“Human beings do not make good choices behind the wheel,” said Deborah Hersman at a Chan School panel discussion on the future of self-driving cars. “We’re hoping that machines will be better than us.”

Sarah Sholes/HSPH Communications

Checking the progress of self-driving cars

Wider adoption would make us safer, experts say, but accidents threaten to stall momentum

Participants in a panel Friday at the Harvard Chan School expressed confidence that self-driving cars will one day dramatically reduce road deaths in the U.S. — currently at 37,000 annually — but cautioned that we’re entering a transition period in which accidents involving such vehicles will almost certainly rise.

The discussion came a little more than a month after an Uber test of a self-driving car killed a pedestrian in Arizona. Also in March, the driver of a Tesla electric car traveling in autopilot died when the vehicle crashed.

About 1.25 million people die every year on roads worldwide. Cars free of drinking, texting, and other dangers will reduce that number, panelists said.

“Human beings do not make good choices behind the wheel,” said Deborah Hersman, president and chief executive officer of the National Safety Council. “We’re hoping that machines will be better than us.”

John Leonard, vice president of research for Toyota Research Institute, said that in addition to an automated driver’s exclusive focus on the road, the potential exists for advanced sensors that surpass human reaction time.

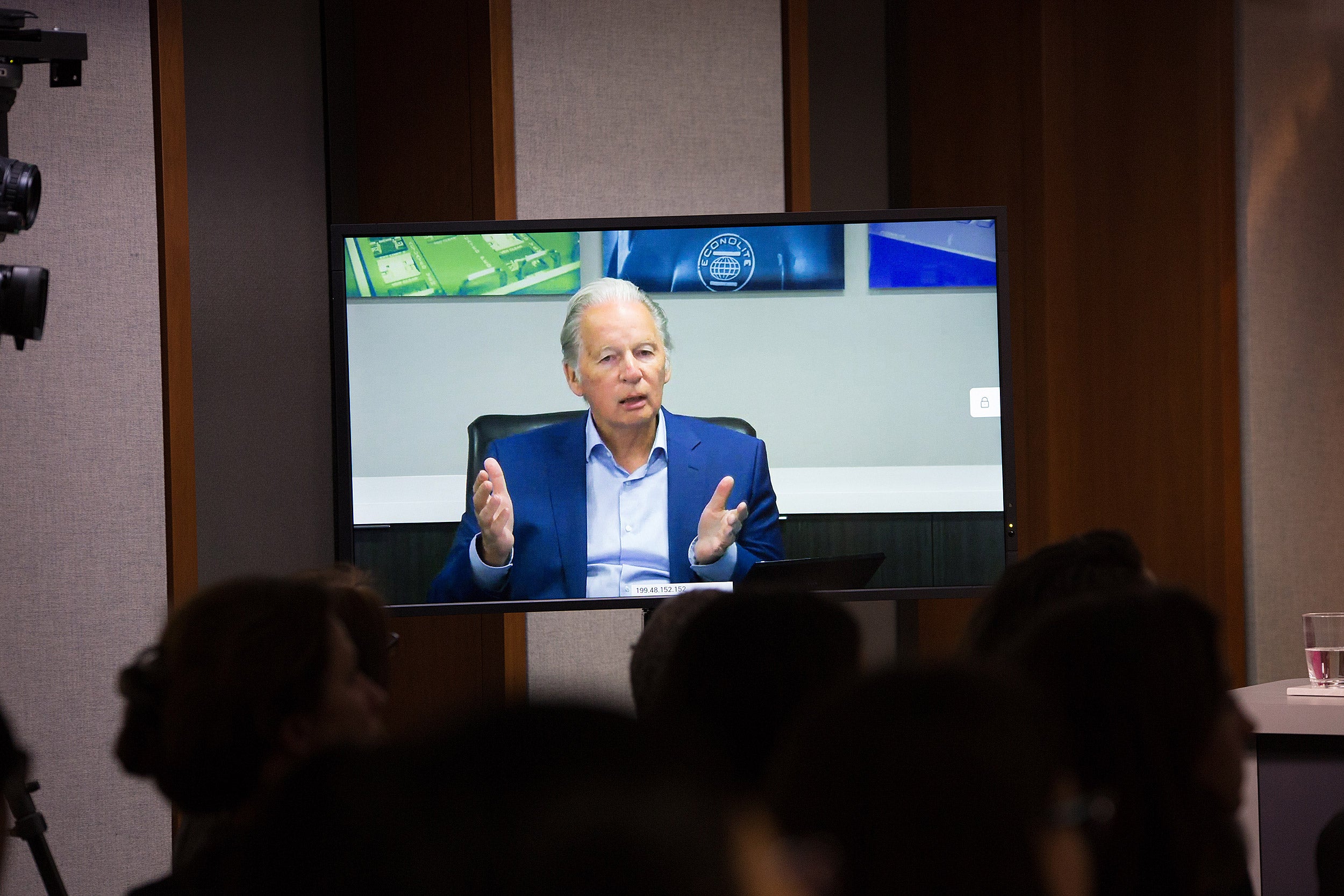

In addition to Hersman and Leonard, “Self-Driving Cars: Pros and Cons for the Public’s Health” featured Jay Winsten, Frank Stanton Director of the Harvard Chan School’s Center for Health Communication and associate dean for health communication, and Peter Sweatman, co-founding principal of CAVita, a consulting firm for autonomous vehicle companies. The discussion was moderated by David Freeman of NBC News Digital.

Though panelists Hersman (from left), John Leonard, Jay Winsten, and moderator David Freeman are hopeful for the potential of self-driving cars to reduce traffic deaths, Winsten predicts that fatalities involving self-driving cars will rise even as the number of overall road deaths falls.

Sarah Sholes/HSPH Communications

The rapid pace of autonomous-vehicle development is “the space race of our time,” Leonard said. Though different companies are using different technologies, there are basically two strategies in play, he said. One is the “chauffeur” approach, in which the car drives itself and humans are mainly out of the loop. The other requires a human to monitor the system and occasionally take the wheel.

Sweatman predicted that rollout will come in stages, with the pace of adoption influenced by whether early experiences are positive or negative. When automated vehicles begin to dominate the roads, infrastructure will be adapted to their capabilities, which will make roads even safer, he said.

Though safety is the main selling point of the new technology, Winsten predicted that fatalities involving self-driving cars will rise even as the number of overall road deaths falls. An important question will involve how the public reacts and whether a backlash against the technology stalls development, he said.

Data sharing will be important, the panelists said, partly through allowing firms to avoid repeating one another’s mistakes. Information gleaned not just from accidents but also from close calls can help law enforcement, regulators, insurers, and others, Hersman said.

Despite the excitement around the technology, Hersman and Winsten said fully self-driving cars aimed at consumers are still some time away.

“We’re not going to have these in our garage as a consumer anytime soon,” Hersman said.

Initial rollout will involve commercial fleets for ride-hailing companies such as Uber and Lyft, the panelists said, or will be in controlled environments, such as campus shuttle services.

The group listed options for drivers looking to improve car safety today. Studies have shown that automatic braking technology, blind spot warning systems, and other features can save 10,000 lives a year. These options are available mostly on higher-end models, which led panelists to note the potential for safety gaps between rich and poor drivers.

“We don’t want safety to be just for those who can afford it,” Hersman said.