Neil Armstrong and the lunar module are reflected in Buzz Aldrin’s visor as he stands on the moon.

Archival images courtesy of Houghton Library

Exhibit charts history of Apollo 11 moon mission

Houghton Library show marking 50th anniversary of moonwalk includes NASA artifacts

As the 17th century’s most famous Italian astronomer surveyed the heavens, he likely never dreamed a rocket shooting fire would one day power people up among the stars he eyed through his telescope, or that his work would help guide a ship to the moon.

But Galileo Galilei’s observations would become a key link in the chain of scientific research and discovery fundamental to our understanding of the universe and our drive to explore it.

That scientific continuum is at the heart of a new Houghton Library exhibit connecting early celestial calculations to the Apollo 11 mission that put two American astronauts on the lunar surface 50 years ago this July. “Small Steps, Giant Leaps: Apollo 11 at Fifty” features gems from Harvard’s collection of rare books and manuscripts as well as NASA artifacts from an anonymous lender and Harvard alumnus, many of which were aboard the spaceship that left Earth’s orbit in 1969.

“The show gives you a picture of what happened in 1969 but it also connects those historic events to the scientific tradition that stretches back several centuries,” said John Overholt, the library’s curator of early books and manuscripts. “That kind of context is very much what Houghton’s mission is all about.”

Eight glass-topped cases in the building’s first-floor Edison & Newman Room contain material from Houghton’s collection, including a number of treasures directly related to the Apollo flight and about a dozen “real classics in physics and astronomy,” said Overholt, who curated the new show.

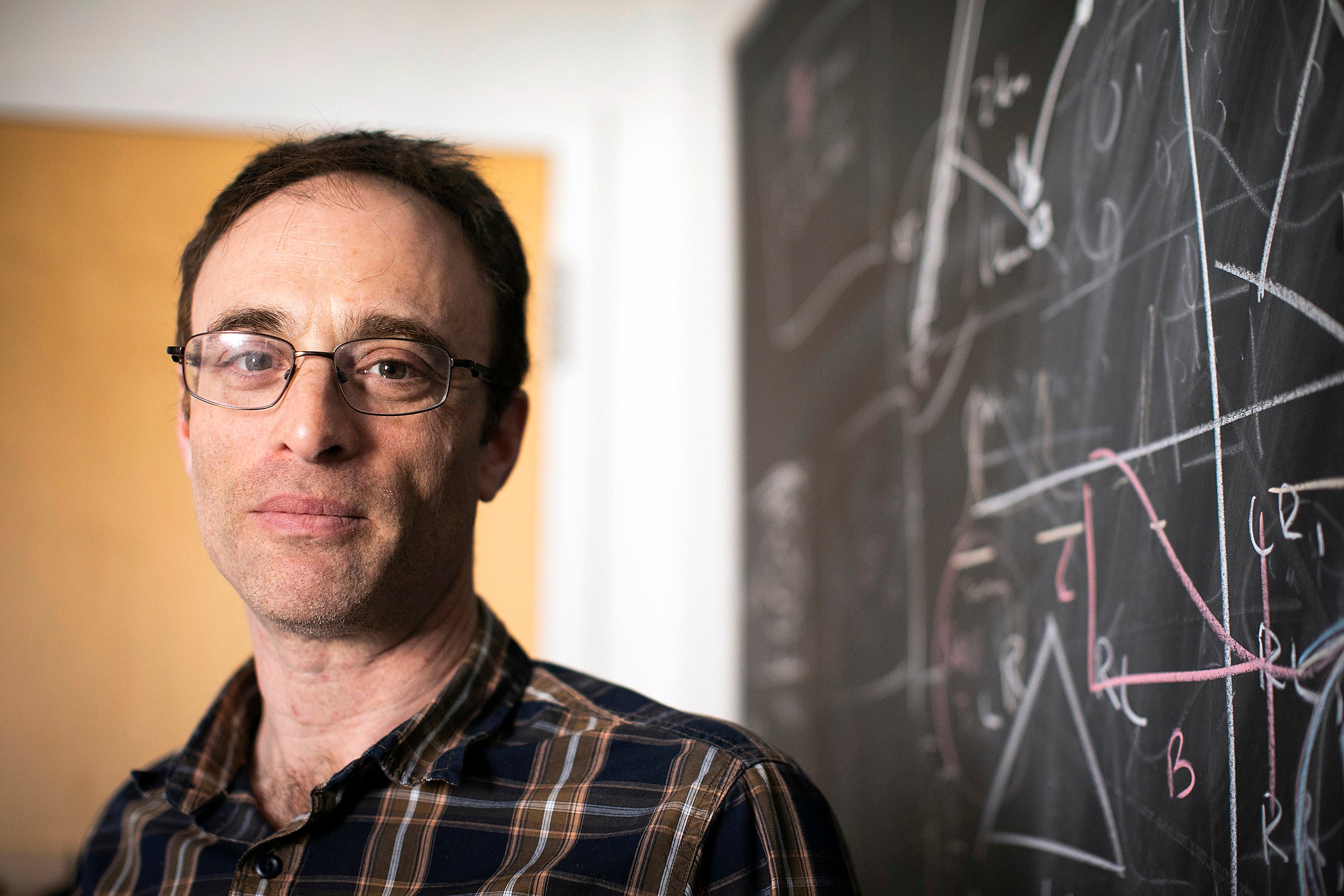

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“The show gives you a picture of what happened in 1969 but it also connects those historic events to the scientific tradition that stretches back several centuries.”

John Overholt, Houghton’s curator of early books and manuscripts (pictured above)

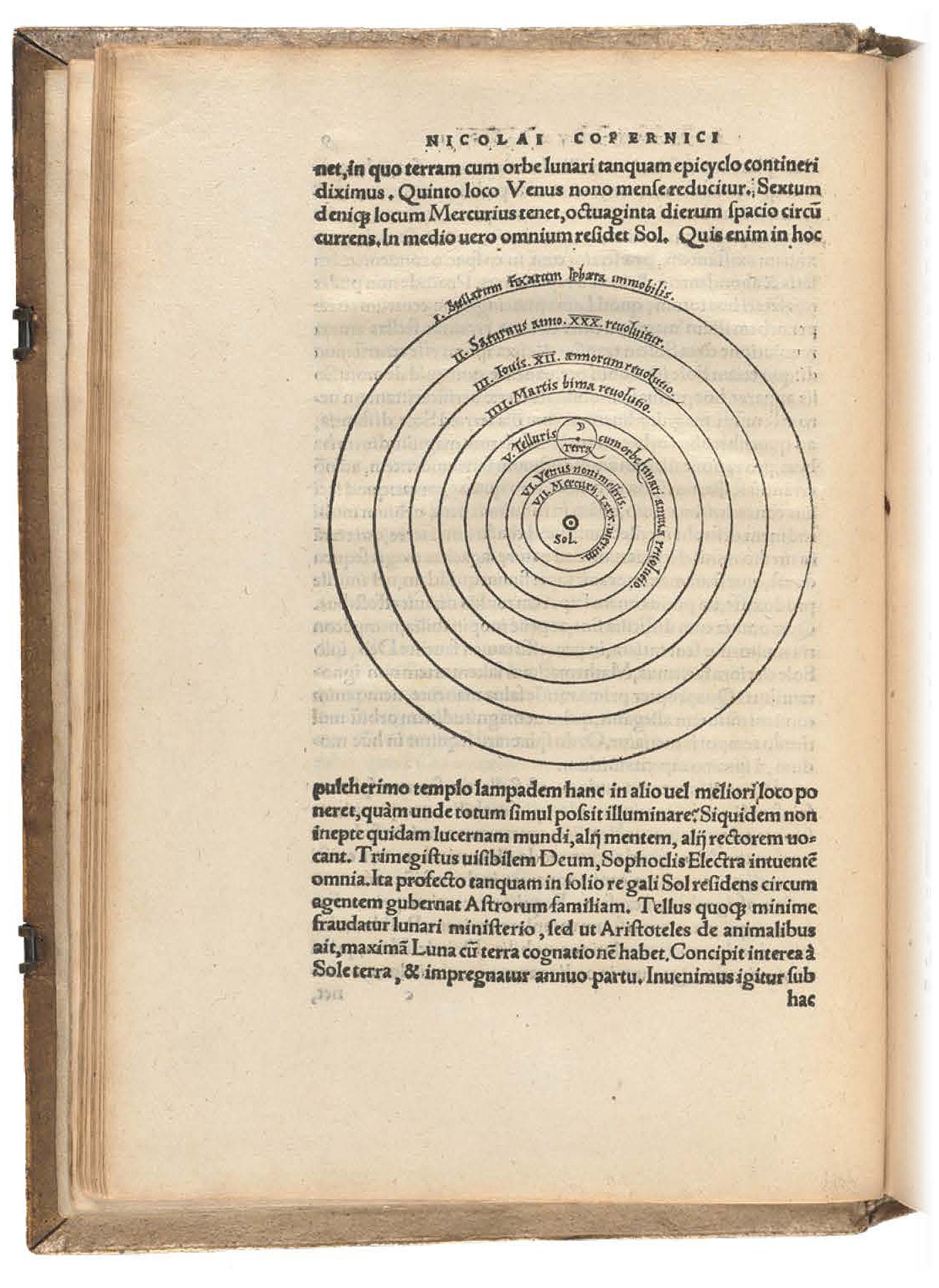

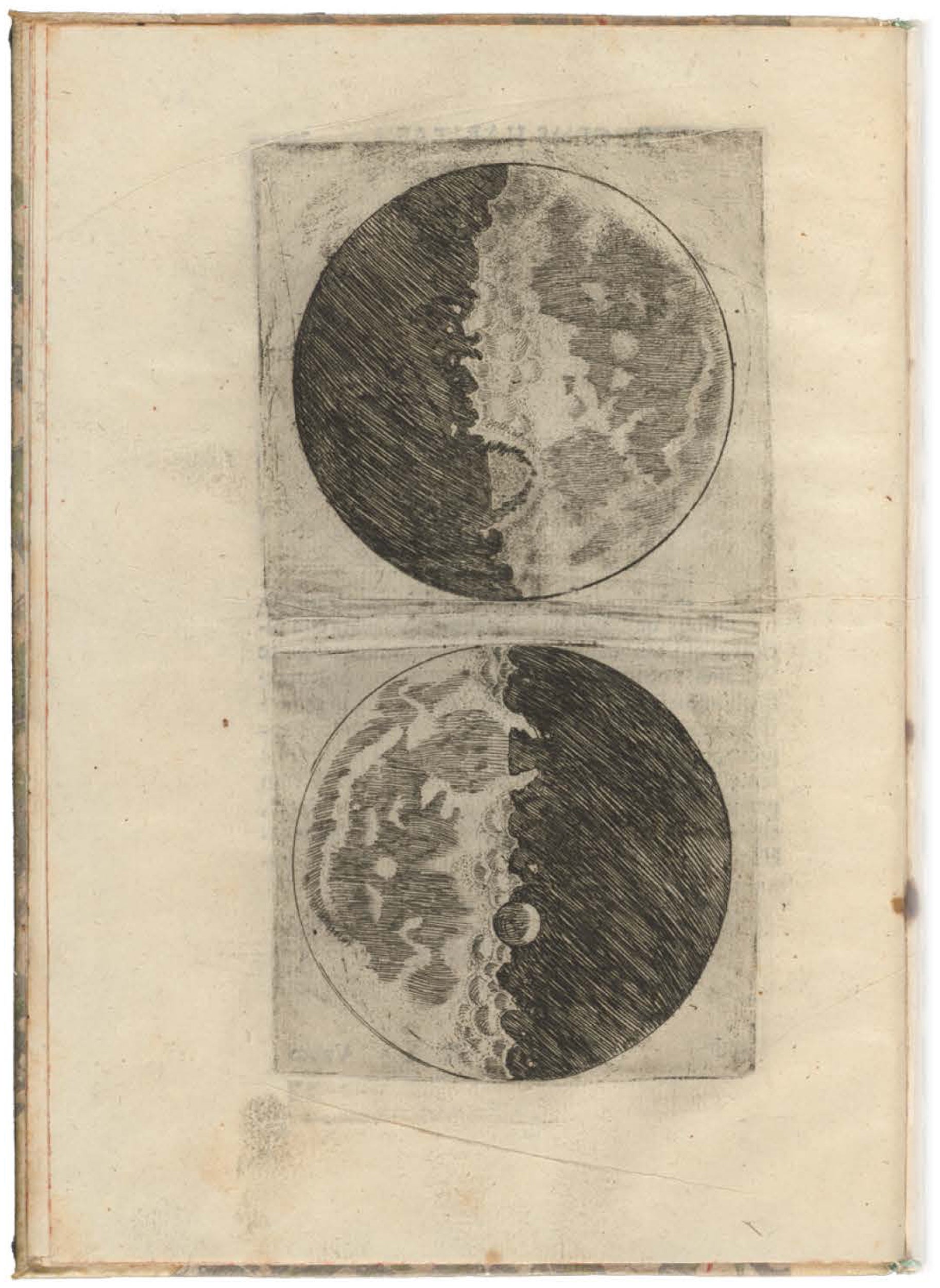

A diagram from “On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres” by Nicolaus Copernicus places the sun at the center of the solar system instead of the Earth; Galileo’s “Siderius Nuncius” contains the very first images of the moon as observed through a telescope.

Among the early masterworks on view is an edition of “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” (“On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres”) by Nicolaus Copernicus. The groundbreaking book by the Renaissance-era scholar upended the then-accepted order of the universe, placing the sun at the center of the solar system instead of the Earth.

A copy of Galileo’s book “Siderius Nuncius,” containing the very first images of the moon as observed through a telescope, is also on display. “It is just a breathtaking moment for everybody in the time period,” said Overholt of Galileo’s seminal text. “It lets them see the moon up close and shatters the Aristotelian myth that it’s just a perfect smooth sphere, proving instead that its landscape looks very familiar to observers on Earth.”

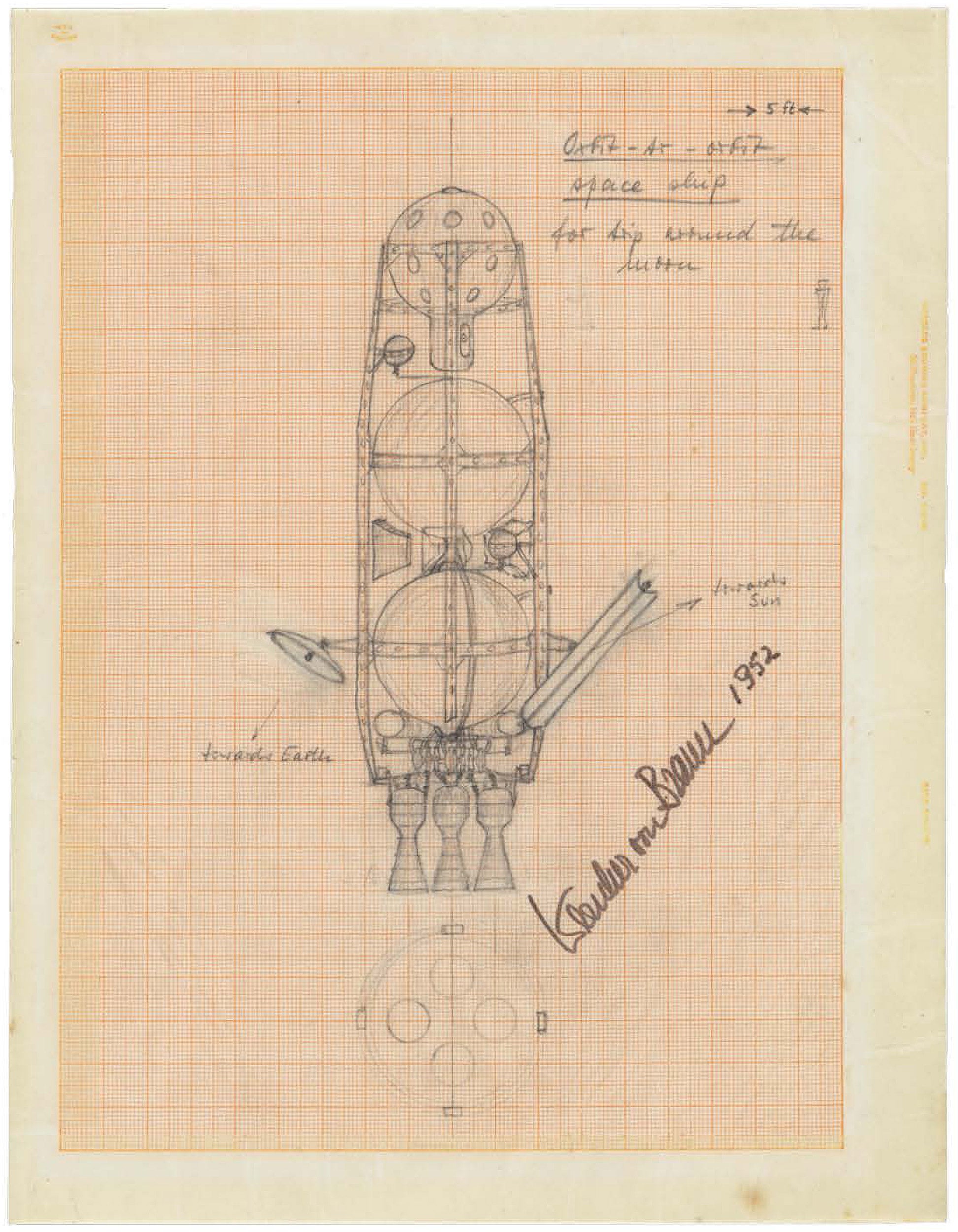

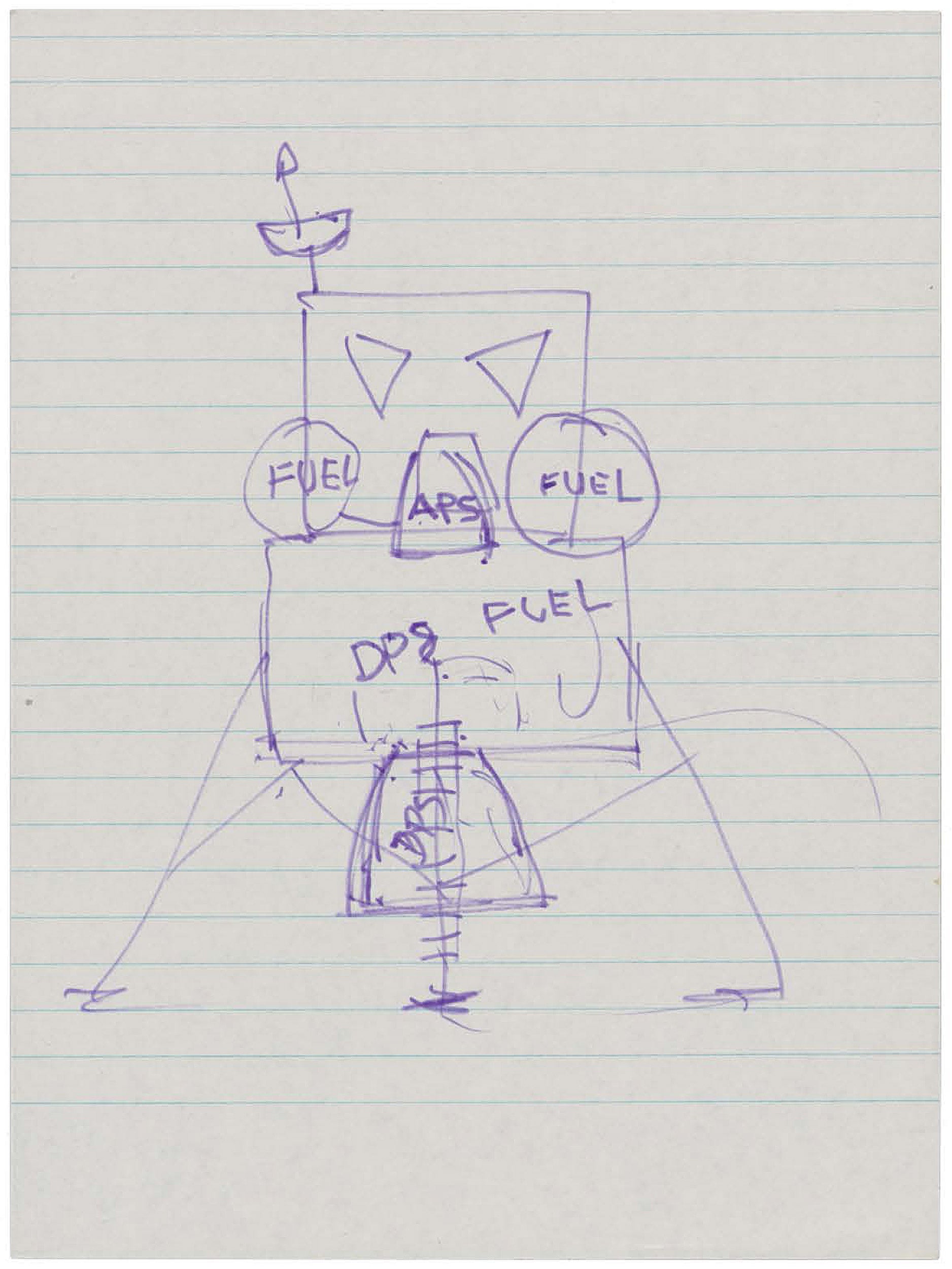

An early rocket drawing by space architect Wernher von Braun; a sketch Neil Armstrong made of the lunar module to explain the upcoming Apollo 11 mission to his father.

Other early mathematical advances that helped pave the way to the stars include those contained in a 1687 volume of Isaac Newton’s “Principia Mathematica.” In his text, considered critical to the development of modern physics and astronomy, Newton outlined his three laws of motion and defined elliptical orbits and gravitation. The work “deals specifically with the eccentricities of the moon’s orbit, which are crucial to eventually calculating an accurate path for spacecraft in the 20th century,” said Overholt.

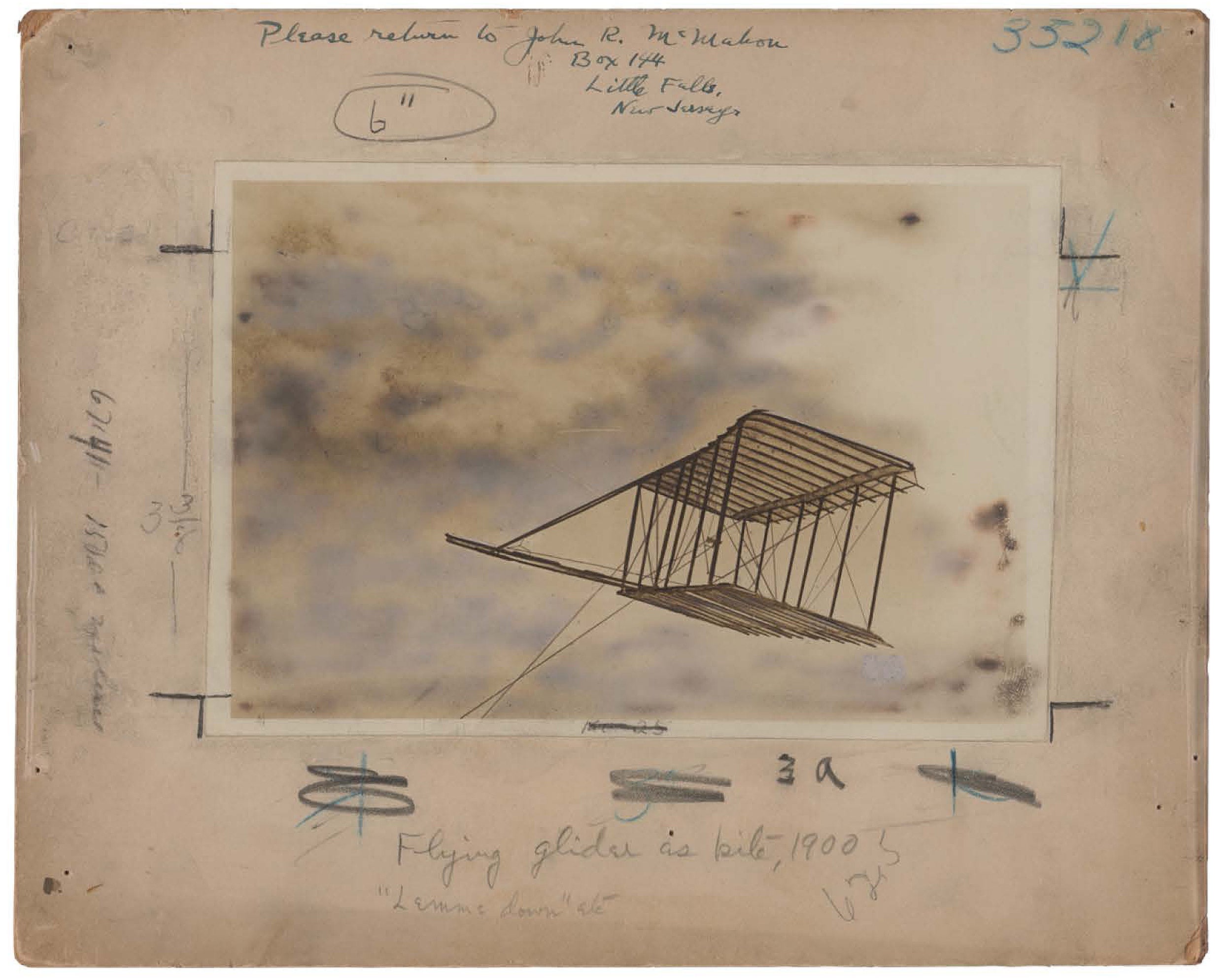

Of course, space travel powered by super-boosted rockets was preceded by simpler aircraft. In one case, articles by aviation pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright documenting their first flights in Kitty Hawk, N.C., highlight the early history of flight. Rocket-related ephemera include the first image of Earth taken from space courtesy of a V-2 rocket designed by Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun. Secretly employed by the U.S. Army after World War II, von Braun would go on to become the director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and chief architect of the Saturn V launch vehicle that blasted American astronauts beyond Earth’s gravitational pull.

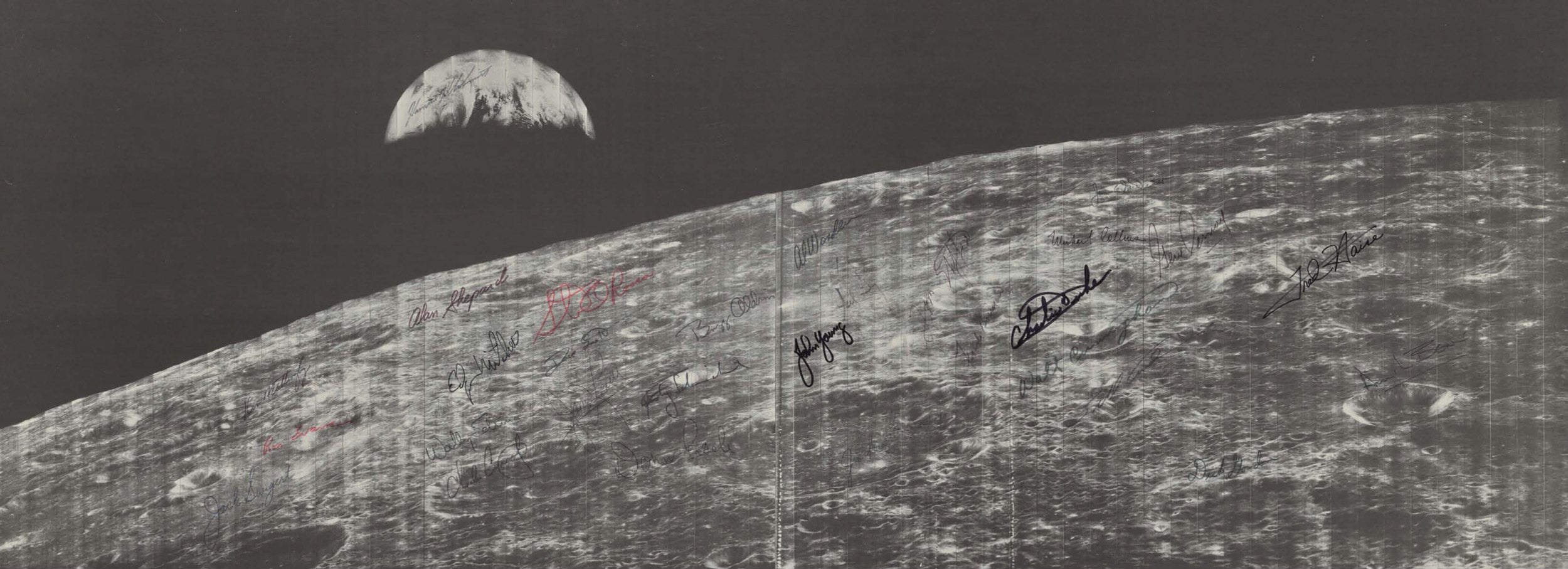

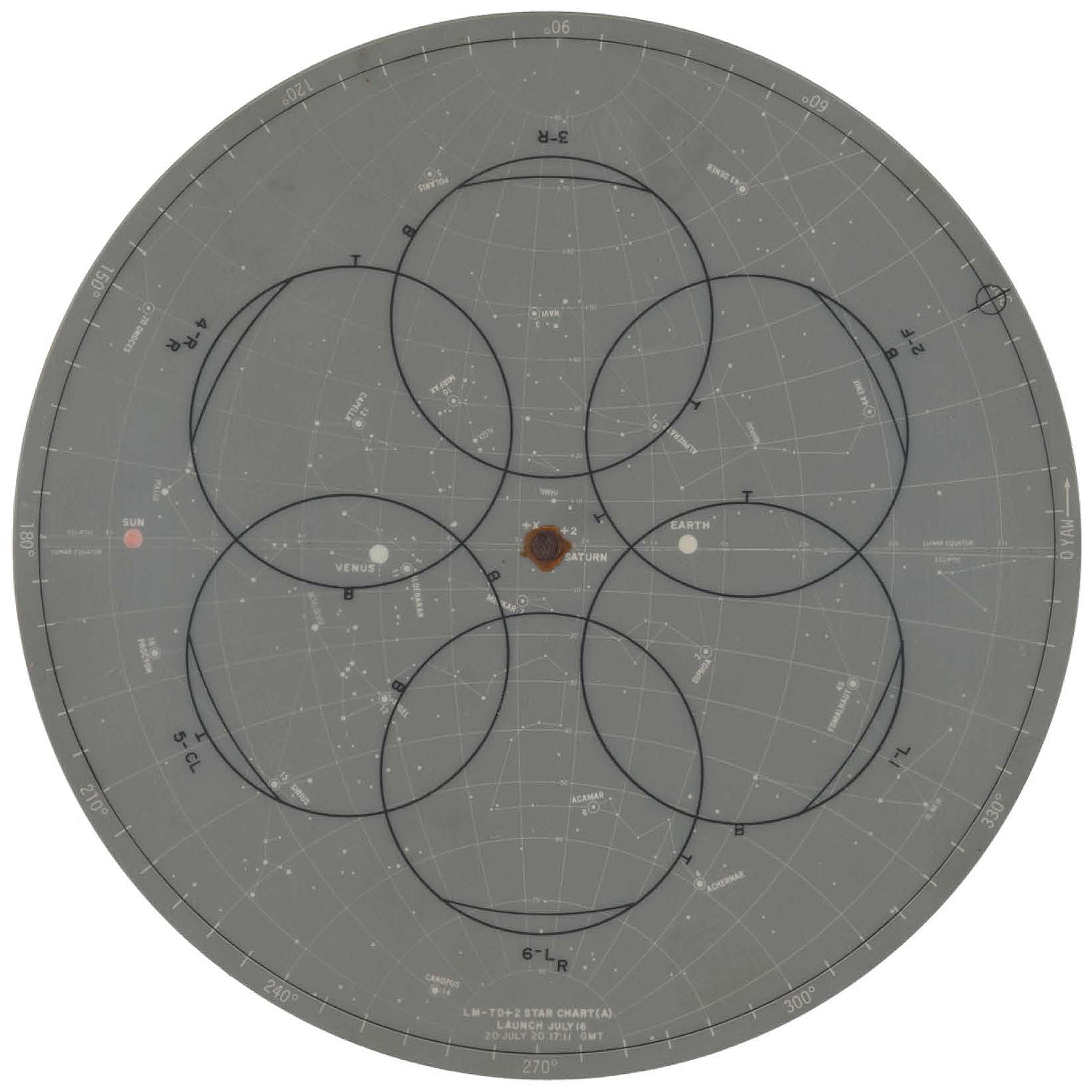

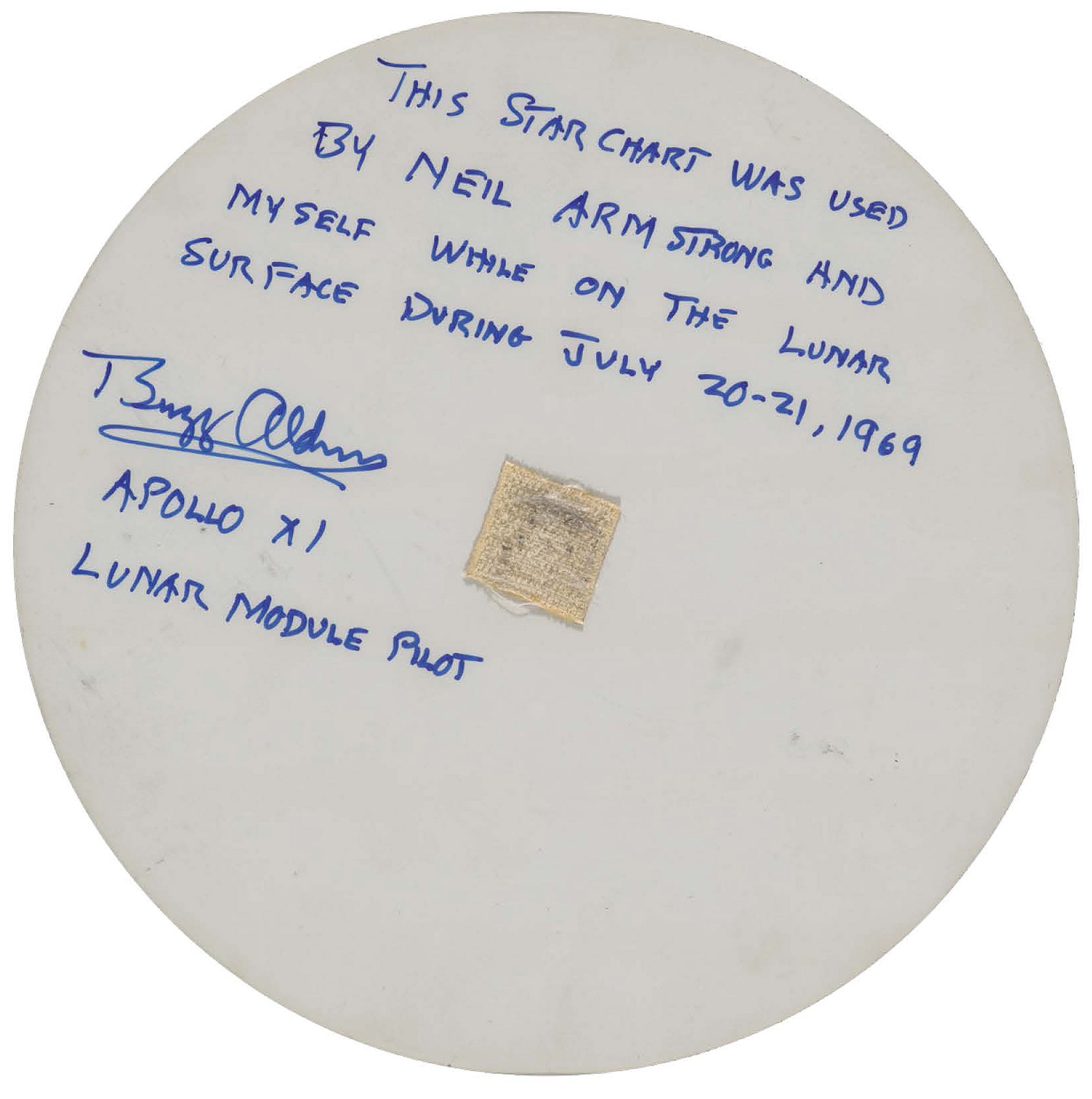

Both sides of the star chart the Apollo astronauts consulted to gain their bearings. The Velcro in the back picked up moon dust.

![Flight plan inscribed with Neil Armstrong's famous line: “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”](http://news.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/flightplan.jpg)

Then there are the items that landed on the lunar surface. “Awe-inspiring” aptly describes the actual star chart the Apollo astronauts consulted to gain their bearings. “It was the first time someone was looking at the stars and not standing on the Earth,” said Overholt of the map that returned from space with moon dust embedded in Velcro affixed to its back.

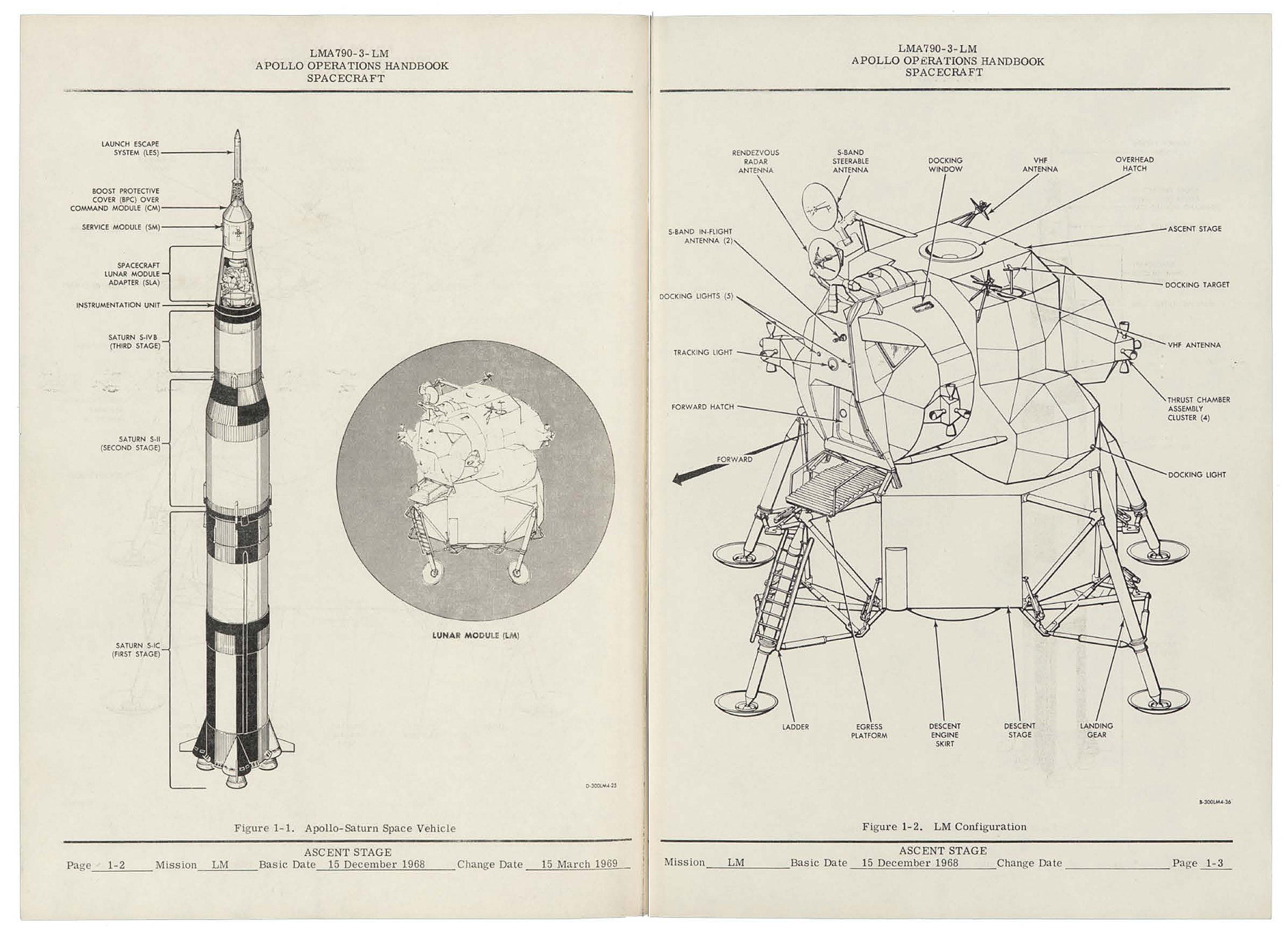

Other treasures connected to the historic mission include a sheet of paper from the required quarantine that followed the astronauts’ splashdown in the Pacific Ocean on July 24. Neil Armstrong, the commander of Apollo 11 and the first person to walk on the moon, scrawled on the page his instantly famous line: “One small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” (Whether he actually uttered the “a” has long been a topic of debate, but Armstrong insisted he did and included it in the inscription.) Technical manuals offer an inside look at the complex and complicated process of evaluating error codes; the astronauts had to act quickly as they approached the moon to determine if warning signals meant abort.

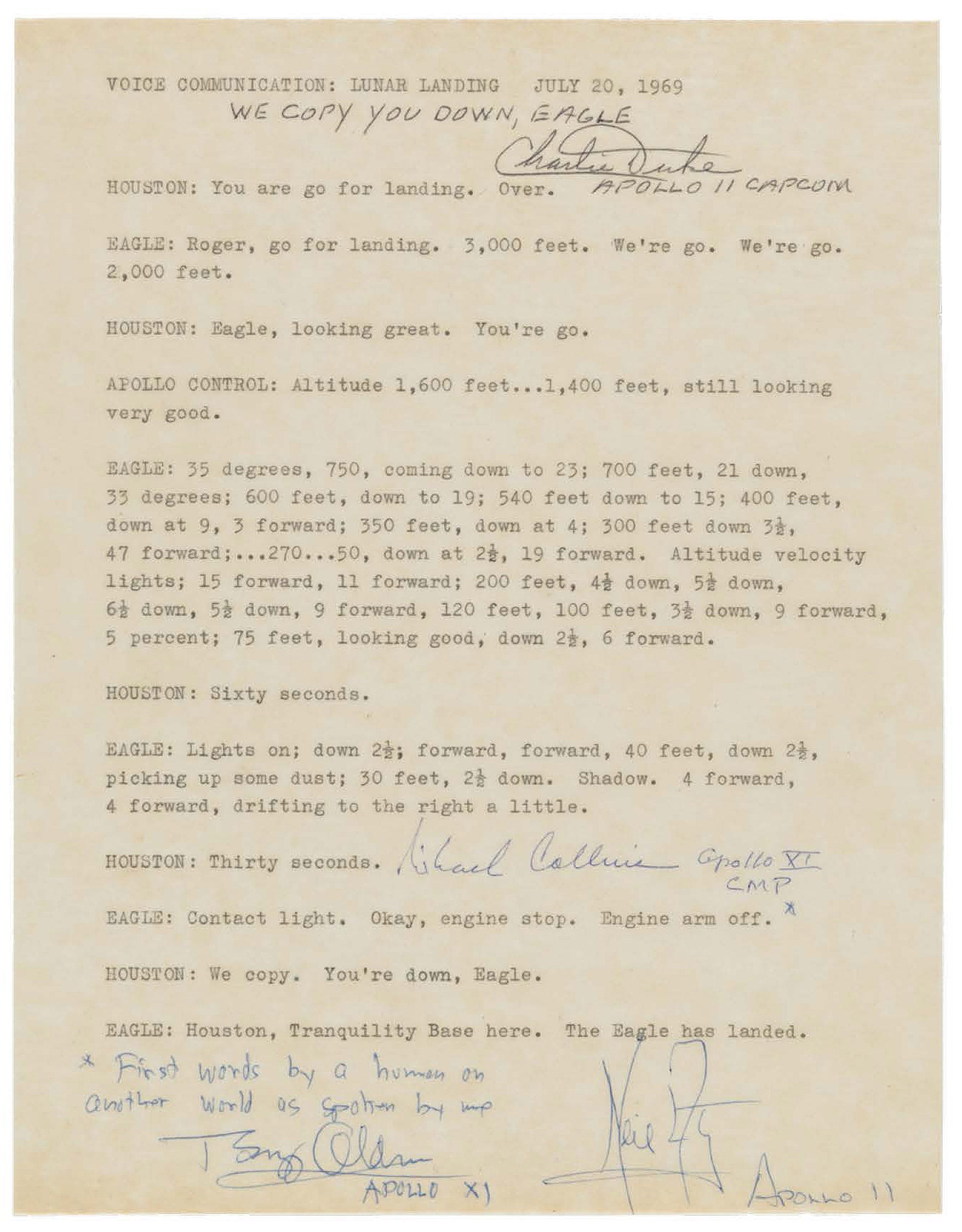

Image 1: Transcript chronicles tense moments of Eagle landing. As Eagle approached the lunar surface, Neil Armstrong realized that it was headed for a boulder-strewn crater. He manually guided the lunar module to a smoother area, consuming precious fuel in the process. When it finally touched down in the Sea of Tranquility, Eagle had fewer than 30 seconds of fuel remaining. After Aldrin informed Houston, “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed,” Duke replied, “Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.” Image 2: Operation handbook for the Eagle.

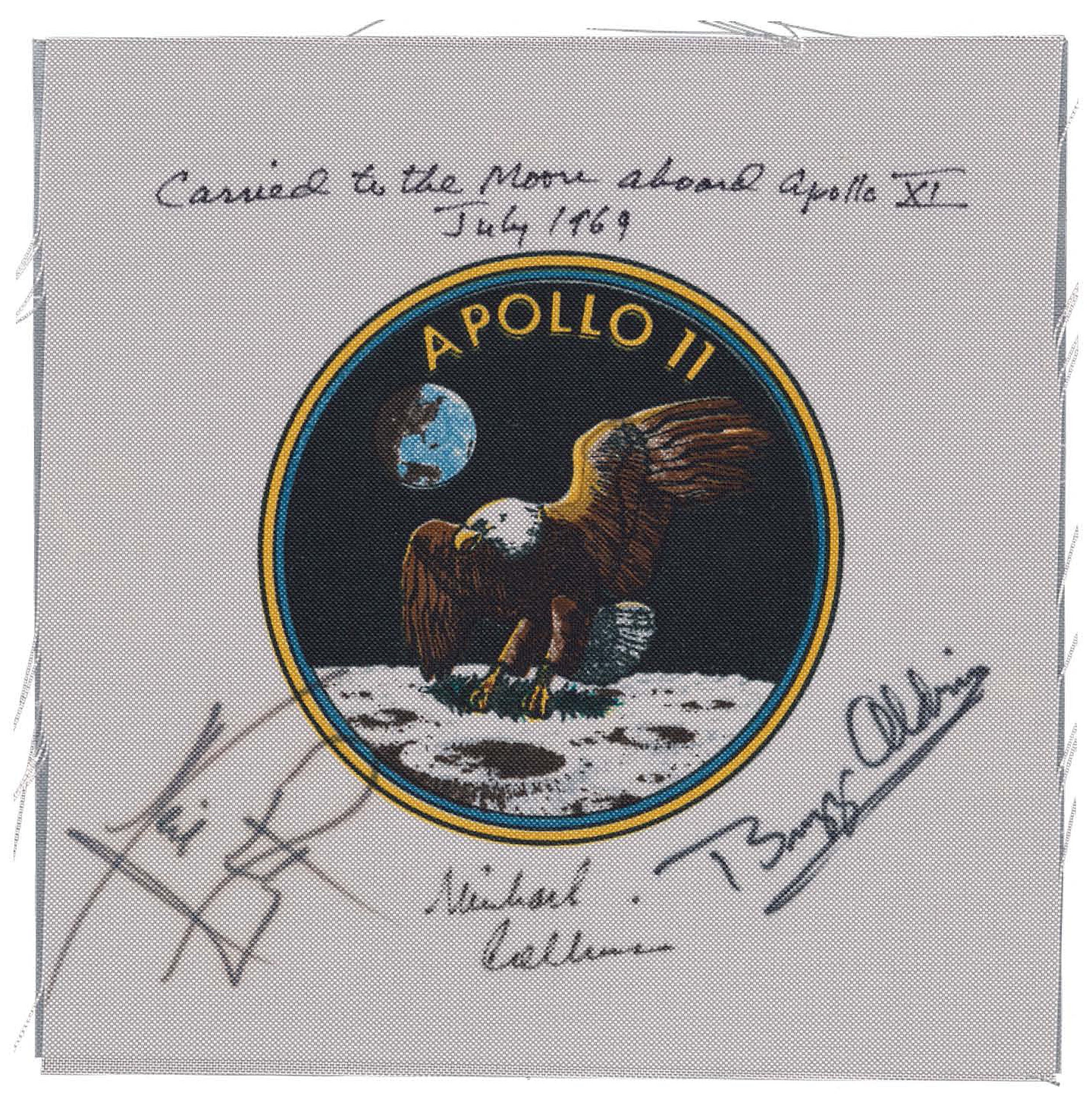

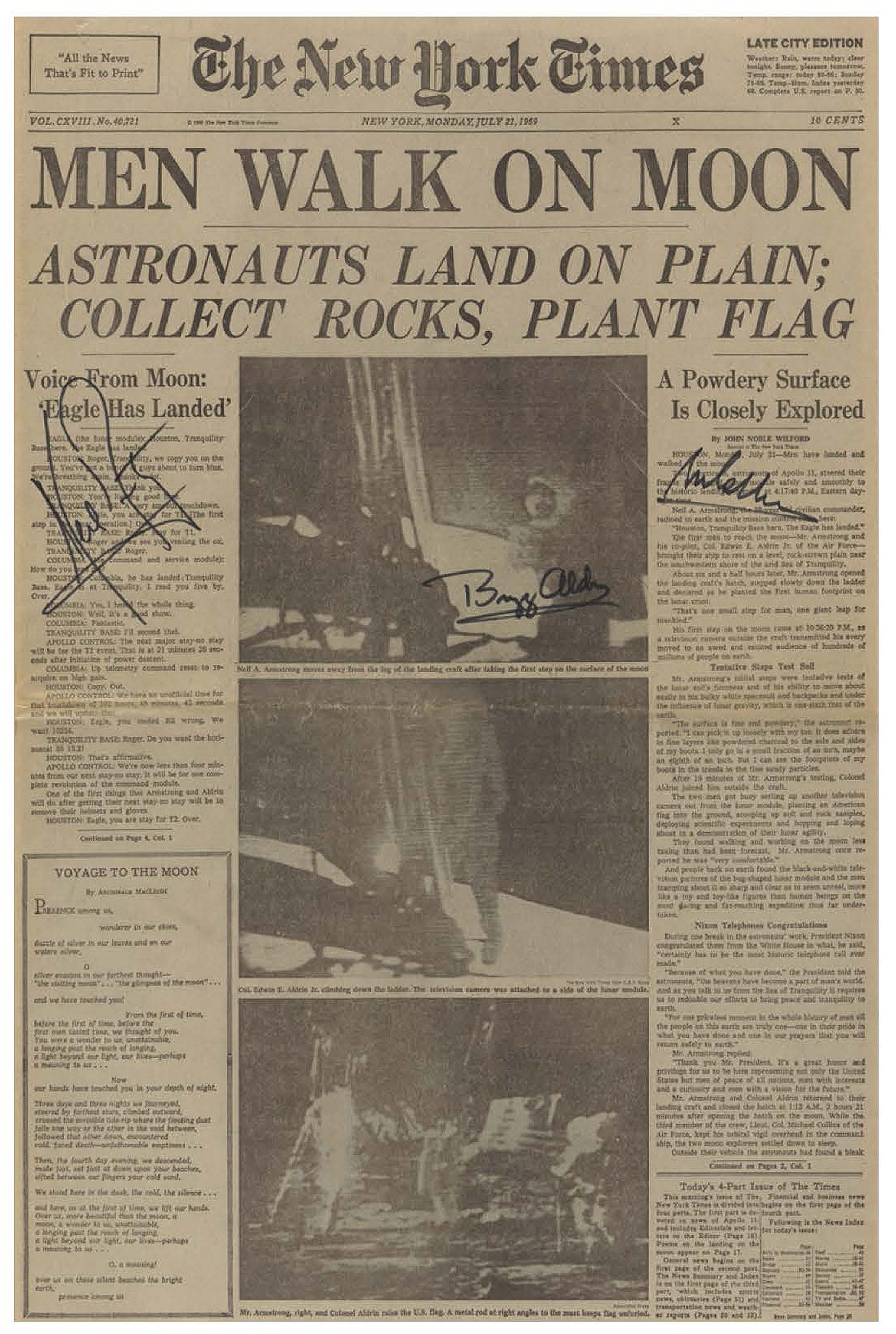

Apollo 11 mission patch; July 21, 1969, front page of The New York Times.

For Overholt, the scientific through line is the show’s defining feature.

“The exhibit shows that this historic event didn’t happen in isolation,” he said. “It took centuries of research and discovery to develop the knowledge of physics and the understanding of what the moon was like and how we might create a vehicle that could travel there. By putting those two halves together I think we are offering visitors that complete picture.”

“Small Steps, Giant Leaps: Apollo 11 at Fifty” is on view through Aug. 3. For more information and a list of programs connected to the exhibit, click here.