Professor Nicholas Christakis delivered the 2011 Opening Days Lecture, telling freshmen that human social networks have the power to spread obesity — or happiness — like contagion.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Connecting with freshmen

Opening Days lecture highlights power of social networks

Harvard College freshmen got their first taste Aug. 26 of the world of ideas awaiting them over the next four years in a talk by Professor Nicholas Christakis, who argued that human social networks have the power to spread obesity — or happiness — like contagion.

Christakis, who teaches at Harvard Medical School as well as the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, delivered the 2011 Opening Days Lecture, “Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives.” He told students at the outset that his work is not primarily concerned with online social networks, but instead focuses on “old-fashioned, face-to-face” relationships and their construction and meaning in people’s lives. A “bucket brigade,” for example, is a network of individuals optimized to perform a task in pursuit of a goal: the transport of water to extinguish a fire. Take the same network and organize it in a different way, and it will be optimized for a different purpose: a telephone tree to disseminate information; a Ponzi scheme for the profit of grifters.

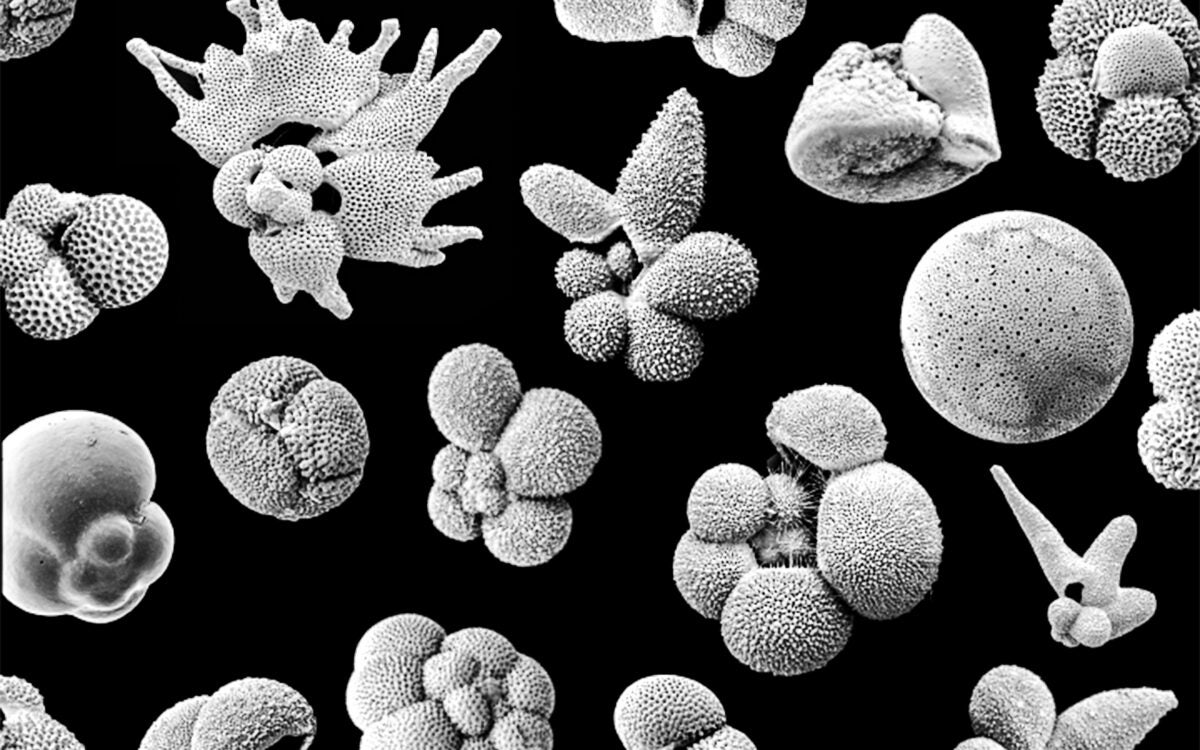

Christakis, who is a medical doctor as well as a Ph.D., discussed his interest in the impact of human social networks on public health. In 2002, he and some colleagues studied the problem of obesity, often called an “epidemic” in Western society. Christakis said he wanted to examine social networks to see whether or not obesity actually spreads from person to person, like a virus. He showed students graphs of data from the 30-year Framingham Heart Study, and explained how he and his colleagues analyzed clusters to see if someone were more likely to become obese if a friend were overweight.

“We found that, if your friend is obese, there is a 45 percent greater likelihood that you will become obese,” he said. “If your friend’s friend is obese, the likelihood is 25 percent higher. In fact, only at four degrees of separation — your friend’s friend’s friend’s friend— is there no longer a relationship between that person’s body size and yours.”

Christakis said that he and his colleagues found that human social networks could also move public health in a positive direction. For example, since 1971, the proportion of the U.S. population that smokes tobacco went from 40 percent to 20. Christakis again displayed data from the Framingham study that showed people typically quit smoking in clusters. A person was more likely to stop using tobacco if his or her friend — or even a friend’s friend — stopped.

The study of networks and happiness gave Christakis his greatest personal satisfaction, he said, and allowed him to settle an old debate.

“In high school, [my friends and I] would tell our mothers, ‘If I could just be more popular, then I would be more happy,’ ’’ he said. “Our mothers would say, ‘Actually, if you become more happy, then you’d be more popular.’ It turns out that we were right, and our mothers were wrong! Being in the middle of a network enhances your happiness. If you become more popular, that contributes to being happy more than being happy contributes to being more popular.”

Toward the end of his talk, Christakis did turn to the differences between online and traditional networks. In a study of Harvard undergraduates on Facebook, he found that students had an average of about 110 “friends.” To see how many of these relationships were close and how many tenuous, he had some students look at Facebook profiles to see how often classmates uploaded and tagged photographs of people they were connected to online. The findings reinforced the value of relationships based on traditional face-to-face contact.

“You might have 1,000 friends on Facebook, but only for a subset of them do you appear in a photograph that gets uploaded and tagged with your name,” Christakis explained. “Based on this, we found that people typically had over 100 Facebook friends, but only six real friends [who uploaded and tagged their photo].”

In light of these results, Christakis expressed concern about the way that Facebook had changed the meaning of the word “friend.”

“It’s very interesting to me that Facebook has managed to co-opt a very old word in our language — friend — and apply it where it has no business,” he said. “All those people, they’re not your friends. At best, they’re your acquaintances.”

Judging from the applause, the talk was a hit with freshmen. Constantinos Tarabanis ’15 said that he’d heard a speech that Christakis gave in Greece not long ago and wanted to learn more about human social networks.

“I like what he said about the dispute he had with his mother and that being in the center of a network made you happy,” he said. “The way he explains difficult ideas in simple terms was pretty amazing.”

Domniki Georgopoulou ’15 said that the lecture made her eager for the beginning of the school year.

“I’m going to study sociology,” she said. “I’m already looking forward to classes.”