“It’s the young adults and the children who are being impacted and the effects are going to be long-lasting,” said Shekhar Saxena, former director of the World Health Organization’s Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

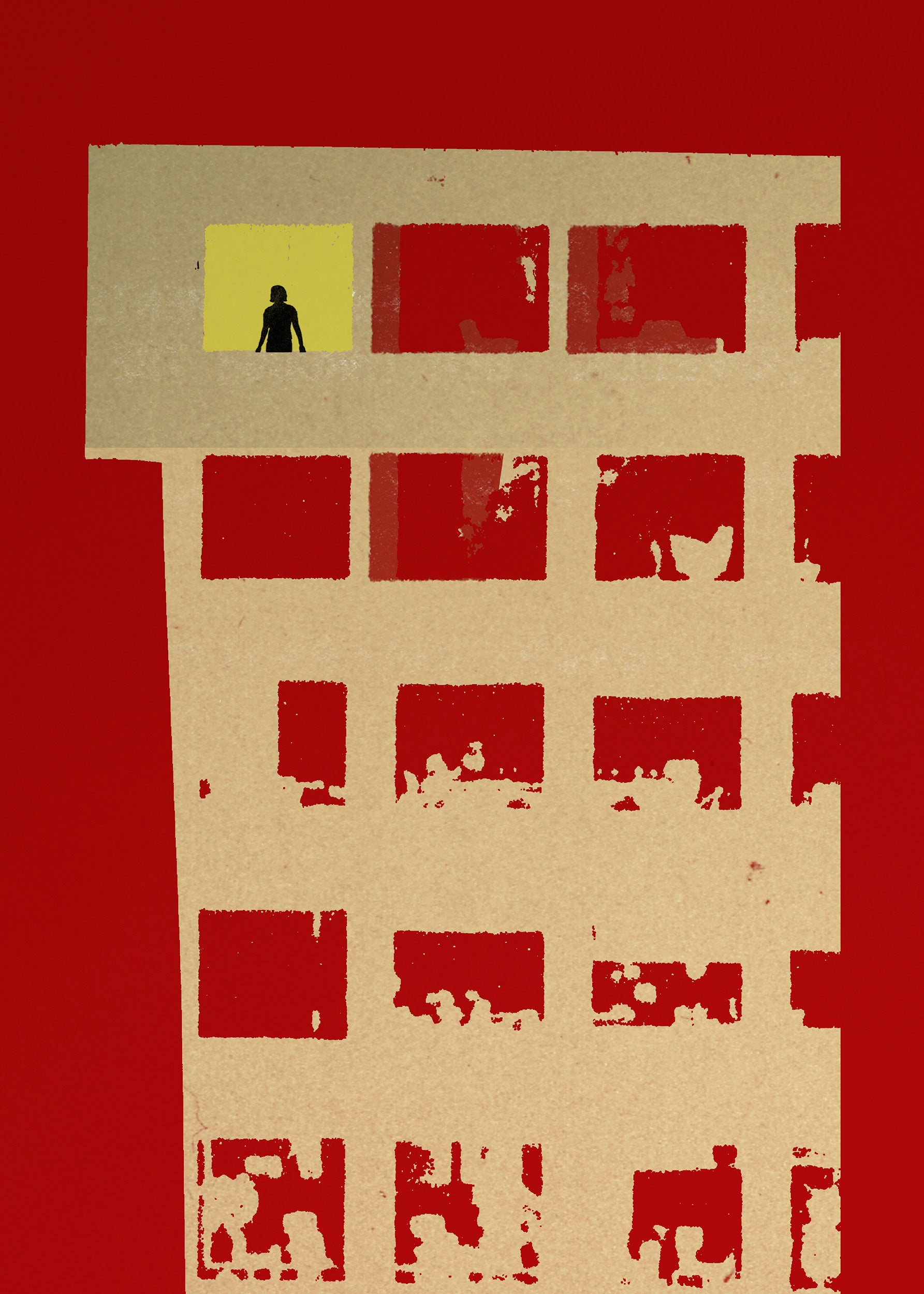

Pandemic pushes mental health to the breaking point

Experts say young, frontline workers could suffer long-term effects

Long after vaccines have tamed COVID-19’s physical impacts, its mental health effects will linger, a panel of experts said Wednesday, citing increased anxiety and depression, accelerated retirements of burnt-out doctors and nurses, and continuing emotional fallout for low-wage workers who toiled despite increased risks at grocery stores, food processing plants, and other essential businesses.

Experts from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), and the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation gathered for an hourlong online discussion of what may be one of the pandemic’s most painful if lesser-recognized effects.

COVID-19’s most severe physical impacts have been felt by the elderly, the experts said, but some of its worst mental health effects have emerged in children — isolated from friends and missing educational opportunities when they should be striking out and finding out about themselves — and young adults, many of whom are struggling with reduced wages and lost jobs layered on child-care and elder-care responsibilities.

“COVID is impacting the older age group more, but anxiety and depression are being faced by the young adults much more, which is exactly the opposite of what we’ve seen in some of the earlier crises,” according to Shekhar Saxena, professor of the practice of global mental health and former director of the World Health Organization’s Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. “It’s the young adults and the children who are being impacted and the effects are going to be long-lasting.”

Ken Duckworth, NAMI’s chief medical officer, said that data showed that about one in five Americans suffered from some sort of mental illness before the pandemic, and that number is now two in five. Virtually every country has reported disruption in mental health services, though in some cases, as in the U.S., telehealth services have expanded to fill some of the void.

“The past year has been terribly damaging to our collective mental health. There is no vaccine for mental illness.”

Michelle Williams, dean of Harvard Chan School

“It’s very clear through a very comprehensive CDC study, that that number is over two in five [Americans], for anxiety, depression, trauma. We’re seeing more kids visit emergency rooms and more kids receiving services,” Duckworth said, adding that, according to calls to the NAMI helpline, there’s also a substantial increase in people seeking help navigating the mental health care system for themselves or a loved one. “Across the board, we’re seeing that the pandemic has had a very substantial mental health impact.”

The event, “Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19,” was presented by the Chan School and NAMI. Chan School Dean Michelle Williams introduced the discussion, saying that even before the pandemic, mental health care was an area of need in the U.S. Now, after months of “the dire strain we are all under,” it has become even more acute, particularly among the young and disadvantaged.

“The past year has been terribly damaging to our collective mental health,” Williams said. “There is no vaccine for mental illness. It will be months, if not years before we are fully able to grasp the scope of the mental health issues born out of this pandemic. Long after we’ve gained control of the virus, the mental health repercussions will likely continue to reverberate.”

The event also included Professor of Psychiatric Epidemiology Karestan Koenen, as well as two NAMI ambassadors. One of the ambassadors, actress DeWanda Wise, spoke of her own struggles with mental health and how counseling still provides important support today. The other ambassador, Cleveland Browns lineman Chris Hubbard, detailed his own mental health struggles from the perspective of a Black man in a field that values toughness. Hubbard said he sought help after anxiety about performing his best on the field spilled into his non-football life.

“A lot of us guys think ‘We’re OK,’ but we’re just as human as anyone else,” Hubbard said.

Corey Feist, co-founder of the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation, established after the suicide of New York emergency room physician Lorna Breen in April, said society needs to support the people who have been, in essence “running into the burning building” every day of the pandemic. Feist, who is Breen’s brother-in-law, said he’s working on congressional legislation to increase funding and promote mental health best practices as a way to help frontline workers who have borne the pandemic’s mental strain.

More like this

That strain, Feist and Duckworth said, is having a damaging impact on the health care field. Duckworth said the equivalent of a “whole medical school class” of physicians is lost to suicide every year, while Feist said surveys of nurses and doctors show that many are considering leaving the field in the next two to five years.

“We already have a nursing shortage and physician shortage in this country, but because of the burnout and mental exhaustion and now, frankly, the trauma they’re experiencing on a daily basis, I think it’s only human that we will see an exodus from the profession, despite their calling to go into it,” Feist said. “This has become an occupational hazard for nurses and physicians, to sacrifice their mental well-being in exchange for taking care of patients.”