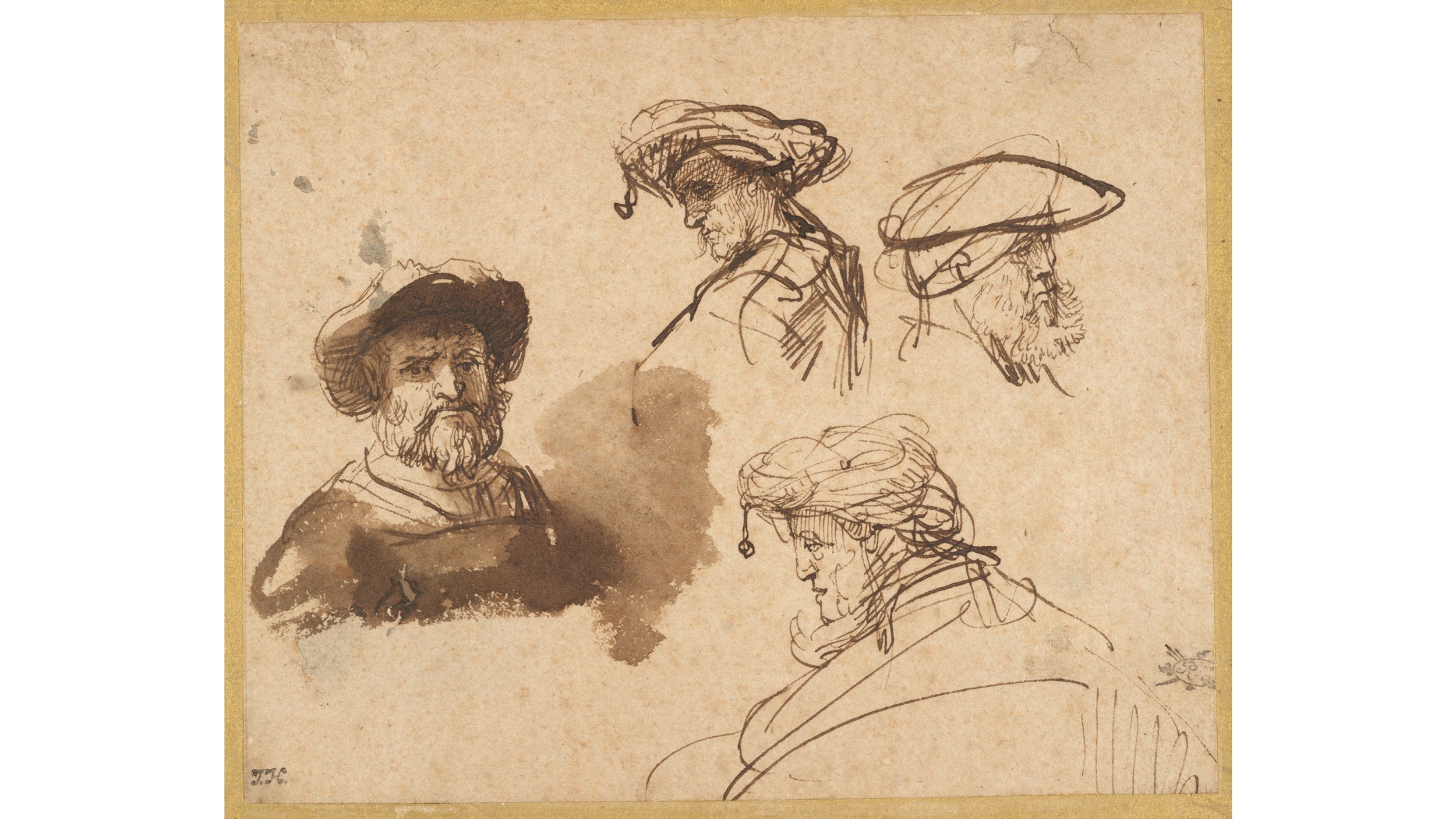

“Four Studies of Male Heads” is part of an intimate installation at the Harvard Art Museums.

Photo: Harvard Art Museums; © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Connecting with a masterpiece

Rembrandt drawing at Harvard Art Museums offers a close look at artist’s hand

Oil, ink, bronze, pastel. No matter the medium, art is an invitation to look close, learn, connect with an artist, and explore the creative process of admiration, influence, and evolution.

“Portrait of an Old Man” by the Dutch master Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn is a master class unto itself.

The oil painting, which graces the walls of the Harvard Art Museums, reveals much about both technique and emotion. Curators say the piece, completed in 1632, showcases “the dramatic lighting and painstaking description and level of detail and texture that inform his early work.”

This summer the evocative portrait will hang alongside one of Harvard’s newest Rembrandt holdings, “Four Studies of Male Heads,” an early drawing in brown ink that connects visitors even more closely with Rembrandt’s hand — a hand that inspired countless others.

“The impressionists, and many 19th-century artists such as James McNeill Whistler, looked to Rembrandt as a model,” said Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot Director of the Harvard Art Museums Martha Tedeschi on a recent afternoon in the museums’ airy Art Study Center. “Vincent van Gogh called Rembrandt a magician and pointed to his ability to capture mysterious aspects of the human psyche and human life in a way that words in any language couldn’t. Many found him to have a kind of depth, a perception that was incredibly rare.”

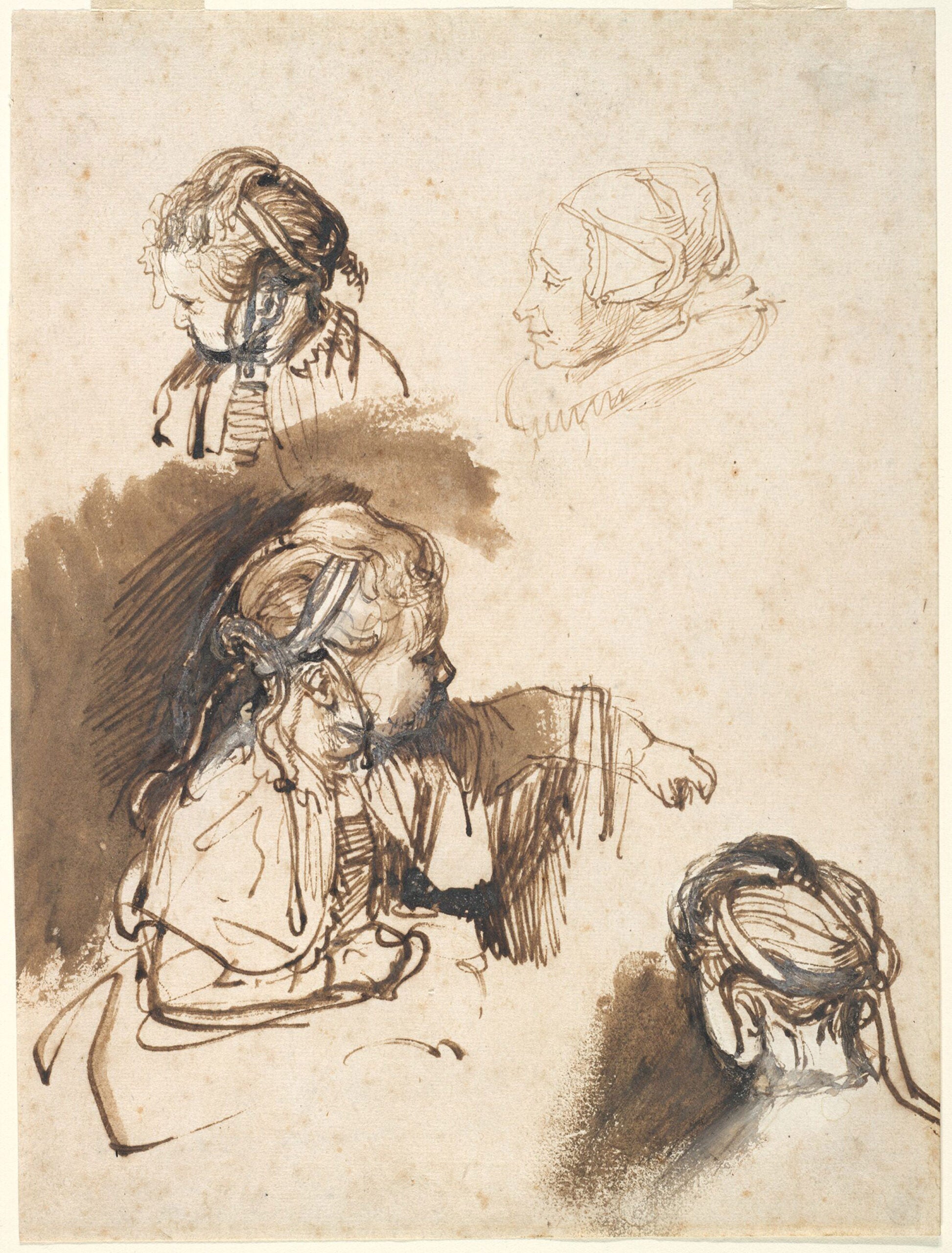

Rembrandt’s “Three Studies of a Child and One of a Woman,” c. 1638–40. “Portrait of an Old Man,” 1632.

Photos: Harvard Art Museums; © President and Fellows of Harvard College

The drawing, included in a 2017 promised gift of more than 300 16th- to 18th-century Dutch, Flemish, and Netherlandish drawings from the Maida and George Abrams collection, and then outright gifted in 2018, will be part of the intimate installation “Rembrandt and the Performance of Drawing,” featuring two of Rembrandt’s drawings, and two prints in a display timed to the 350th anniversary of the artist’s death.

For Tedeschi, as for many other art enthusiasts, drawings hold special appeal. Unlike paintings, where an artist’s early composition or color choice may have been obscured by layers of oil added over time, in a drawing one can see clearly “the direct connection between the decisions being made by the artist and the hand,” said Tedeschi. “For me that’s why drawings are so special, particularly when you are looking at a Rembrandt drawing like this, where his process is laid bare.”

In “Four Studies of Male Heads,” Rembrandt “didn’t try to obscure the lines he’d made the first time,” said the museums’ director, pointing to a redrawn hat on the figure Rembrandt sketched in the upper right corner of the page. “He allows us to see the process and that’s incredibly important.” Also important, she added, was Rembrandt’s ability to pick a decisive feature — the slump of a shoulder, the melancholic expression on a face — “and bring it alive.”

While some suspect “Four Studies of Male Heads” was used as a teaching tool for his students, others feel the drawing’s complexity implies it was a finished work intended for sale. “Rembrandt was beginning to understand that there were connoisseurs who really appreciated being led into that artistic practice,” said Tedeschi, “and that a sheet like this would give a drawings collector of the period a feeling of intimacy with the artist.”

Though Rembrandt inspired generations of artists, he, like many of his contemporaries including amateur Dutch draftsman Jan de Bisschop, often looked to others for inspiration.

Known for copying Italian paintings from the Renaissance, Mannerist, and Baroque periods, De Bisschop’s drawing “Simon Magus Rebuked by Saint Peter,” which is also part of the museums’ collection, is a reproduction of Italian artist Francesco Vanni’s most famous painting, commissioned by Pope Clement VIII as part of a monumental altarpiece in the basilica of Saint Peter, said Susan Anderson, a curatorial research associate at the museums and a scholar of Dutch, Flemish, and Netherlandish drawings. “Today, the Vanni painting suffers from significant damage, making De Bisschop’s drawing an important record of its original appearance,” Anderson said.

More like this

Some artists looked closer to home for their creative spark. Dutch artist Jacob Matham’s meticulous pen drawing “Portrait of a Man” reflects the influence of his stepfather and teacher, Hendrik Goltzius, a painter and draftsman who preceded Rembrandt as an iconic master draftsman of the Dutch Golden Age. Goltzius’ highly finished pen drawings imitated the fine lines found in engravings, and were widely admired.

“This notoriously demanding technique, which required the draftsman to work with no corrections, was a career-long preoccupation for Goltzius. Matham’s work in this manner is clearly indebted to his master’s example,” notes the entry for the work in the special collections section of the museums’ website focused on drawings from the age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt.

Museum staff say that the collections online tool can be a valuable resource for those looking to explore chains of influence. It features a range of details and information about the 839 works currently listed. It also highlights Harvard’s extensive holdings at a time when art from the Dutch Golden Age has taken center stage in Boston. In addition to Abrams’ extensive Harvard gifts, the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) received a trove of Dutch and Flemish art in 2017 from three different donors. In 2020 the MFA will launch its Center for Netherlandish Art, devoted to scholarship on the Dutch and Flemish art of the early modern period. And in 2021, the Harvard Art Museums will feature an exhibit on Dutch landscapes from the Golden Age.

Above all, said Anderson, who worked on the museums’ special collections online tool, “our hope is to just inspire interest in this material,” and to get people looking.

“Rembrandt and the Performance of Drawing” will be on view in the museums’ second-floor 17th-Century Dutch and Flemish Art gallery through Nov. 19.

For a list of accompanying gallery talks, click here.

The special collection “Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: The Complete Collection Online” is searchable via the museum’s website.