Snow White and the darkness within us

Maria Tatar collects versions of the tale from around the world and explains how they give us a way to think about what we prefer not to

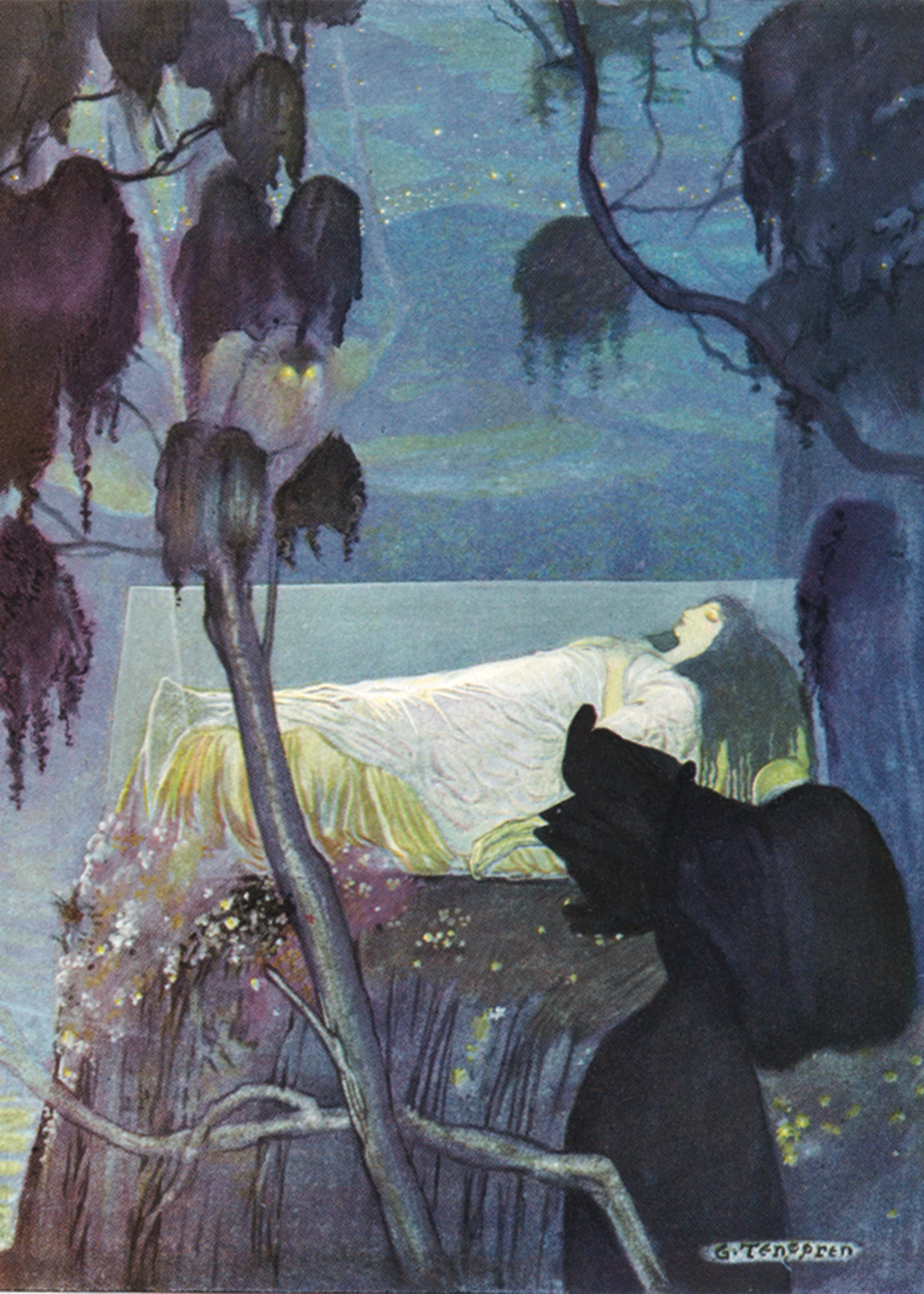

A 1923 illustration of Snow White resting in a glass coffin by Gustaf Tenggren, a Swedish American illustrator who worked as an animator for The Walt Disney Co. in the 1930s.

Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was released as the first feature-length animated film in 1937, and decades later, the musical fantasy based on a Grimm Brothers fairy tale about the complications and conflicts in the mother-daughter relationship is still a cultural touchstone. The story has virtually eclipsed every version of the many told the world over about beautiful girls and their older rivals, often a cruel biological mother or stepmother, but sometimes an aunt or a mother-in-law. In her new book, “The Fairest of Them All: Snow White and 21 Tales of Mothers and Daughters,” Maria Tatar, the John L. Loeb Research Professor of Folklore and Mythology and Germanic Languages and Literatures and a senior fellow in Harvard’s Society of Fellows, collected tales from a variety of nations, including Egypt, Japan, Switzerland, Armenia, and India. She spoke to the Gazette about her lifelong fascination with the saga and how we can look to fairy tales to navigate uncertain times.

Q&A

Maria Tatar

GAZETTE: Why did you decide to take up the Snow White story?

TATAR: While working on my previous book with Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr., “The Annotated African American Folktales,” I came across a South African story called “The Unnatural Mother and the Girl with a Star on Her Forehead.” It was basically what we call the Snow White story, but in it the “beautiful girl” falls into a catatonic trance after putting on slippers given to her by her jealous mother. That’s when I fell down the rabbit hole of wonder tales and discovered stories from all over the world in which a stunningly attractive young woman arouses the jealousy of a woman who is usually her biological mother. The Brothers Grimm, whose 1812 story inspired Walt Disney to create the animated film, had many vernacular tales available to them, but they chose to publish the one in which the rival is the stepmother, in part because they did not want to violate the sanctity of motherhood. Now, decades later, it is still our cultural story about the many complications and conflicts in the mother-daughter relationship. It has eradicated almost every trace of the many tales told all over the world about beautiful girls and their rivals.

GAZETTE: Why does this particular story remain so resonant?

TATAR: All of the tales in this collection are cliffhangers. They begin with the counterfactual “What if?” then leave us asking “What’s next?” and finally challenge us to ask “Why?” These stories were originally told in communal settings, and they got people talking about all the conflicts, pressures, and injustices in real life. How do you create an ending that is not just happily ever after, but also “the fairest of them all”? What do you do when faced with worst-case possible scenarios? What do you need to survive cruelty, abandonment, and assault? In fairy tales, the answer often comes in the form of wits, intelligence, and resourcefulness on the one hand, and courage on the other. With their melodramatic mysteries, they arouse our curiosity and make us care about the characters. They tell us something about the value of seeking knowledge and feeling compassion under the worst of circumstances, and that’s a lesson that makes us pay attention today.

“All of the tales in this collection are cliffhangers. They begin with the counterfactual ‘What if?’ then leave us asking ‘What’s next?’ and finally challenge us to ask ‘Why?’”

GAZETTE: Can you explain the connection between Snow White’s skin color and her innocence and goodness?

TATAR: The red, white, and black color coding in many European versions of this story reminds me of how the Grimms believed that those were the colors of poetry. Their beautiful girl is “white as snow, red as blood, and black as the wood on this window frame.” It was Disney who changed that to “lips red as the rose, hair black as ebony, and skin white as snow.” When you look at other versions of the story, you realize that, generally, the daughter’s skin color is not an issue, though, curiously, there is a Samoan version of the tale with a girl with albinism who is an outcast. The fact that the beautiful girl in a global repertoire of stories about mothers and daughters is stereotyped as having skin white as snow because of the influence of the Grimm and Disney versions limits the global cultural resonance of the story. There’s nothing sacred about the Grimms’ version of that fairy tale or about Disney’s reimagining of it, but we tend to think of Grimm and Disney as the “originals,” and, unfortunately, they have become the “authoritative” versions.

GAZETTE: What are some of the themes or morals that you found across the tales you collected for this volume?

TATAR: Tales about beautiful girls circulated in adult storytelling cultures, in communal settings. They gave parents a way to talk about, think about, and address their own complicated feelings and unacknowledged resentment about raising children only to have them grow up and exceed you in one way or another. Myths and fairy tales enact all the fantasies, fears, anxieties, and terrors stored up in our imaginations that we are ordinarily afraid to talk about. By amplifying and exaggerating real-life conflicts, folktales animated our ancestors, getting them to sit up, listen, and think. In the safe space of “once upon a time,” they could explore taboo subjects and talk about the dark side of human nature. They are the symbolic stories that help us talk about and navigate the real. That’s why a psychologist like Bruno Bettelheim saw in the telling of the stories a form of therapeutic value.

But there is more to these stories than cathartic release. Fairy tales are also a great contact zone for all generations, enabling us to think more and think harder about crisis, resources, and recovery in a whole range of situations: famine, expulsion, abduction, loss, dispossession, enslavement, and so on, all the terrible things that can happen to us.

GAZETTE: Were there any versions of the story that surprised you in their approach?

TATAR: I think that almost every version of Snow White surprised me in one way or another. There’s a Swiss story called “The Death of the Seven Dwarves” in which you have all the tropes of the Snow White story, but scrambled up. A homeless child finds protection with seven dwarves, and an old woman comes knocking on the door, seeking a bed for herself as well. When the girl refuses to offer shelter, the old woman denounces her as a slut and accuses her of sleeping with all seven of the dwarves. This is pretty heady stuff, and that tale made it clear to me that these stories were never really for children. They were meant to entertain adults while they were spinning, sewing, repairing tools, and doing chores late at night. John Updike tells us that fairy tales were the television and pornography of an earlier age, and a story like that is revelatory about the true uses of enchantment.

GAZETTE: You say that fairy tales are larger than life and can reflect and magnify our fears and anxieties. What do you think fairy tales can provide during this time of uncertainty and fear during the COVID-19 pandemic?

TATAR: One of my favorite fairy tales, “Hansel and Gretel,” starts in a time of famine. How do you manage to stay alive when your parents throw you out? The philosopher Walter Benjamin put it beautifully when he said that fairy tales transmit one big lesson: You need wits and courage to confront the monsters out in the woods.

There’s no practical advice or wisdom to be drawn from the lore of times past. But our ancestors did use these stories to talk with each other about the tools you need to survive, and what is often modeled in fairy tales is an instinct for compassion and collaboration. I think here of all those grateful animals that are not slaughtered and then turn up to help carry out an otherwise impossible task. In the time of a pandemic, something global that affects all of us, the golden network of storytelling reminds us of everything we share, that we are all human, and that solidarity and caring for each other build a path forward to developing the tools and knowledge we need for healing.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.