Shining a light on a genius

Recognizing prominent architect Julian Abele and his role in designing Harvard’s Widener Library

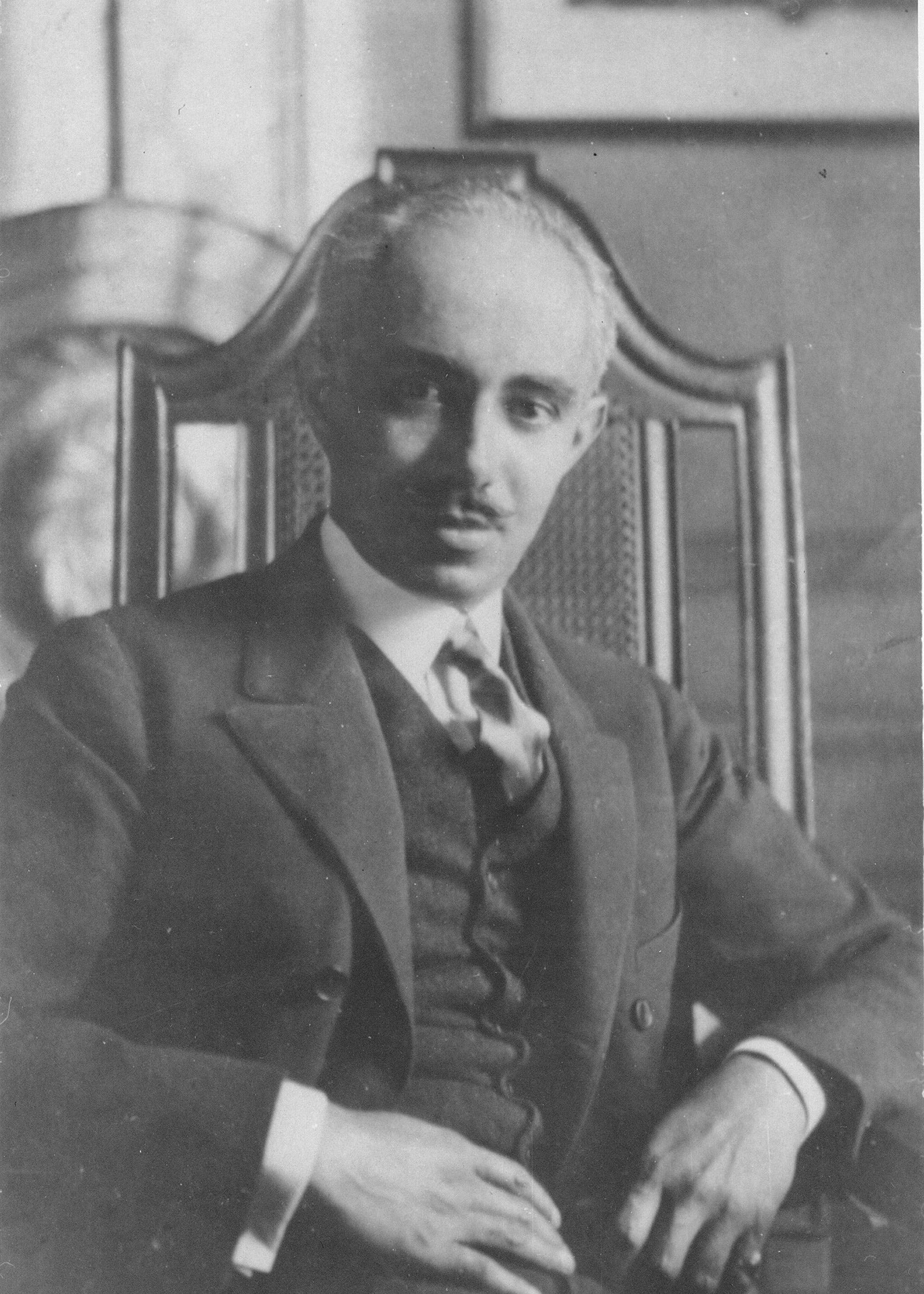

Courtesy of Duke University Archives

In a small glass case beneath the grand dome of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library a collection of ephemera honors Philadelphia-born architect Julian Abele and the major role he played in crafting the signature structure on the Harvard campus, a contribution that until recently had largely gone unacknowledged.

Included amid the photos and correspondence are rich drawings sketched in Europe that shine a light on the talent and artistry of Abele, chief designer for the Philadelphia firm of Horace Trumbauer and the first African American student admitted to the Department of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. Abele, a gifted architect and artist, went to work for the firm immediately after graduating in 1902 and took over the business when Trumbauer died in 1938. Besides Widener, Abele is credited with designing or contributing to the design of more than 200 buildings, among them the Free Library of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as well as much of Duke University’s campus, including its iconic Collegiate Gothic chapel.

“We’re so lucky that this beautiful space where we think and work was designed by one of the most accomplished architects of his time,” said Vice President for the Harvard Library and University Librarian Martha Whitehead. “The fact that he was a black man facing discrimination in a virtually all-white profession makes his achievements even more impressive.”

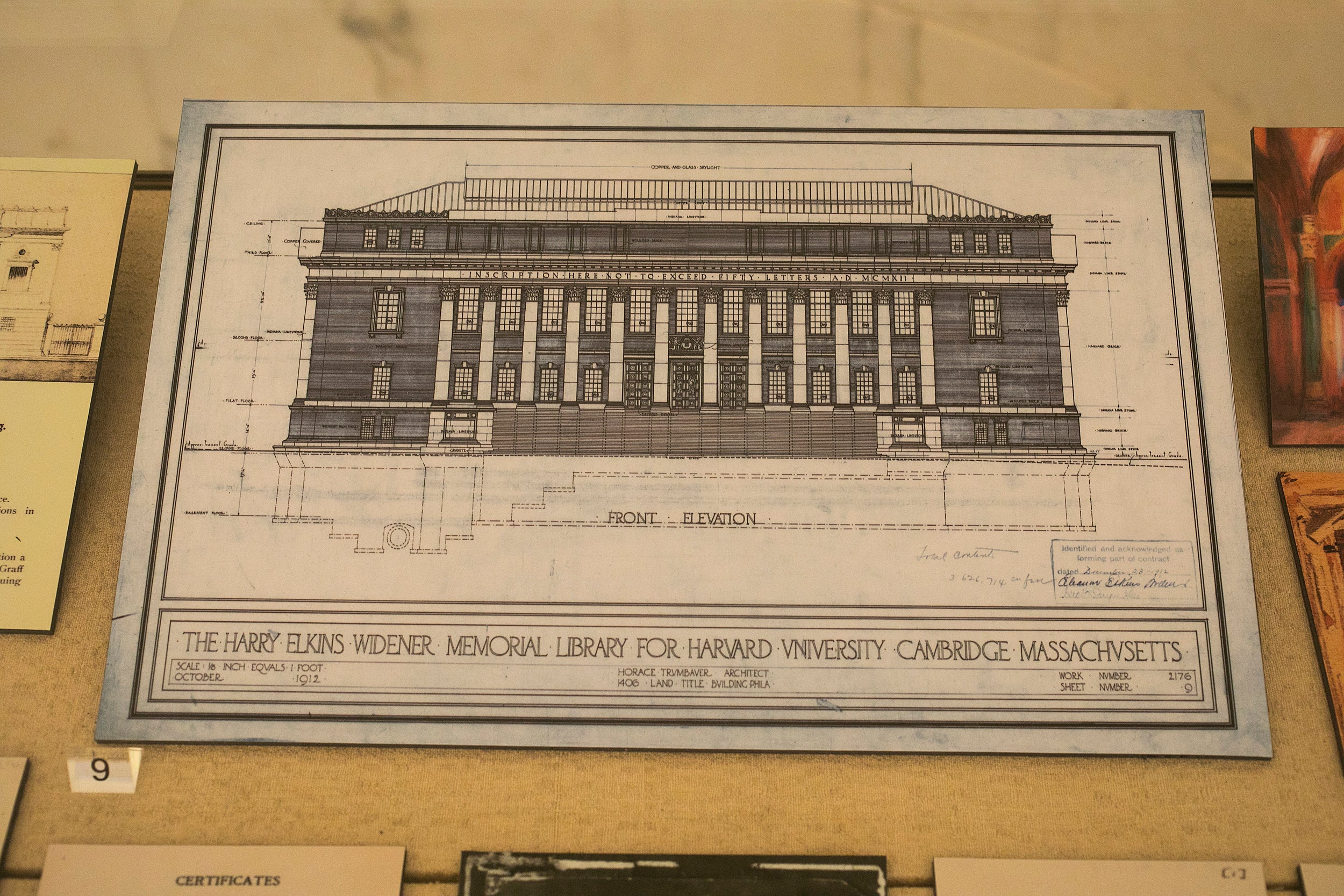

A sketch of the library is featured in an exhibition case within the Widener rotunda.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Though credit for Widener’s look had long been attributed to Trumbauer, Abele is now considered instrumental in the design of the library erected in honor of 1907 Harvard graduate Harry Elkins Widener, who died in the early hours of April 15, 1912. The 27-year-old Widener and his parents were returning from Europe aboard the Titanic when it struck an iceberg and sank off the coast of Newfoundland. Widener’s mother, Eleanor, paid for the library and enlisted Trumbauer’s firm to come up with a plan for its design.

“We know that Abele’s role as chief designer for the firm meant he had an important role in helping design the building,” said Kate Donovan, associate librarian for public services, who curated the display. Clues in the Harvard University Archives point to Abele’s deep involvement in the project. The glass case contains a copy of a letter from July 17, 1912, written by Trumbauer to Archibald Cary Coolidge, then director of the Harvard University Library, introducing Abele and another colleague from the firm and asking Coolidge to “take up with them the detailed requirements for the new Library Building.” In a subsequent letter dated July 23, Coolidge writes to Trumbauer, “It seems to me that there is no need at all of your coming up here this week. We are all agreed on the plan that your men have worked out as a desirable one.”

For years, Abele’s contributions had been hard to pinpoint. Racism played a large part in his lack of recognition, as did the fact that he rarely signed any of his early designs, said Donovan. But experts agree Abele’s imprint on Widener is unmistakable. A skilled artist as well as an architect, Abele studied and trained in the Beaux Arts style in Europe, where he honed his eye, his hand, and his devotion to detail. To see his influence at Widener, said Donovan, all one has to do is look up at the dome’s finely sculpted interior and various flourishes, including the intimate zodiac signs circling the ceiling in the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Room and the carved stone tablet above the library’s main door, featuring the marks of the 15th-century printers Caxton, Rembolt, Aldus, and Fust and Schöffer.

Zodiac signs and other intricate details decorate the library’s interior.

“I think you can really see his artistry,” said Donovan. “I see his name in a lot of those fine details.”

Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor and director of Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, agrees that Abele’s contributions had been too long overlooked.

“Julian Abele represents the history of African American achievement in architecture that has too often been buried but that is now, finally, coming into the light,” Gates said. “It is only appropriate that his genius in designing Widener Library, this unmatched home for generations of scholars — of veritas — is getting its truthful and overdue recognition.”

That recognition is laid out in the display, established in 2018, in which the achievements of the man who once remarked “I lived in the shadows,” are now in plain view.

Donovan said she considers Widener the heart of the University and sees Abele as the person “responsible for that.”

“Recognizing Julian Abele and his role in our history is extremely important,” said Whitehead. “It is our responsibility to honor him, and it was with that in mind that we mounted an exhibit in the library he designed.”