“FAX,” a traveling art exhibit on view through April 10 at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, includes a piece by Peter Coffin, “Untitled,” 2009.

Courtesy of the Carpenter Center

Just the fax

Transmission takes a turn as art

Most of us associate the word “fax” with that big machine that sits — largely unused — in the corner of the office. A device for sending documents over a phone line, it seems to belong to an era when cell phones were the size of walkie-talkies.

Indeed, the machine’s mechanical and chemical antecedents go all the way back to 1843, and the first wireless transmission of a photo facsimile was sent from New York to London in 1924. (A picture of President Calvin Coolidge.)

Now there is a very modern twist to an old technology: “FAX,” a traveling art exhibit on view through April 10 at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. The idea — first executed two years ago at The Drawing Center in New York, and still co-organized from there — is to invite artists and others to use the fax machine to marry the art of the hand with the foibles of electronic transmission.

The work, beamed to a fax machine in the gallery, is posted on the walls. And all the while the show is up, faxes still roll into the exhibition space from scientists, architects, filmmakers, painters, and others. This is art on the fly, and shows off the humble fax as an artistic medium that is still largely untapped, despite experimentation that started four decades ago.

The Carpenter Center show also revives some of the early rebellion of the fax, a fluid, democratized defiance of convention that now seems to reside wholly on the Internet. After all, the technology that started as a mainstay of business was also soon a medium for subversion, urban legend, and humor — the “faxlore” of office spoofs, crude jokes, and even transmissible body parts. (Ever see a squashed bum on paper? Of course.)

The fax was a foreshadowing of Twitter and YouTube, said Joao Ribas, creator and curator of the original “FAX” exhibit in New York, and it represents the beginning of when artists got the tools to create communication networks.

The show itself becomes a “network of collaboration in experimental time,” said Ribas, who is now curator at the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Earlier this month, he led a scrum of viewers on a tour of the latest iteration of “FAX,” which is co-organized by Independent Curators International.

Multiple faxes from multiple contributors in multiple shows create a cumulative exhibit, and there’s no end in sight. “FAX” has already been on display in New York, Paris, Hong Kong, and elsewhere — with each show having its own invited list of up to 20 contributors. The faxed work, whimsical and weird, is posted on exhibit walls or filed in thick binders for viewers to peruse.

As Ribas spoke, someone was just getting over the hiccups. Not a bad analogy for fax art though. The medium requires capricious airwaves, and a receptor technology that occasionally stutters, smears, or streaks the finished product.

Leave it in, said Ribas. The caprice of the fax itself is part of the fun. “We wanted the machine,” he said, “to become a collaborator.”

Painter and printmaker Tauba Auerbach was invited to contribute to the Harvard iteration of “FAX,” so she called Ribas and said she wanted to stop by and listen to the fax machine. While he sent faxes from across the street, she stayed in his MIT office “listening to it as an instrument,” he said. The result is a six-panel array, “What a Fax Says,” converting into letters and punctuation the familiar electronic noise the machine makes — a symphony of brrringgg!!! and purrrrr….

“The fax machine is kind of this dumb thing in the room,” said Ribas, but it is also “essentially a printmaking machine” — an art medium that began when art did, with rubbings. It is also a machine that people treat as a camera, he said, or appropriate for a kind of “collage sensibility” suggestive of early Dada.

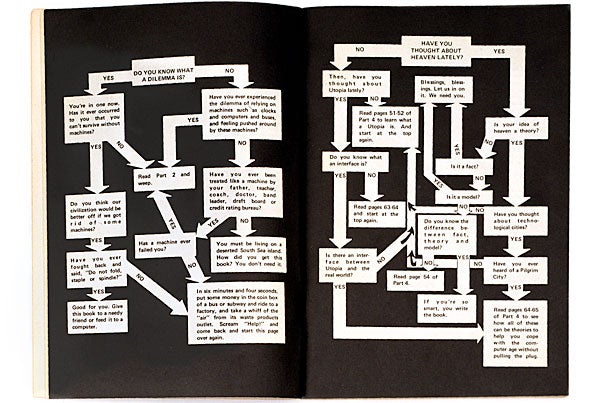

Then there is the plebian heritage of the fax itself — the opportunity to be zany, and spread it around. So in the show you will find a faxed detail, courtesy of Cabinet magazine, from “spaghetti junction” by Ernst Falzeder. It’s part of his “family tree of psychoanalysts and their patients,” the card reads. Look for the circuitry of influences that connect Hermann Hesse, Jean Piaget, William Burroughs, Wilhelm Reich, and boxed names ending with “Freud,” including Oliver, Ernst, and Anna.

In the archived faxes, gathered in three-ring binders, there is art worth looking at, too, including a series of closely edited press releases — along with faxed responses. And look for the faxed Ronald Reagan doodles, the faux eye chart (WTF, OMG, etc.), a faxed Post-it note conversation, and — yes — instructions on how to fax a smoke signal.

“FAX,” being the creation of defiant creators, also includes at least one example of pure defiance. Boston artist Andrew Witkin was invited to send a fax to the show. He thought it over, typed a message out on yellow paper, made his corrections in Wite-Out, and hand-delivered it.