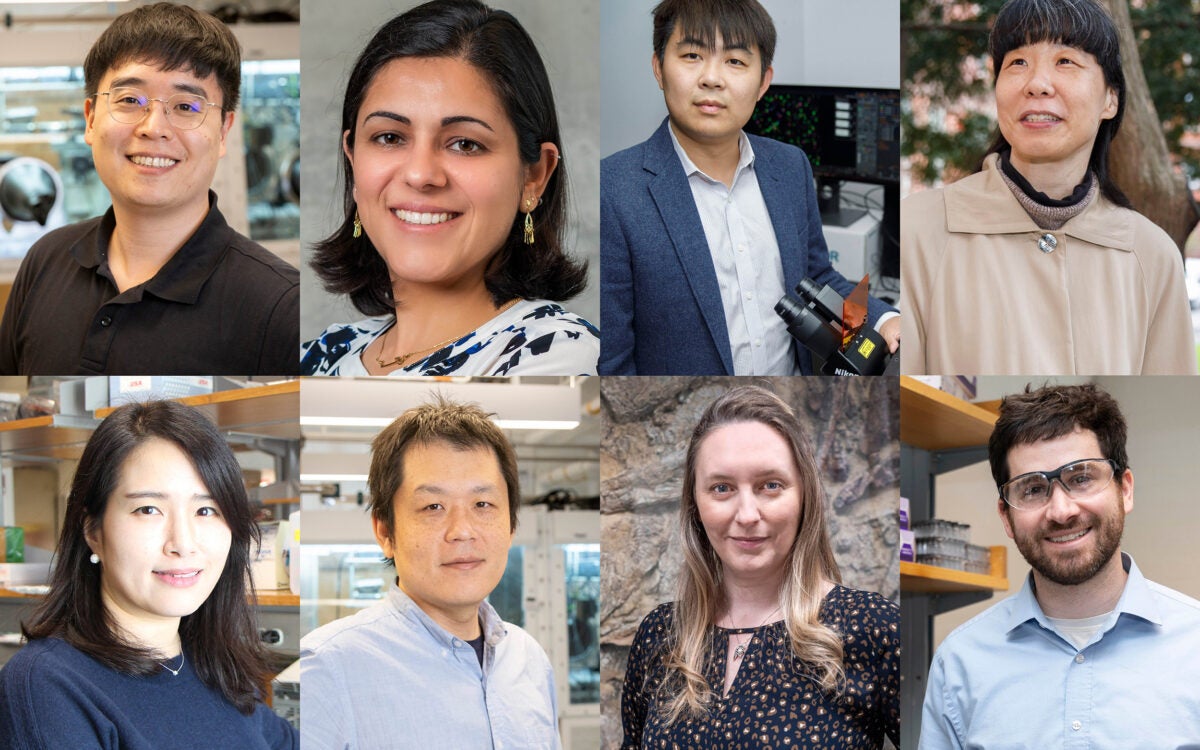

Harvard affiliates Kara Oehler (from left), Jesse Shapins, and James Burns have won the Knight News Challenge, a fiercely competitive international contest, and will use the funding to develop a prototype software called Zeega, an open-source web platform designed to make collaborative multimedia documentaries cheaper and easier to produce.

Justin Ide/Harvard Staff Photographer

From A to Zeega

Harvard team wins prize for multimedia software

Three Harvard affiliates — two fellows and a graduate student — have won the Knight News Challenge, a fiercely competitive international contest that funds digital news experiments that use technology “to inform and engage communities.”

There were 16 prizewinning projects selected from 2,500 submissions. The awards were announced today (June 23).

Contestants from Harvard have won a few times during the five-year life of the Knight contest, but never for as much money — a grant worth $420,000, said Colin Maclay, managing director of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society. The competition is “insane,” he added. “Getting into Harvard College has nothing on this.”

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, which sponsors the competition, calls its winners “journalism futurists.” They are described as thinkers and designers who employ emerging technologies to make citizen journalism more accessible, compelling, and intellectually rich.

Starting Sept. 1, the three Harvard team members, who were Knight finalists last year, will use their 18-month funding to develop a prototype software called Zeega. The open-source web tools will be designed to foster new genres of investigative journalism and media art, making collaborative multimedia documentaries cheaper and easier to produce.

The Knight project “grows out of a unique combination of documentary arts and experimental media research we’ve been doing within Harvard and beyond,” said Jesse Shapins, one of the three winners. He is a Ph.D. student in Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, where he also lectures in architecture.

James Burns, who graduated in May with a Harvard Ph.D. in economics, is a creative technologist and relational knowledge fellow at the metaLAB (at) Harvard. Shapins and Burns worked together on courses such as Media Archaeology of Place and The Mixed-Reality City, which have used test versions of Zeega, with support from the Presidential Instructional Technology Fellows program.

Kara Oehler, an independent journalist and 2011-12 Radcliffe-Film Study Center Fellow, also co-founded metaLAB and is a fellow there.

Shapins, Burns and Oehler started working together in 2008 while developing Mapping Main Street, a project that aims to document all of the streets named Main in the country. Created with radio producer Ann Heppermann, the project combined a series of audio documentaries broadcast on National Public Radio with a web platform that automatically interrelates media about Main Streets that was contributed by citizens into thematic and geographic pathways. Last year, the project was presented to the Federal Communications Commission as a leading example of innovative approaches to storytelling, during a symposium on the future of media. Working on the project also gave the three inspiration to create Zeega, which they hope will provide a user-friendly framework for creating online documentaries that are layered, interactive, and multifaceted.

Shapins, Burns, and Oehler embody what they described as a convergence of creative forces in the area and at Harvard, which are moving vigorously to merge digital practices with journalism and traditional scholarship.

At Harvard, they said the signs of that convergence include the metaLAB; the Berkman Center; Sensate, a multimedia online journal launched this spring; the annual Harvard Film Study Center fellows (Oehler will be one in 2011-2012); The Lab at Harvard, a space for experiments in art and science; the Sensory Ethnography Lab, with its creative interdisciplinary ethic; the Harvard Library Lab; and the new “critical media practice” secondary field approved this year by the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. That will allow Ph.D. students for the first time to incorporate film, video, photography, and other forms of nontextual information into their academic work.

“It’s really an incredible time for technology and new forms of journalism and scholarship at Harvard,” said Oehler.

Part of the convergence involves the Boston area itself, the prizewinners said. For instance, Cambridge is home to the collaborative Public Radio Exchange. In Dorchester, there is the Association of Independents in Radio (AIR), which funded Mapping Main Street.

The three prizewinners feel right at home amidst this convergence of media innovation. After all, they were media rebels at an early age.

In the early 1990s, Shapins and Burns were eighth-grade classmates in Boulder, Colo., when an early media experiment earned them trouble instead of a prize. Distributing their first issue of “The Bricks are Red,” a zine pieced together on vintage Macs, got them a day of in-school suspension. (“Interestingly,” said Burns, “they put us in a room together. So we worked on the next issue.”)

In a pre-digital age, zines were self-published magazines with alternative viewpoints, low circulations, and no plans to make money.

Around the same time, Oehler, who was an Indiana middle school student, was suspended for the same reason. Her offending publication was “The Alternative Maggot,” whose rebellious yet clever staffers were forced to eat lunch in the chemistry lab for a month.

After graduating from college in 2000, Oehler was still drawn to media experimentation and started a career as an independent producer for public radio. In 2005, while concentrating on interactive documentaries, she was struck by the technological inequities of production. Large media outlets had the money to do what they wanted in making multimedia documentaries. But independent journalists and small, cash-poor stations and websites were often shut out of Internet age technologies.

Even today, “there’s this huge digital divide,” said Oehler. “The idea of Zeega is to bridge that gap.” As early as the fall of 2012 — after six or seven pilot projects, refinements by software contractors, and a beta launch — Zeega will be available free, and aims to make interactive documentaries as easy to incorporate into web sites and mobile applications as YouTube videos.

After that, “anyone can go and start creating,” said Burns, a self-taught programmer who will lead the project’s technical team. He described Zeega’s present state as “very experimental.” But the Knight grant will provide the resources to refine it, test it, and make it “scalable,” available to a wide audience.

Once an accessible platform is available for making these interactive projects in small markets, Oehler predicted, “we’ll see a huge change. It will allow anyone to create a project like Mapping Main Street.”

Mapping Main Street itself has already been crowd-expanded, said Shapins. The original project documented 100 of the 10,466 streets named “Main” in the United States. But now the site, thanks to outside collaborators, provides views of 800.

During her Radcliffe year, Oehler will focus on developing Zeega through a new audio and interactive documentary show that immerses audiences in the particularity of places, while interweaving the ambiguities and surprising pathways that emerge during the documentary process. The show will combine aesthetic experimentation with ethnographic approaches to engage major news topics through everyday examples, creating a new space for artistic invention on the airwaves and on line. To begin, she has summer road trips planned to Montana, Texas, Louisiana, West Virginia, and elsewhere to record stories.

Once public, Zeega will be an open-source platform, said Burns, meaning that the code will be available to refine or alter for other applications. Concurrently, he added, the original Zeega will be software-hosted, in the same way YouTube is hosted.

Zeega is housed in Media and Place (MAP) Productions, an independent 5013c nonprofit that is overseen by the three.

Meanwhile, the technology divide still exists. For a time, Oehler herself lived that truth. In the summer of 2009 she moved out of her house, put her possessions in storage, and set off on a 14,000-mile, 100-city tour of the United States to document Main Streets for National Public Radio. Her nightly guest room was a Subaru Legacy. (“The seats fold down,” said Oehler.) Along for the ride, at intervals, were Shapins, Burns, and radio producer Ann Heppermann.

In the future, however, Zeega should make things easier for journalists and documentarians, said Oehler. “You shouldn’t have to give up your house to make interactive documentaries.”

In academia, Zeega will give scholars the same sense of agency it imparts to journalists, said Burns, who added that Harvard is already experimenting with “new forms of scholarship, including publications that are not text-bound.” The name Zeega is appropriate for such an endeavor. It is derived from Dziga Vertov, the pioneering Soviet filmmaker who reinvented the format of the newsreel to incorporate radical new aesthetic approaches and collaborative methods, exemplified in works such as the 1927 “Man with a Movie Camera.” The Harvard Film Archive has one of the largest collections of Vertov prints, to which Shapins was exposed while taking a course on Vertov’s work his first year as a PhD student.

Zeega also should give scholars another tool for collecting media from now-largely untapped resources, including artifacts, films, photos, and other media that when streamed together enlarge views of culture, history, and society. Burns called it “depth of knowledge.”

This dimension is already being explored through the metaLAB and Frances Loeb Library project extraMUROS, which builds on top of Zeega and is funded through the Harvard Library Lab.

Zeega, digital humanities, an energized community of documentarians, and now the Knight Prize, said Shapins: “It’s all part of this magic moment at Harvard.”