President Larry Bacow speaks about how universities can address inequalities.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

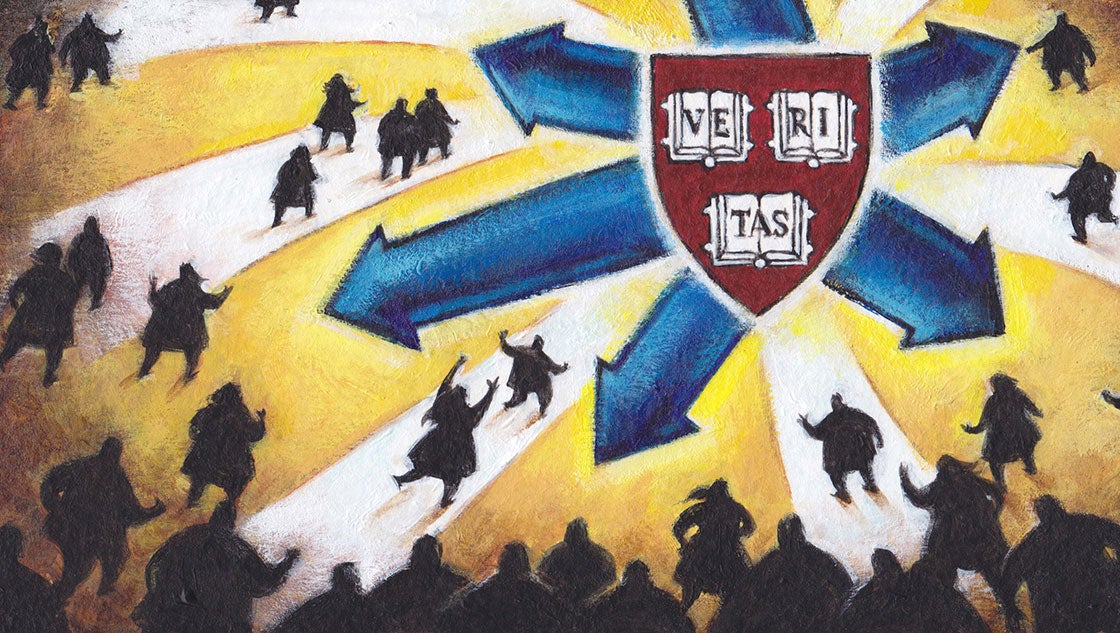

Bringing back hope

Bacow addresses universities’ role in tackling inequality and declining social mobility

With their many scholarly resources, universities can play a major role in tackling the growing problems of income inequality and declining social mobility that are creating deep divisions and eroding social capital in the U.S., says Harvard President Larry Bacow.

“Universities have an important role to play, not just by shining a light on the structural issues, which we need to address, but also by developing new technologies and industries that can be the engine of economic growth,” Bacow said Thursday night in conversation with Bridget Terry Long, dean of the Graduate School of Education, at the annual Malcolm H. Wiener Lecture hosted by the Institute of Politics.

“Inequality is corroding society,” said Bacow. “The growing inequality and the lack of opportunity for those at the bottom of the economic strata is destroying hope, and when hope is gone, society changes in a big way.”

Bacow shared his views on the role universities can play in addressing economic opportunity and inequality with a packed classroom at the Harvard Kennedy School.

“In the last 10 years, we’ve recognized that it’s not enough just to admit people. We need to think hard about how we can really level the playing field, not just by giving people the opportunity for education but also by giving the opportunity for the same education while they are on our campus.”

Larry Bacow

Over the past two decades, universities have opened their doors to a broader cross-section of students, including those from low-income families, as part of efforts to address inequality and social mobility, he said. But there is more work to be done.

“In the last 10 years, we’ve recognized that it’s not enough just to admit people,” Bacow said. “We need to think hard about how we can really level the playing field, not just by giving people the opportunity for education but also by giving the opportunity for the same education while they are on our campus.”

Experts are growing concerned about the decline in social mobility in the U.S. Children born in the 1940s had a greater than 90 percent chance of doing better than their parents, but for children born in the 1970s, that chance dropped closer to 50 percent, said Long.

Bacow talked about Pontiac, Mich., where he grew up, to describe how that decline is breeding hopelessness. In the late 1960s, he said, Pontiac had three General Motors factories and people knew they could have a comfortable middle-class life, with children almost guaranteed a better life than their parents. That’s not the case anymore, Bacow pointed out.

“When I graduated from high school in 1969, the population was 82,000,” he said. ”Now, it’s about 55,000. … One of the problems in Pontiac is that people don’t have hope. One of the things that economic mobility gives people is hope — the notion that the future is going to be better than the past.”

The conversation was disrupted early on by a group of 30 students from Divest Harvard. When the students refused to leave the stage and allow the event to continue, HKS dean Doug Elmendorf relocated the discussion.

After the talk resumed, Bacow referred to the protest. “Universities are places where people express opinions and they often express opinions sharply,” he said. “We have to expect that, for they will be dull places indeed if we went a semester or a year without some kind of protest, so I’m glad our students proved me right.”

For Jorge Calderon, a student at the Extension School who was in the audience, Bacow’s talk was a chance to learn that vanishing social mobility is a challenge to many countries and that universities can play a part to improve economic opportunity for all.

“When Bacow talked about Pontiac, that resonated with me,” said Calderon. “I come from a small town in El Salvador that had a cement factory where everybody worked, but when the factory closed and the civil war began, we lost everything. I immigrated here looking for opportunity, and being at this University … opens up many opportunities for a better life.”