Harvard Medical School Associate Professor Thomas Deisboeck wants to use his talent for cartooning to help patients better understand medical conditions, and improve things like vaccine uptake.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Do we need to draw you a picture? Yes, or maybe a satiric cartoon

MGH scholars say pandemic showed need for new ways to make public health messaging more persuasive

The cartoon showed a COVID vaccine syringe in the form of a gun held against a recipient’s head. It listed those not responsible if the vaccine — hastily researched and manufactured — went awry: drugmakers, doctors, the government. Then it asked who’s “irresponsible” if they don’t get the shot: You.

Joe Betancourt thought: What a great cartoon.

Betancourt is no antivaxxer. In fact, he’s pretty much the opposite. He’s an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, senior vice president for equity and community health at Massachusetts General Hospital, and founder of MGH’s Disparities Solutions Center. But he knows an effective post when he sees one, even if he disagrees with its message, and thinks it’s time for more persuasive public health communications.

“This is an example of a simple message,” Betancourt said. “Nobody can guarantee anything. Nobody assumes responsibility for what’s going to happen with the vaccine, but if you don’t get it, you’re responsible. That’s a very powerful message, the creativity makes the message.”

The post catches viewers’ attention. It provokes emotion, anger even, at a perceived injustice. That kind of visceral reaction and mobilizing impact is all too rare a result of health communications today, Betancourt says, and the shortcoming has been apparent as coordinated efforts to deal with the global pandemic rolled out in real time.

And he is not alone in this opinion.

Thomas Deisboeck, an HMS associate professor of radiology and associate in neuroscience at MGH’s Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, helped organize a virtual exploratory seminar last spring at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study to jump-start a conversation around innovating in health communications. The gathering drew about two dozen experts in health care, art, and technology, including Betancourt.

“Anything that improves the information transfer, that makes it bidirectional and not just a download from a doctor to a patient, is worth exploring,” Deisboeck said. “Let’s think of visual communication strategies that are beyond the ‘Let’s come up with a cooler Powerpoint template.’ What can we learn from illustration? From visual narratives and animation? From the methods and techniques in comics, from illustrations in children’s books?”

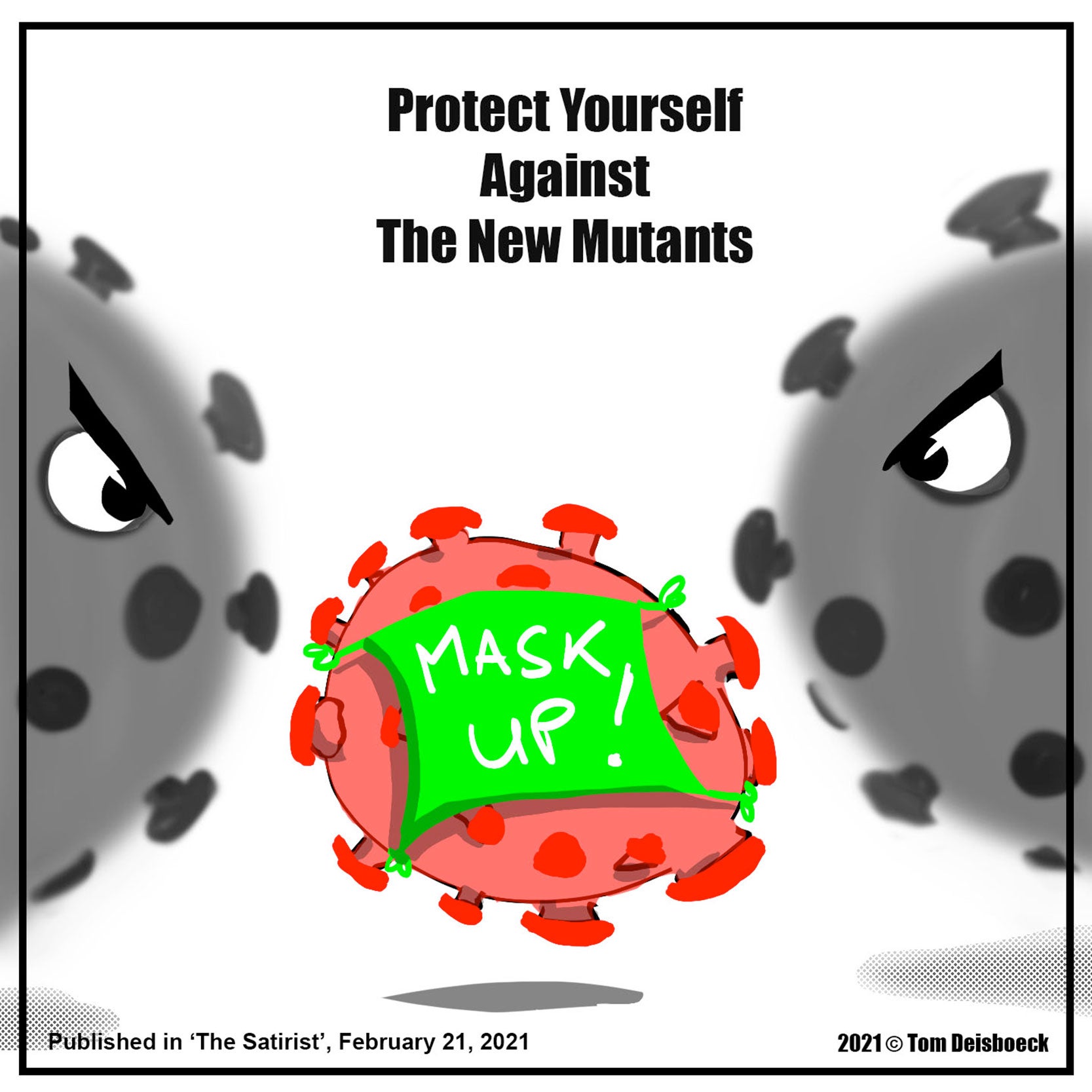

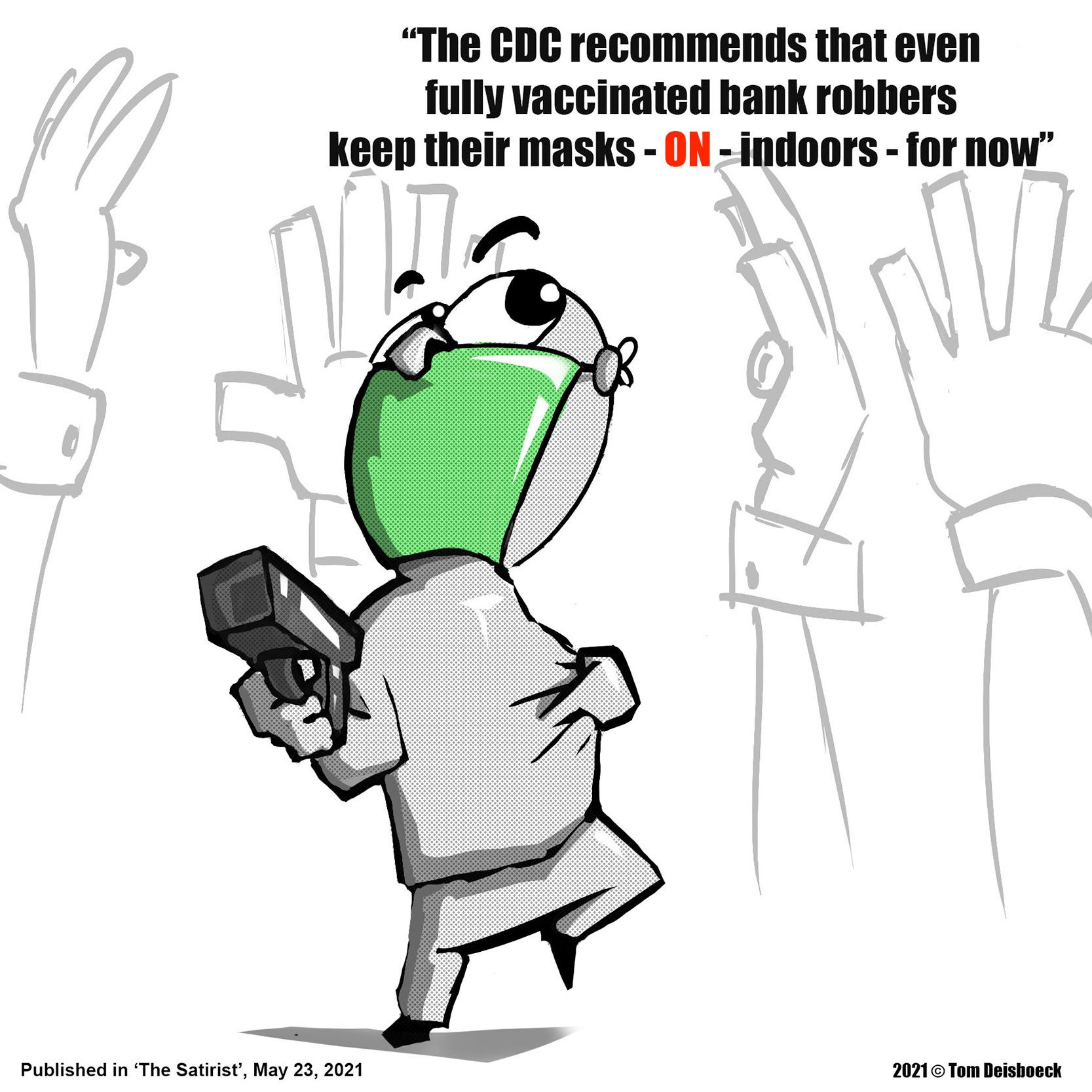

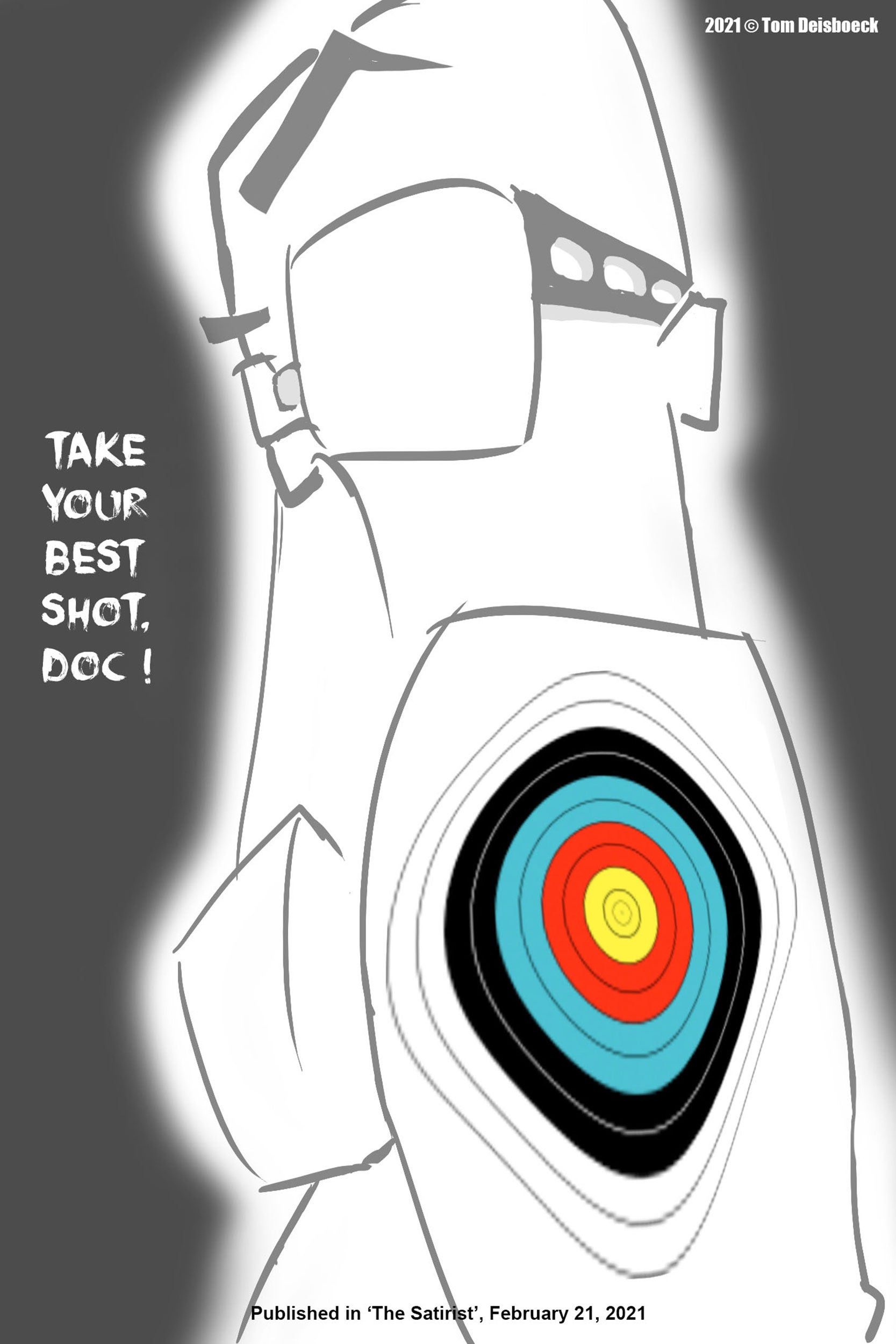

Thomas Deisboeck is exploring whether art and multimedia, including cartoons about COVID-related masking, can improve health communications. These cartoons appeared in The Satirist this year.

Illustrations by Thomas Deisboeck

If Deisboeck had his way, pro-vaccine messages and health communications on an array of topics would be just as powerful as those of anti-vaxxers. Deisboeck is something of a medical entrepreneur. He received his M.D. from the Technical University of Munich in 1996 and today conducts research in complex biosystems, from oncology to COVID-19.

But he also went to business school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduating in 2011, and has consulted on digital health care in the U.S., Europe, and Asia. And then there’s his passion for cartooning. Deisboeck took up the art form in high school, put it down a few years later in favor of his medical studies, but returned to it in recent years. Today, he’s at work illustrating children’s books, an upcoming series, and penning single-panel editorial cartoons that appear in publications like the online parody site The Satirist.

Deisboeck organized the seminar to take advantage of what he perceived as a moment of opportunity to improve health communications. Cartooning and graphic arts, even comic books, have been used in the past, but only rarely in an effective, coordinated way that can make a difference in patients’ behavior, improve adherence to treatment plans, hike their understanding of medical conditions, and improve things like vaccine uptake. Technology, Deisboeck said, offers the chance to try new approaches, like video games and virtual-reality headsets, as is done for kids undergoing chemotherapy at Boston Children’s Hospital.

In some ways, the fight will be not just to innovate, but to convince administrators that the battle is worth the time and resources. Betancourt said that health communications has never received the kind of attention it deserves. He pointed out that there already are principles for effective communications — using graphics, easy-to-understand language, simple messages that capture an issue’s core.

“The science is there on how to do it. But neither the time nor the resources are invested in doing it all the time for everyone,” Betancourt said. “In general, health care has not put a premium on being thoughtful and creative around their communications. They haven’t followed the science as much as we should. The gap is literally investments in time, resources, and creativity.”

For Deisboeck, the existing challenge is to build on the exploratory seminar’s brainstorming, to convince the medical establishment that this is not only important, but has the potential — if done right, by recruiting top-level talent and investing time and resources — to make a significant difference. During the seminar, he said, work focused on strategies to reach four groups: those for whom English is a second language, Latino families, the elderly, and medical students.

“We have tools — digital tools, platforms — that could actually take it to the next level,” Deisboeck said. “Even at these top institutions, it’s still very much on the innovation side. Clearly this is cool, kids take to it, we think there’s a benefit, but how do we institutionalize the effort? How do we actually get it into the mainstream?”

One way, Deisboeck said, would be to mount a pilot study that illustrates outcome improvements with concrete statistics, like treatment adherence and hospital readmission rates. Once those numbers are in hand, discussions can begin about the issue of paying for it — will it be reimbursable? Considered part of treatment?

“Health care and medicine are very data-driven,” Deisboeck said. “No one will dispute that it looks better, but ultimately, visual-art-supported communications will only stay around if it really does improve care, measurably, and if we can afford it.”