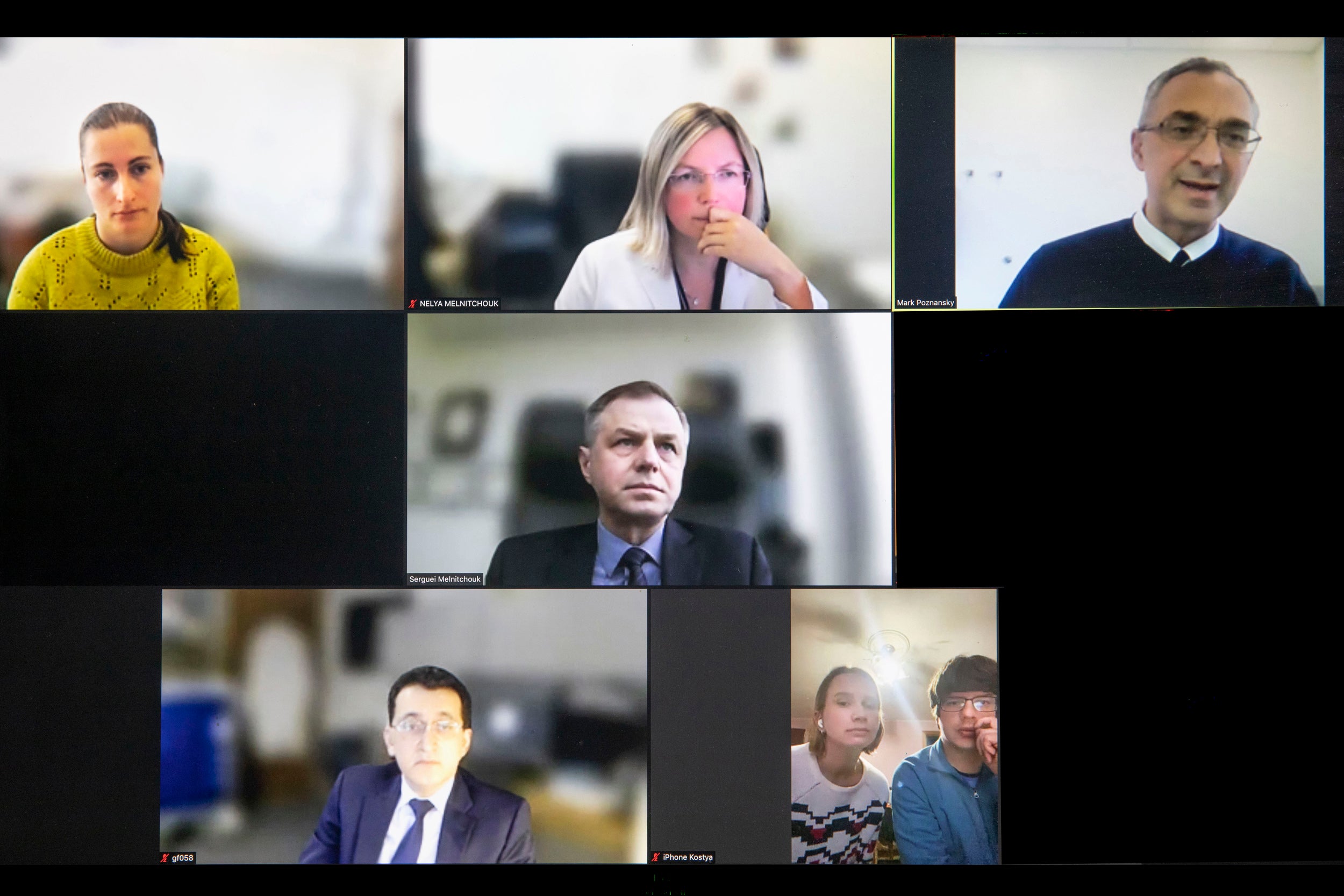

Physicians Polina Teslyar (clockwise from left), Nelya Melnitchouk, Mark Poznansky, Serguei Melnitchouk, Dana Ronak and Rolin Kostya, and Gennadiy Fuzaylov speak with Harvard-affiliated doctors from Brigham and Women’s and MGH via Zoom to discuss the situation in Ukraine.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Viewing Ukraine’s war-torn health care through a personal lens

HMS physicians share personal stories, assistance efforts

Both Serguei Melnitchouk and his wife, Nelya, are surgeons, he at Massachusetts General Hospital and she at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Both are Harvard Medical School assistant professors, and both have families who are safe for now in small towns in Ukraine.

“We are constantly checking the news and trying to find ways to help,” said Nelya, who directs the Brigham’s colorectal surgery fellowship and is working with her husband on a series of medical aid projects for Ukraine. “Obviously, this whole war is very close to my heart.”

The Melnitchouks shared their story and experiences on Tuesday during an online gathering of medical personnel from HMS and its affiliated hospitals, which drew more than 140 to the noontime session.

Since Russia’s invasion on Feb. 24, the pair have been marshaling resources here to help over there. They had created a nonprofit, the Global Medical Knowledge Alliance, which provided practical physician-education materials that were translated into Ukrainian and Russian. The war kicked their efforts into high gear, and their team of 15 volunteers is pressing to translate the American College of Surgeons’ Advanced Trauma Life Support Manual, which would provide help dealing with the kinds of wounds local physicians might see on a battlefield or the streets of a city under siege.

They’ve also recorded instructional videos, some aimed at physicians and others at laypeople, about how to stop bleeding, do a chest tube insertion, and keep safe in the event of chemical, biological, or nuclear attack. They’ve gathered and sent trauma packs with tourniquets, surgical staples, needles, nasopharyngeal tubes, endotracheal tubes, and other supplies. The packs are carried by people traveling to Poland, picked up there, and transported into Ukraine, where they are brought to health care facilities.

Mark Poznansky, a professor of medicine at HMS and director of the Vaccine and Immunotherapy Center at MGH, helped organize the event, and said in introductory remarks that it may be the first of a series of regular gatherings intended to share knowledge and update community members about each other’s efforts. Poznansky said his own family left Poland before World War II, and that nation’s experiences made him recognize the horrible, far-reaching costs of war. Some 65,000 Poles lost their lives in the initial invasion by then-allied Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. By the conflict’s end, more than 5 million were dead, including 3 million Jews.

Poznansky said the event is intended as a first step, and that the larger challenge is not to wait until the fighting stops, but to support restoring and rebuilding Ukraine’s health care system even as it is being severely damaged, so that it continues to serve people in need.

“This is about restoring health care while it is under attack,” Poznansky said.

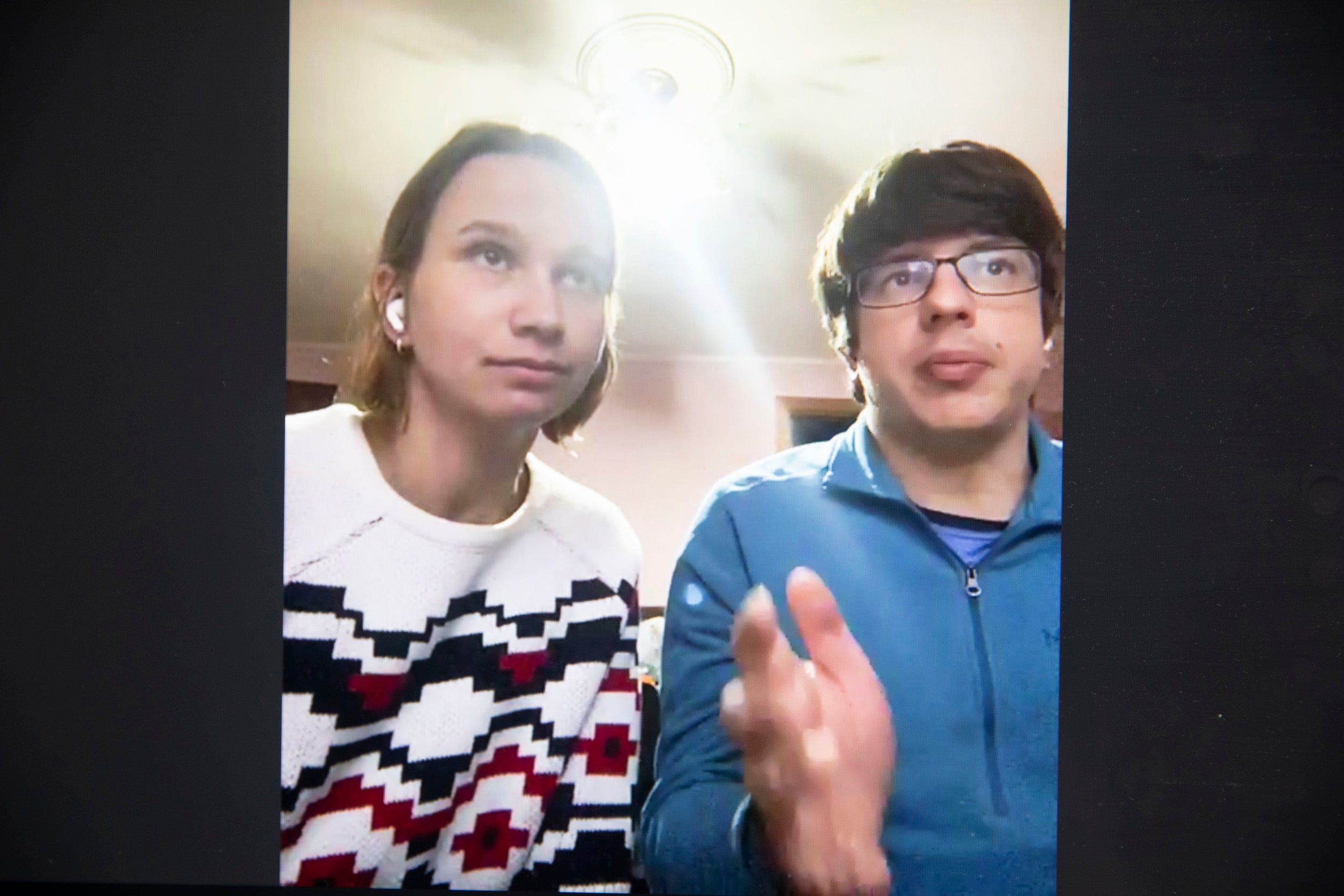

Dana Ronak (left) and Rolin Kostya are currently located in Ukraine.

Other speakers included a couple, Ukrainian physician Dana Rumak and husband Rolin Kostya, who called in from Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine. They detailed shortages in medical supplies in and around Kyiv, including a recent report that Russian troops had looted hospitals on their retreat from towns outside the city. They also noted that a nearby factory has recently started production of medical supplies. The couple said they had lived in Bucha — the city where the bodies of hundreds of civilians have been found in the streets after the recent retreat by Russian soldiers — and that one of their biggest uncertainties is how much of Ukraine will be destroyed before the fighting ends.

Gennadiy Fuzaylov, an assistant professor of anesthesia at HMS and MGH, said that he and colleagues, including those at other institutions like Shriners Hospitals, have collected and shipped five containers of medical supplies since the war began to Dnipro, one of Ukraine’s largest cities, southeast of Kyiv. They also sent 16 water filtration units after Dnipro’s water treatment infrastructure was damaged

Fuzaylov has run a program to improve burn care in Ukraine since 2005, when the group brought to the U.S. a 5-year-old girl burned over 85 percent of her body. Fuzaylov said the girl survived and is now 23. He continued to help after that, and in 2011 he and colleagues created a nonprofit called Doctors Collaborating to Help Children, which brings youngsters needing treatment they can’t get in Ukraine to the U.S. for care.

Polina Teslyar, an instructor in psychiatry at HMS and the Brigham, arrived in the U.S. from Ukraine when she was 7, and has family living in Lviv, a major city in western Ukraine near the Polish border.

“This is a very personal and scary time,” Teslyar said. “I’m a descendant of survivors of the Holocaust, so there is a lot of re-traumatization going on. What we’re seeing looks a lot like images from the ’40s.”

Lviv, which has a population a little bigger than Boston’s, is hosting another 300,000 people displaced by the war. Teslyar has relatives who’ve pitched in on the effort, including an aunt who was a yoga instructor and is now managing logistics around Lviv and a 20-year-old cousin who was a college student but is now an army medic.

They’ve been in daily contact, Teslyar said, and the family reaches out through its Boston-area network to procure and send whatever is in short supply, from tourniquets to bulletproof ambulances.

“It started with, ‘We need tourniquets and IV poles and IV bags and insulin,’” Teslyar said, “And then the asks got a little bit bigger, like heat-signature-reading drones so medics can look for survivors in bombed-out areas without being fired on themselves — that was not so hard to get — and then it was things like bulletproof ambulances, which are harder, and more recently they’ve been asking for things like portable ventilators.”