A case study in portraiture

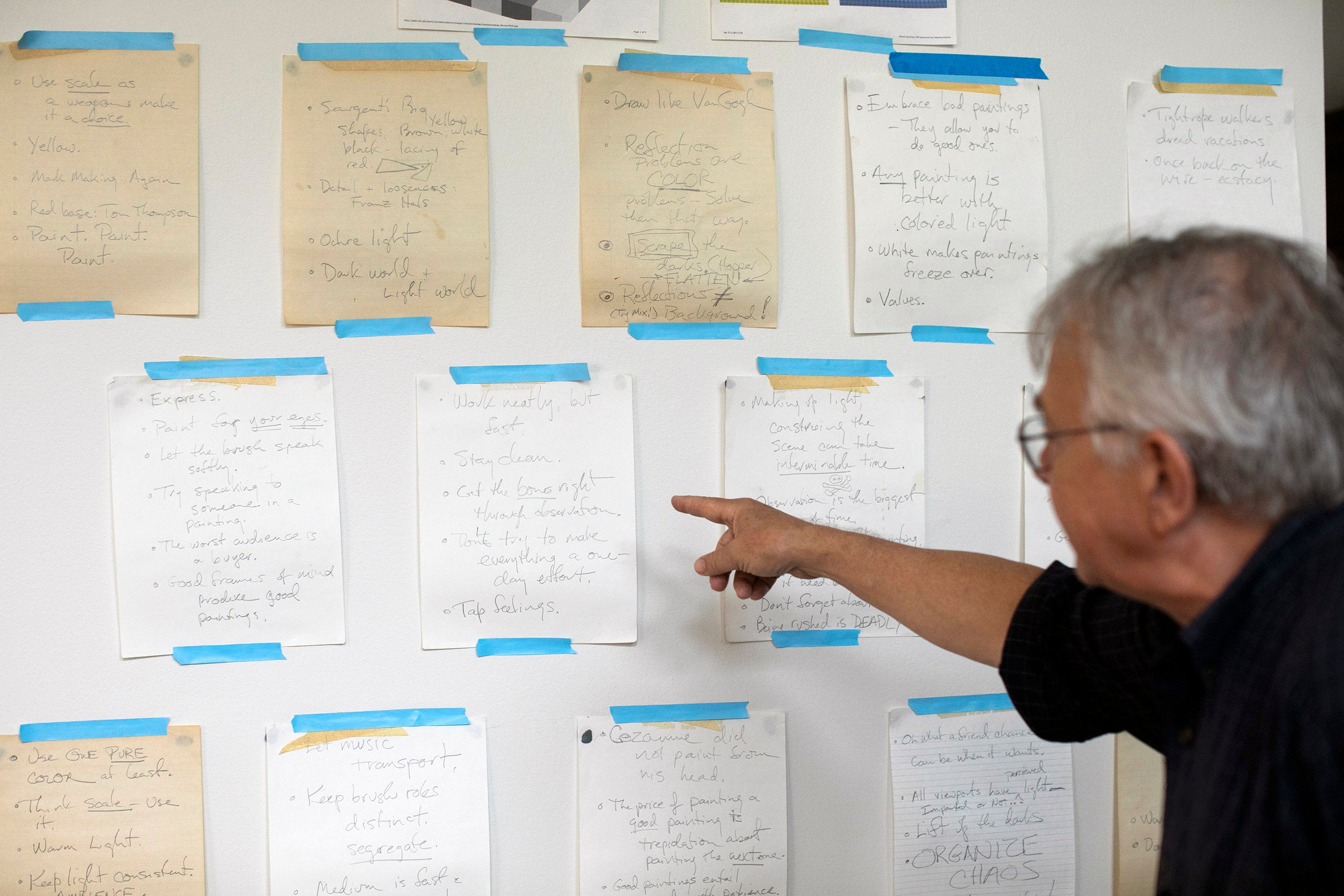

Stephen Coit ’71, M.B.A. ’77, the artist of the Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project, in his Cambridge home.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Stephen Coit’s paintings add diversity, context to Harvard’s walls

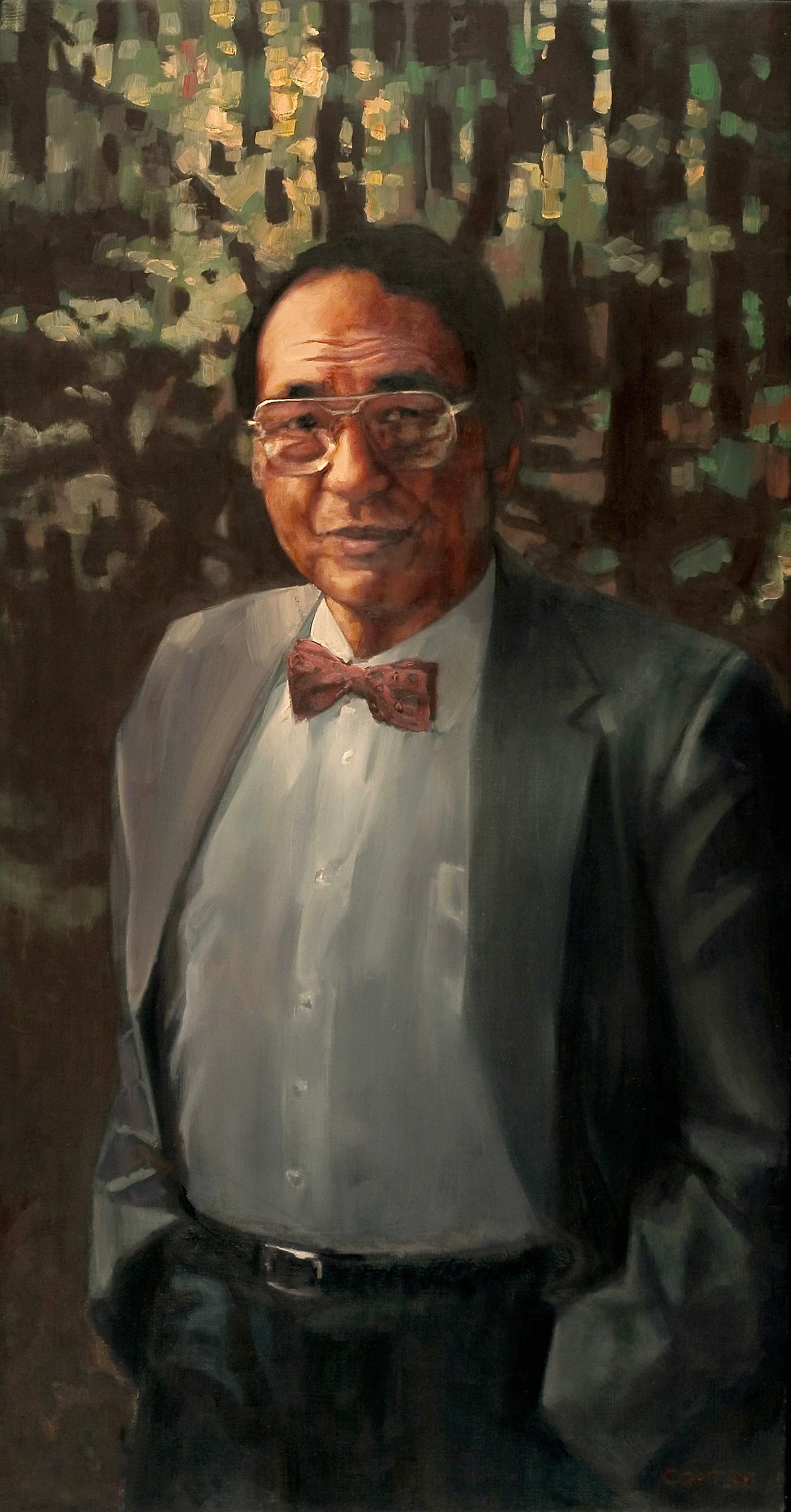

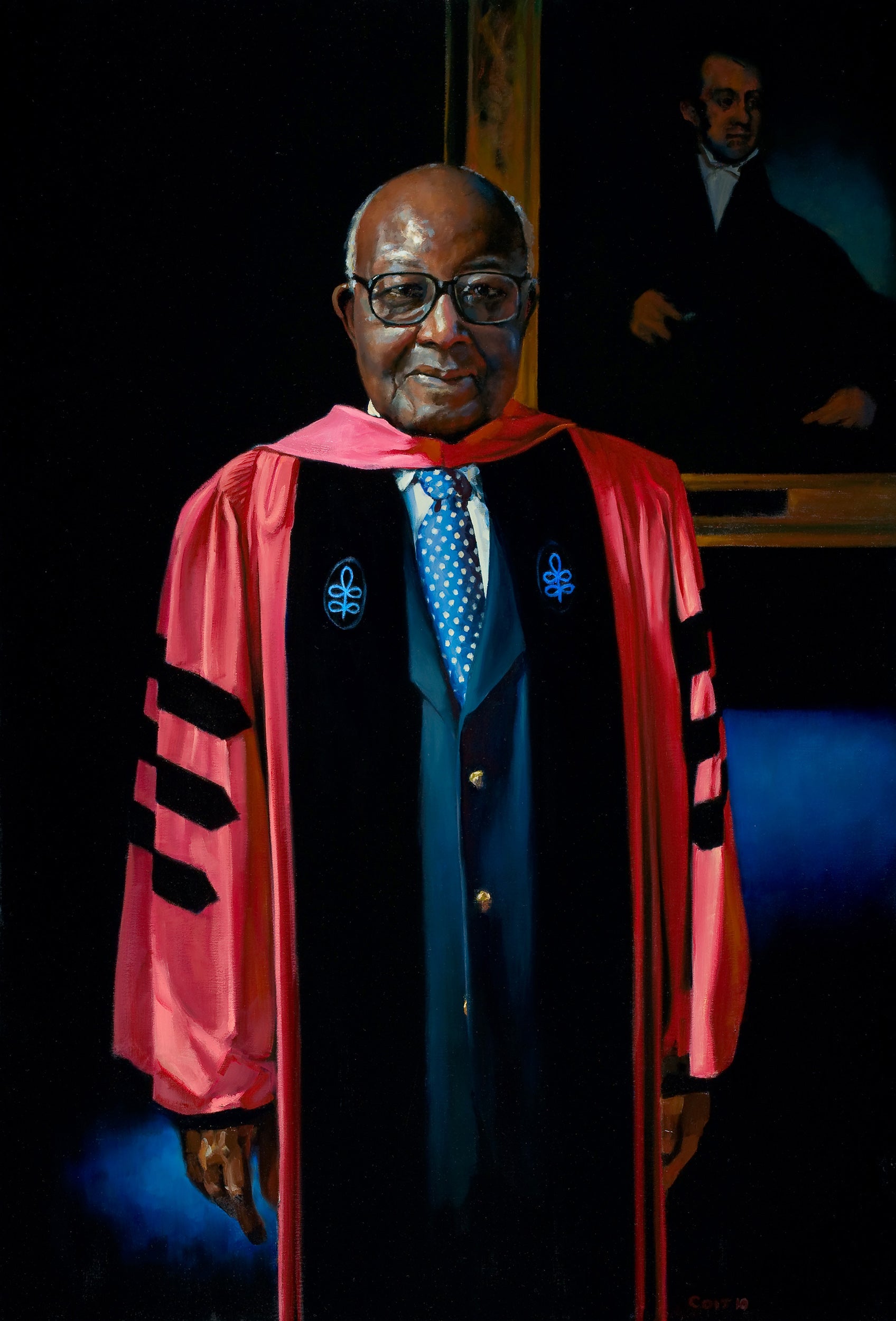

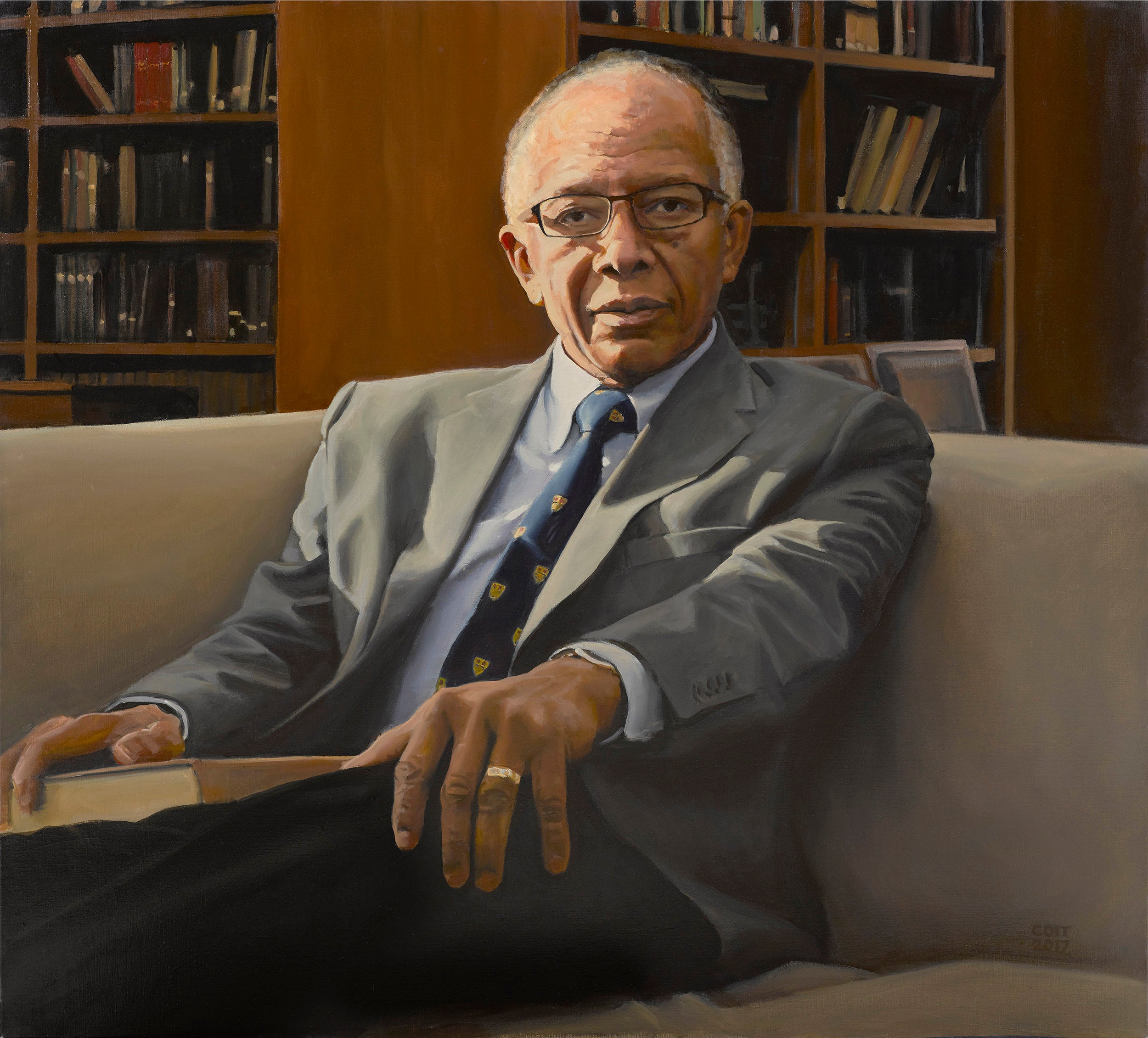

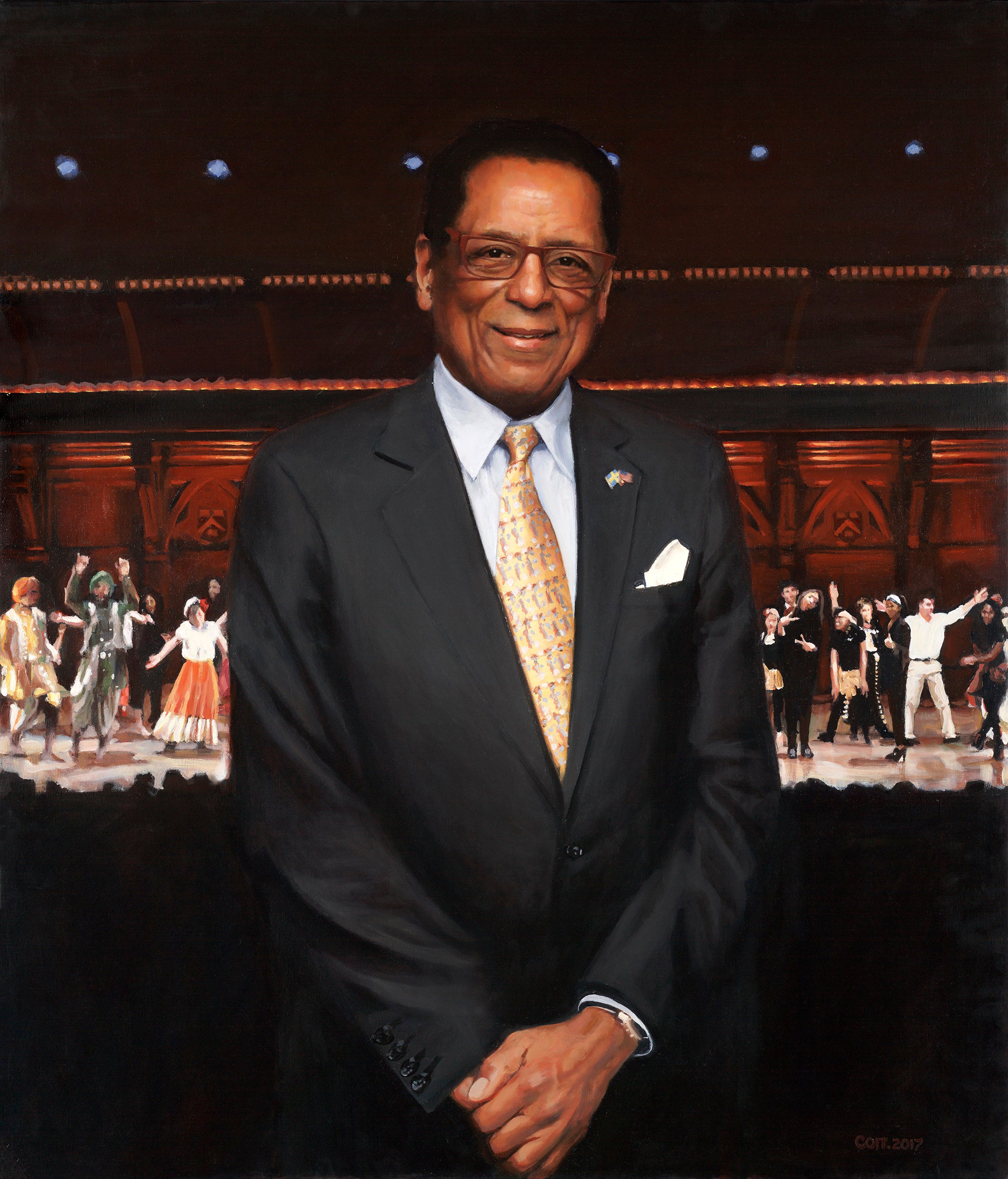

For 15 years, painter Stephen Coit (’71, M.B.A. ’77) has been quietly helping to change the walls of campus by adding dozens of portraits that better reflect Harvard’s diversity.

In a recent interview, he struggled to recall the portraits that had adorned Lowell House when he was an undergraduate except to say, “They were more decorative than inspiring.”

“Male, pale, and Episcopal(e),” said David L. Evans, senior admissions officer, reinforcing the point with a wry smile.

When Coit applied to be the artist for the Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project — launched in 2002 by the late S. Allen Counter, founder of the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations — Evans served on the selection committee. He said he was struck by Coit’s insistence on painstakingly researching his subjects.

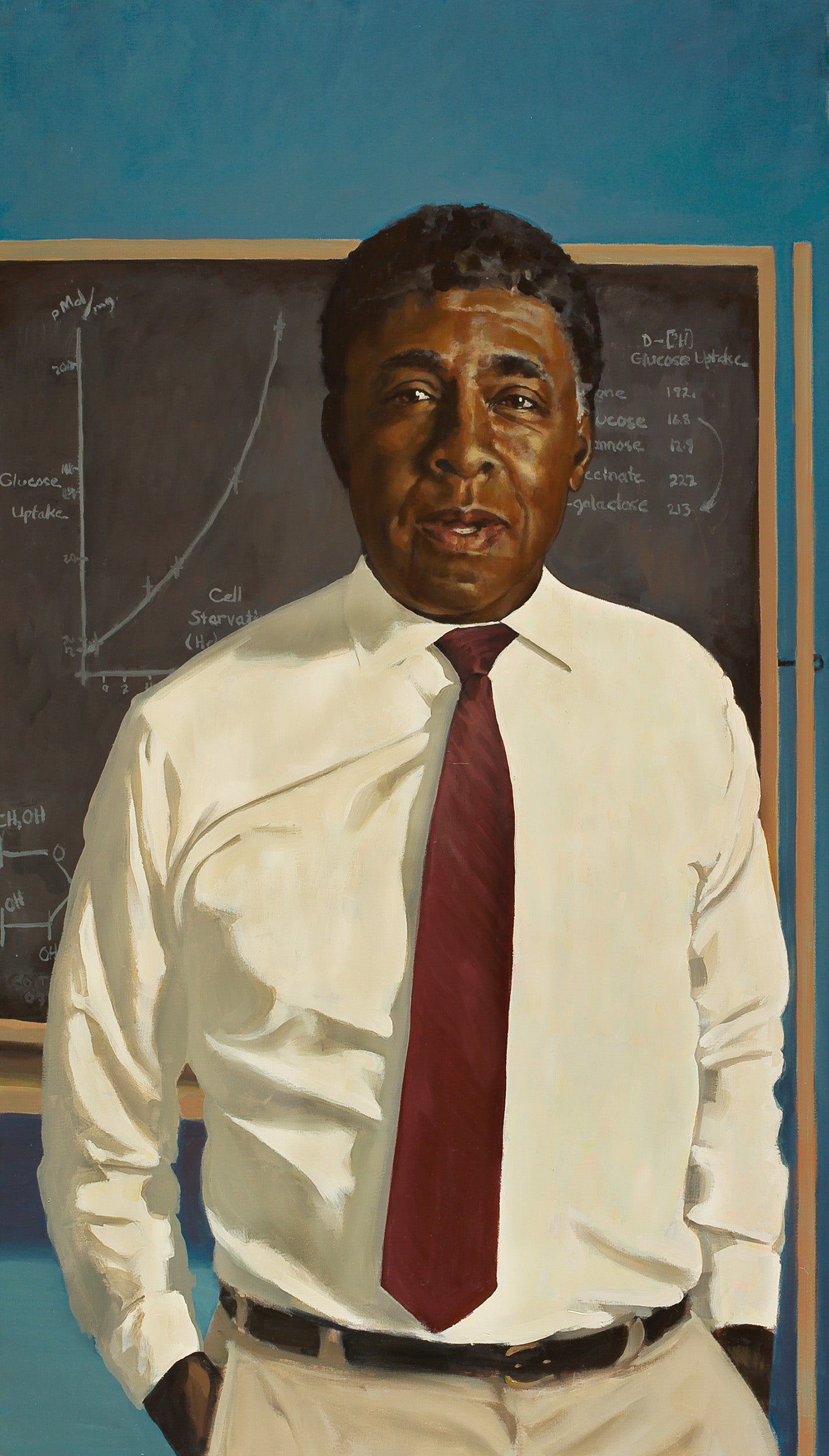

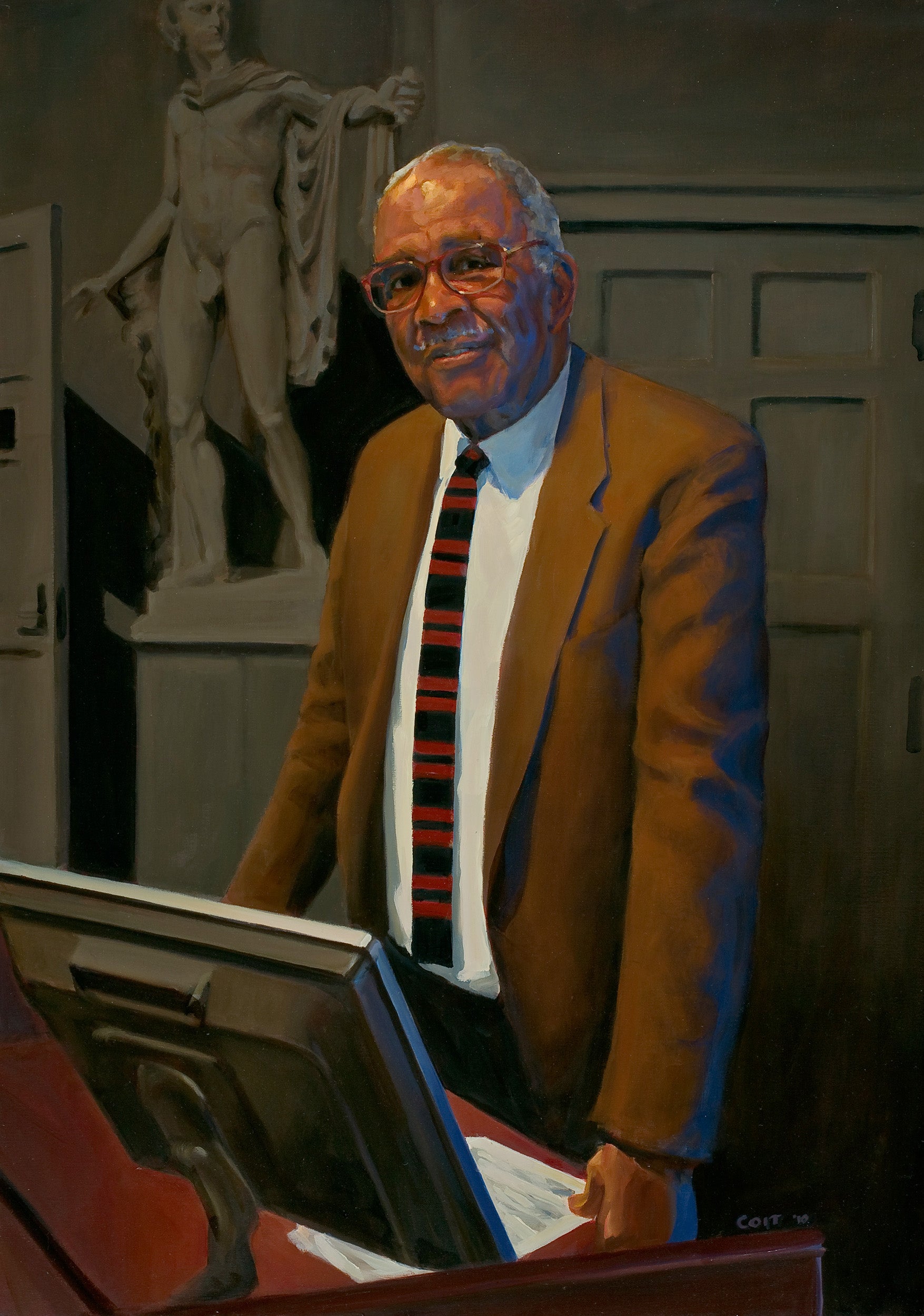

“He wanted to capture, the best an artist can … that spirit behind the physiognomy,” said Evans, who in 2005 himself became the subject of one of Coit’s paintings. (Evans’ portrait is located in the Lamont Library entryway.)

Essential oil colors and brushes lie at the ready.

Counter started the portraiture project with the goal of capturing the diversity of those who have served the University for at least 25 years with distinction.

“Allen Counter was the first one at Harvard, in the modern period, to see the potential culture-changing power of portraits on the walls of the University,” Coit said. “Before that, new portraits at Harvard had been limited mainly to outgoing presidential portraits that were hung in the rarely visited, highly exclusive Faculty Room in University Hall.”

Counter recognized that contemporary portraits of distinguished individuals “who were part of the underrepresented minorities could tell a compelling story that would be immediately apparent to all,” Coit said.

“Unlike Harvard presidential portraits, Foundation portraits would be placed in Houses, libraries, and in spaces like Annenberg, where students would view them on a daily basis, a powerful way to communicate inclusiveness at Harvard.”

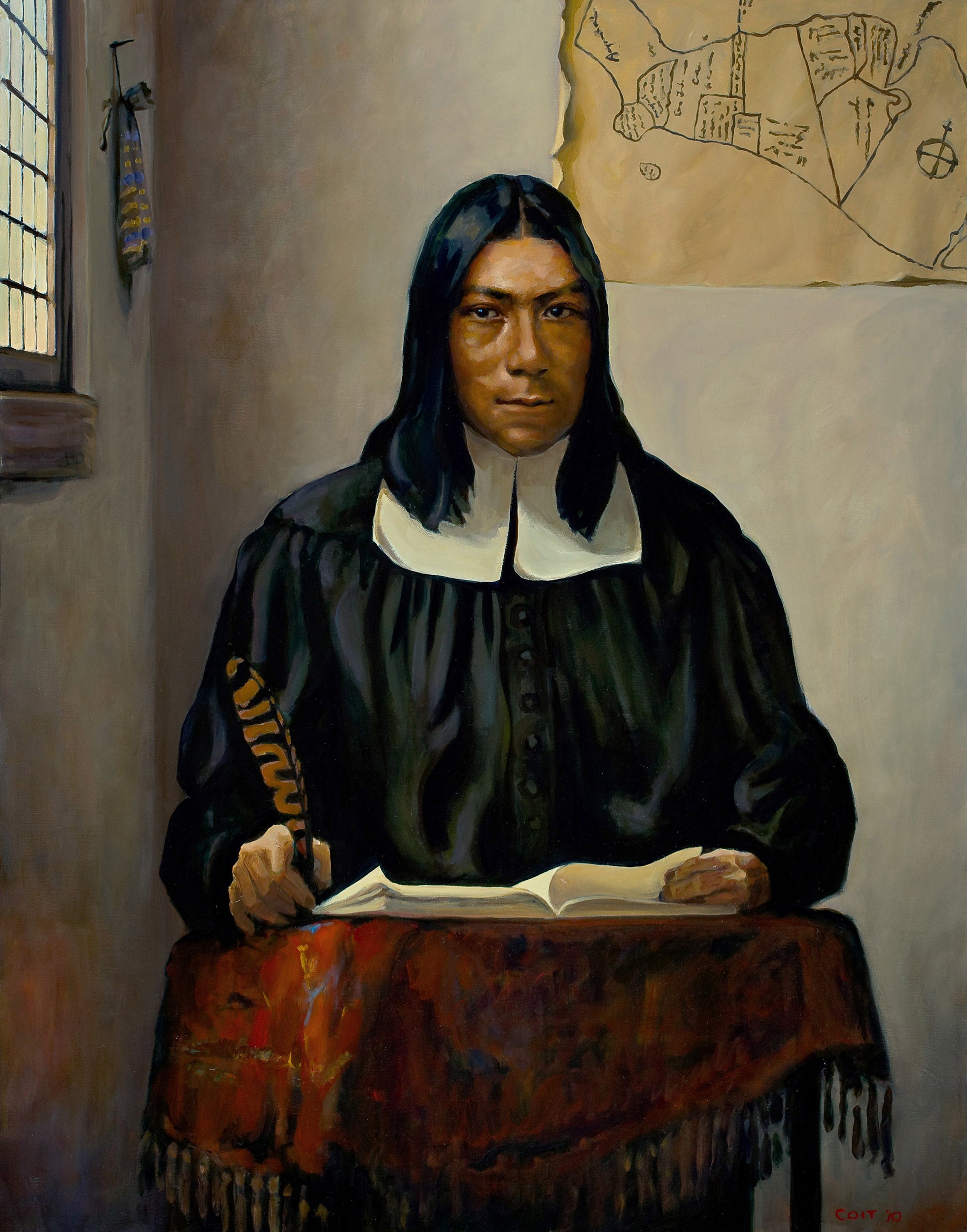

Through the project and other commissions inspired by the Harvard Foundation’s work, Coit has added 26 new faces to the pantheon, among them Robert Tanner Freeman, the first African American to graduate from the Dental School of Medicine and earn a dental degree in the U.S., in 1869, and Richard Theodore Greener, the first African American to graduate from the College a year later in 1870 (his portrait hangs in Annenberg Hall).

Image gallery

“I would always ask my subject, what do you want to say in your portrait? What is the message for future generations? … In a way, each of the portrait artists in my class are writing a case about the subject.”

Coit cut an unusual path to the visual arts from the Business School but said he uses his M.B.A. “every day in painting,” applying lessons learned working for firms such as G.D. Searle and Hewlett-Packard Corp. to his artistic practice.

“I tell many people that want to go into the arts that business school is fabulous training. … It gives you so much flexibility, so much conceptual strength, so much interpersonal strength,” Coit said. “And every good artist is an entrepreneur.”

In recent years, Coit has taught a portrait workshop during Wintersession. “I learned a lot about teaching from going to Harvard Business School. … I guess I teach portraiture by the case method.

“I would always ask my subject, what do you want to say in your portrait? What is the message for future generations? … In a way, each of the portrait artists in my class are writing a case about the subject.”

Anthony Munson ’19 (left), a physics and math concentrator, draws Claude Shannon, the founder of information theory. “Much of portraiture is about forgetting when your mind sees and observing, more carefully than usual, what your eye sees,” Munson said. Becky Jarvis ’19 (drawing a picture of her mother), a linguistics and math concentrator, said, “I definitely wasn’t particularly confident in my artistic ability going into the class. The fact that I could end up with a portrait that I am really proud of — and, for that matter, that everyone in the class could do so — was really great to see.”

“There is something foundational going on here…There is something that says, ‘I am here.’”

– Coit shares during the portrait unveiling of Robert Tanner Freeman.

After more than 15 years, there is a closeness that Coit has achieved with his subjects.

When Freeman’s portrait was unveiled at the School of Dental Medicine, Coit reflected that his subject — the son of enslaved parents — had graduated in the School’s first class of six students only four years after the Civil War ended. It’s conceivable, Coit imagined, that Greener was in the audience as Freeman received his degree, just a year before he made history himself.

Coit closed the unveiling ceremony with, “I would like to give my congratulations to Dr. Freeman. He was a great subject.

“And it was really great getting to know him.”

Share this article