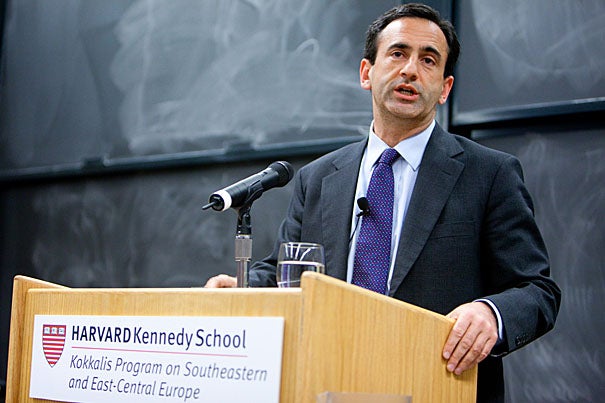

Phillip H. Gordon, the U.S. assistant secretary for the Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, told an audience in the Goodman Classroom that “the political and economic integration” of Southeastern Europe within the rest of the continent is the key to regional stabilization and development in the years ahead.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Knitting Europe together

Obama aide hopes to draw southeastern states into continental structures

The Obama administration seeks a “path to a better way” for the nations of southeastern Europe, and a top administration official laid out the components of that strategy during a talk on Wednesday (Feb. 17) sponsored by Harvard Kennedy School’s Kokkalis Program on Southeastern and East-Central Europe.

Phillip H. Gordon, U.S. assistant secretary for the Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, told an audience in the Goodman Classroom that “the political and economic integration” of southeastern Europe within the rest of the continent is the key to regional stabilization and development in the years ahead.

“We have a vision of a peaceful and stable Europe that will extend to Turkey and the Caucasus,” he said. “The solution lies in transnational cooperation and institutions that guarantee the rights of citizens, promote economic freedom, insure the viability of the border, and provide a reliable forum for the peaceful resolution of disputes.”

Gordon pointed to the critical importance of regional and international institutions in this effort, specifically NATO and the European Union. Several southeastern European countries are now members of the EU, including Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania, and several belong to NATO, including Albania, Croatia, and Turkey. Other nations are seeking entry into one or both organizations.

“The opportunity for political engagement that crosses national borders reduces the salience and pressure of ethnic and regional disputes within countries. That is the promise of the project of European integration,” Gordon said.

Recent decades have brought tremendous change to the region, Gordon added, and the United States is now developing close and productive relations with several nations in the area, including Serbia, which was beset by violence and instability as recently as a decade ago.

“I certainly believe … that with pragmatism and goodwill on both sides, U.S.-Serbian relations could be a model of a productive partnership by the end of the administration’s first term,” Gordon said. “This change in the Balkans is a reminder not only of what can be possible, but also what remains to be done” elsewhere.

Kosovo is another example of a “remarkable story of progress” in the Balkans, Gordon said, although he admitted the country faces serious challenges that will require a “great deal of work” moving forward.

Gordon also pointed to the critical roles that Greece and Turkey will play in helping stabilize southeastern Europe, arguing that “regional political leadership and courage and vision is necessary for progress.”

In his concluding remarks, Gordon cited the fact that “some of the same fault lines” that have plagued the region for many years still remain, but that he is hopeful there is a “clear potential solution” in the full economic and political integration of the southeastern states within greater Europe.

Gordon was introduced at the podium by Elaine Papoulias, director of the Kokkalis Program. About 100 people attended the lecture.