Panelists Alexis Stokes, (clockwise from upper left), Ande Durojaiye, Evelynn Hammonds, Tiffany Pogue, and Tracy Robinson-Wood speak during the SEAS & FAS Division of Science Community Conversation for a virtual panel and Q&A. They discussed racial injustice, dealing with racial trauma, and strategies for change.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Racism, coronavirus, and African Americans

Panel discusses long-festering wounds of racial inequities and possible steps forward

Heavy. Overwhelming. Daunting. Those were some of the words used at a recent panel to describe the two crises disproportionately affecting the black community right now: the novel coronavirus and the unjust killing of African Americans by white police officers.

“It’s just heavy,” Ande Durojaiye, Northern Kentucky University’s vice provost for undergraduate academic affairs, said. “It’s a lot of things that are happening at one time and a lot of things that are weighing pretty heavily. Prior to the incidents surrounding George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, we were dealing with the global pandemic of COVID-19. As African Americans, we were disproportionately being impacted, and it continues. So, when you’re dealing with that and working through that, to then have it coupled with this huge national outrage around an issue that has, frankly, been going on since the beginning of the country, it’s a lot, and it’s a lot to balance. … You feel like it’s compounded to the point where you wonder: How do we get out from under?”

Durojaiye was part of a four-person virtual panel discussing racial injustice organized by the diversity, inclusion, and belonging officers in the FAS’ Division of Science and the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Other participants in last Tuesday’s session were Evelynn Hammonds, Harvard’s Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz Professor of the History of Science and a professor of African and African American studies; Tiffany Pogue, an assistant professor of education at Albany State University; and Tracy Robinson-Wood, professor of applied psychology at Northeastern University’s Bouvé College of Health Sciences. More than 600 attendees were led in a moment of silence by Dean of Science Chris Stubbs and SEAS Dean Francis J. Doyle III, before Alexis J. Stokes, director of diversity, inclusion, and belonging, began moderating the conversation.

“You feel like it’s compounded to the point where you wonder: How do we get out from under?”

Ande Durojaiye

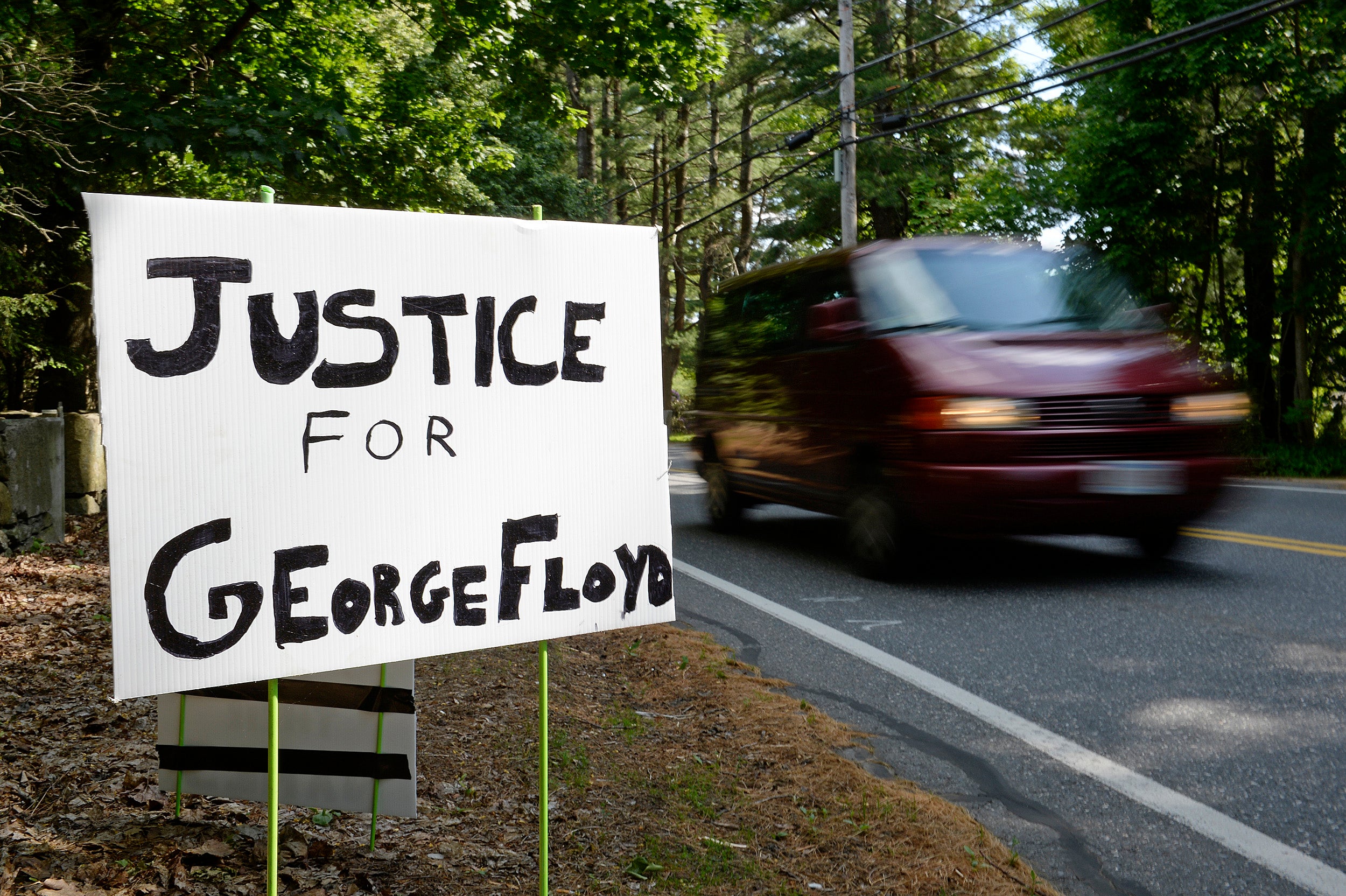

The conversation revolved around examinations of why black Americans have higher rates of infection and death from the novel coronavirus and the proliferation of rage and protest across the nation in response to the death of George Floyd after a white Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes during an arrest. Panelists discussed ways to deal with trauma caused by structural racism and strategies to overcome some of these longstanding issues, including a focus on addressing racial bias and being an effective ally.

“For me, starting with seeing the outbreak of COVID in China, as a historian of science and medicine, I knew it was only a matter of time before it arrived to the United States and therefore following that it was only going to be a matter of time when the virus struck at the most vulnerable people in our population,” Hammonds said. “For African Americans, in particular, historically, we have been disenfranchised with respect to access to health care, to vulnerabilities based on the social determinants of health, housing, work, all the kinds of things that would make our people more vulnerable to the virus than many others. … Then following that, we have the incident that happened in Minneapolis [that] just ripped the scab off what was already a festering wound of racism in this country.”

More like this

“There’s something about racism that works in this country because the same brokenness that Emmett Till’s mother had in 1955 when her child was murdered, that’s what George Floyd’s family is dealing with right now. This is 60 years later,” Robinson-Wood said. “Unfortunately, there will be more situations like this that we are grieving now.”

A main focus of the conversation involved the generation of ideas on ways colleges and universities can promote diversity through student recruitment and the sustained hiring of faculty and staff to adequately mentor and support each group.

Panelists said it’s not enough for institutions to simply state they’re committed to diversity or hire diversity officers or focus on racial issues when responding to periods of unrest or a crisis, but to consistently work on and communicate how they’re addressing inequities.

“That’s definitely the key, that internal, constant, consistent reflection on why we make the decisions we make is imperative for anyone who is interested in addressing issues of race,” said Pogue.

“We just represent the beginning of the conversation,” added Hammond. “In so many places, it seems to me, once you’ve appointed a diversity officer, people think that’s the end of the story. ‘We have the person who’s supposed to take care of that, and now we can just keep doing what we want to do, because we really do have it covered.’ You do not have it covered, and what happens is, it seems to me, that actually in certain respects it’s just a placeholder, just like the language of diversity and inclusion in mission statements. The intent was never to put forward an action plan that was going to get us from A to B.”

Pogue also said it’s important to understand racial biases and assumptions when considering issues playing out in the media, like the fallout from the confrontation between Amy Cooper, the white woman who called the police on Christian Cooper, a Harvard-educated African American man who was bird-watching in Central Park.

“Why does his educational background come up in the conversation? It doesn’t make sense. Why does it matter whether or not a man had a criminal record? It shouldn’t. Why does it matter? That Breonna Taylor may have once dated someone who practiced illegal activities, allegedly. None of that should matter,” Pogue said. “When we engage in the conversations around someone’s work as a victim to brutality [or injustice], then we are subconsciously saying that only some of us deserve protection and the others of us may be expendable. So even in the bias awareness, we have to constantly be checking our own language, and how we make arguments about these things.”

Panelists also spoke about the importance of allies, a popular topic during the Q&A portion.

At one point, Durojaiye flipped the question, putting the onus on potential allies to engage in self-reflection and commit to tangible actions.

“You all are extremely intelligent people. You all have done quite a bit of work and are experts in various fields; you can think of things that you can actually do or things that you may have contributed that have negatively impacted the outcome for a certain population,” Durojaiye said. “It goes back to us saying … ‘What are these concrete acts that we can take and think that we can do to ensure that we don’t further perpetuate these stereotypes, these racial barriers that currently exist?’ So if I’m talking to an ally, that’s the first thing I would say: I want you to go back and have that self-reflection because coming to a session and saying, ‘I want to stand with you,’ but I don’t see you really putting your money where your mouth is, so to speak, it doesn’t do anything for me. And then it just is no different than someone who’s sitting on the sidelines.”