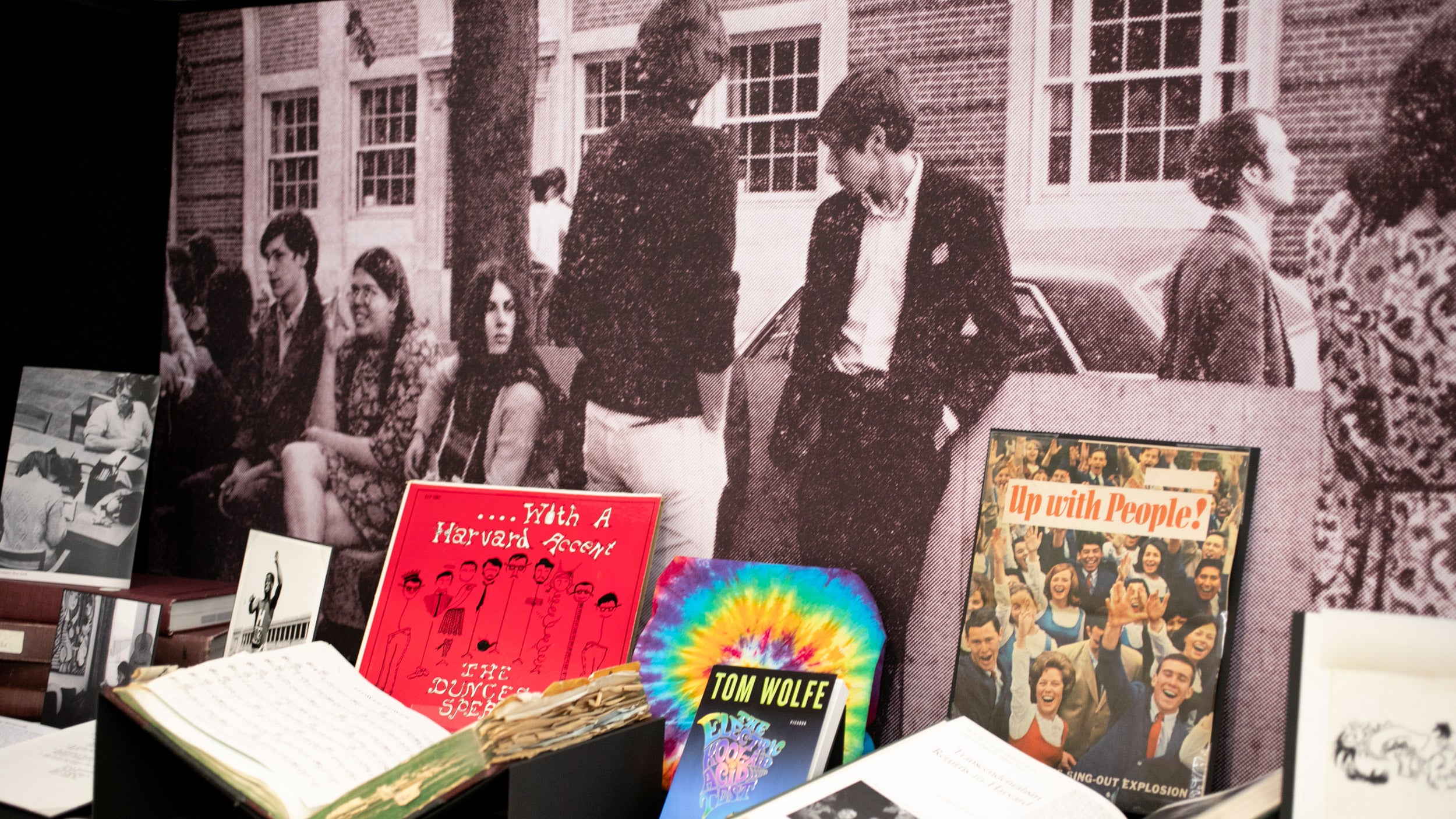

The “Harvard, 1968” exhibit at Pusey Library explores the events of that momentous year and beyond.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

A revolution, 50 years in the making

The Harvard and Radcliffe Class of 1968 returns to campus

“The student today is not the carefree, frivolous young person of yesterday’s college novels, and decisively he is not the acquisitive careerist we bemoaned as members of the silent and apathetic generation. Today’s student is a serious-minded, independent-thinking individual who seeks to analyze and understand the problems of our society, and find solutions to these problems which are in keeping with the highest traditions and values of our democratic system. … Today’s student is now recognized as a significant political actor with amazing power to influence the course of societies all over the world.”

— Coretta Scott King, Harvard Class Day speech, 1968

The 1960s were a decade of sweeping social and political change for the United States, and nowhere was that more evident than on its college campuses. From Civil Rights protests and the women’s movement to the Vietnam War, student activism played a major part in bringing about change, galvanizing people on campus and rippling outward to the country at large.

For the Harvard and Radcliffe Classes of 1968, the changes between 1964 and 1968 came sharp and fast, bookended by the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy ’40 in 1963, and Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy ’48 in 1968.

King, the first Class Day speaker invited by students, never made it to campus. He was assassinated on April 4, prompting the Class of ’68 to invite his widow, Coretta Scott King, to speak in his place. In remarks that seem as prescient today as they were then, she focused on the importance of actively participating in society and standing up for values, and the power of change.

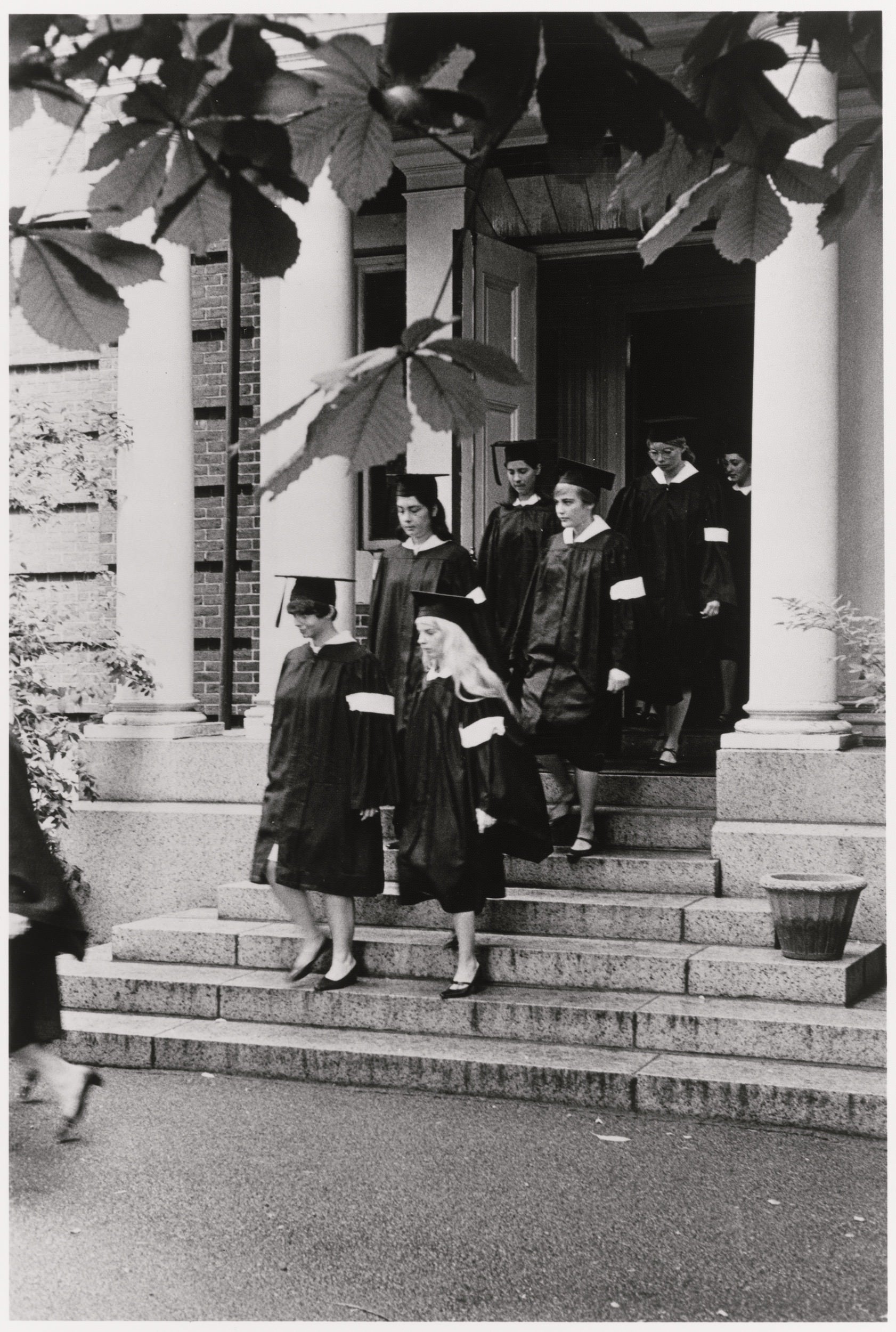

The method of choosing a Class Day speaker wasn’t the only change to graduation-related festivities. Breaking with Seven Sisters tradition, Radcliffe students refused to attend graduation — one of the last held in the Radcliffe Yard — unless they had a student speaker of their own.

“It could have been a dozen other people,” said Rachel “Ricki” Lieberman ’68, who was selected by her classmates to address graduates that year. “We came into a Radcliffe that was parietals and jolly up. When we left, Radcliffe was battling toward being co-ed, and that represented a sea change. We [wanted] a student speaker to address some of the tumult, angst, and danger of that period.”

Radcliffe’s 1968 graduates wore white armbands to indicate their opposition to the war and their sadness about the assassinations of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. earlier that spring.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Coming from a family of politically active Radcliffe graduates that included her mother and her aunt, Lieberman went on to a career that spanned the government and nonprofit worlds. A longtime volunteer for Hillary Clinton, who followed Lieberman’s lead as Wellesley College’s inaugural student speaker the next year, she credits her Radcliffe experience with helping her to build on the progressive values developed in her youth.

“There was just generally a sense that we were privileged to be [at Radcliffe], and [that] we had some obligation to society to use our opportunities,” she said. “Many of my ideals from the ’60s have not changed. I still go to demonstrations; I still support progressive causes. That’s something that I would encourage every student to include in their agenda. Take advantage. Volunteer. Find somebody whose values [you] can promote. Be as active and proactive as possible.”

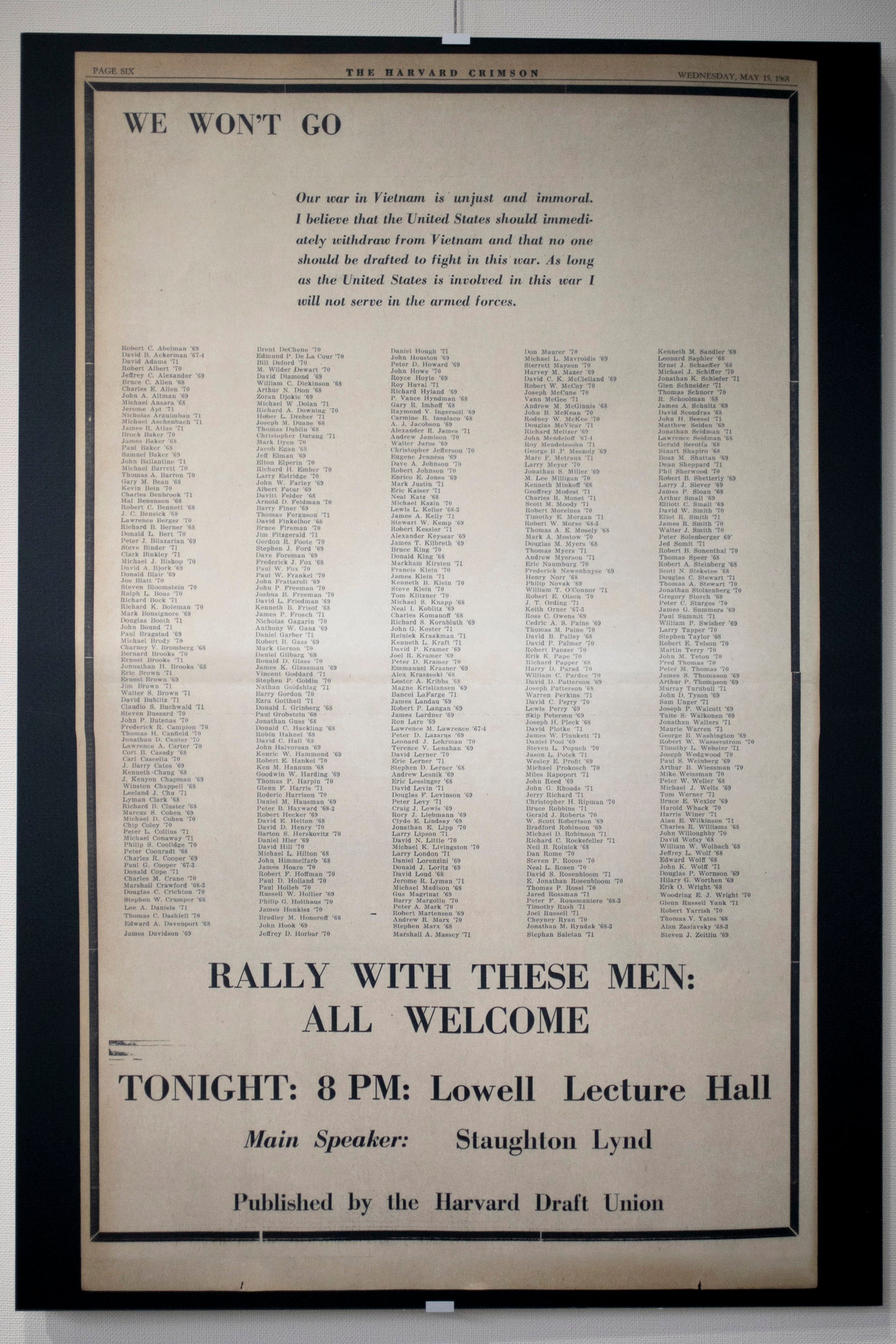

As the debate about American involvement in Vietnam raged across the country, college campuses became a flashpoint for opposition to the war, and sometimes for support. Harvard students were involved on both sides of the debate, serving in the armed forces but also participating in protests, sit-ins, teach-ins, and demonstrations.

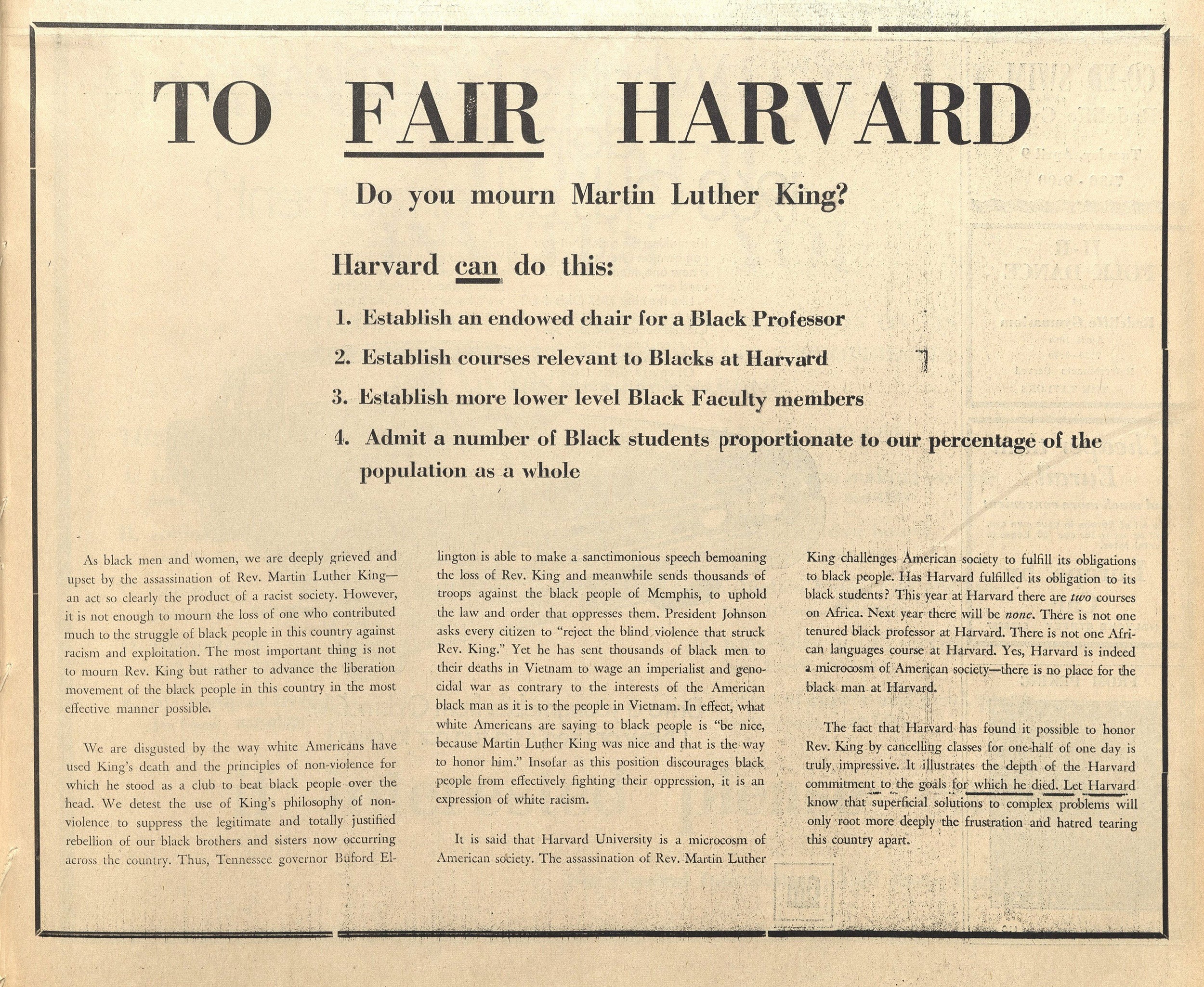

Image 1: A list of Harvard Vietnam War draft protesters. Image 2: After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the Harvard Association of African and African-American Students issued demands through the Crimson to establish an Afro-American studies program and hire additional black faculty members. Later that year, the first course in African-American history was taught at the University, followed by the establishment of the Department of Afro-American Studies and the Committee on African Studies in 1969.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives; Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

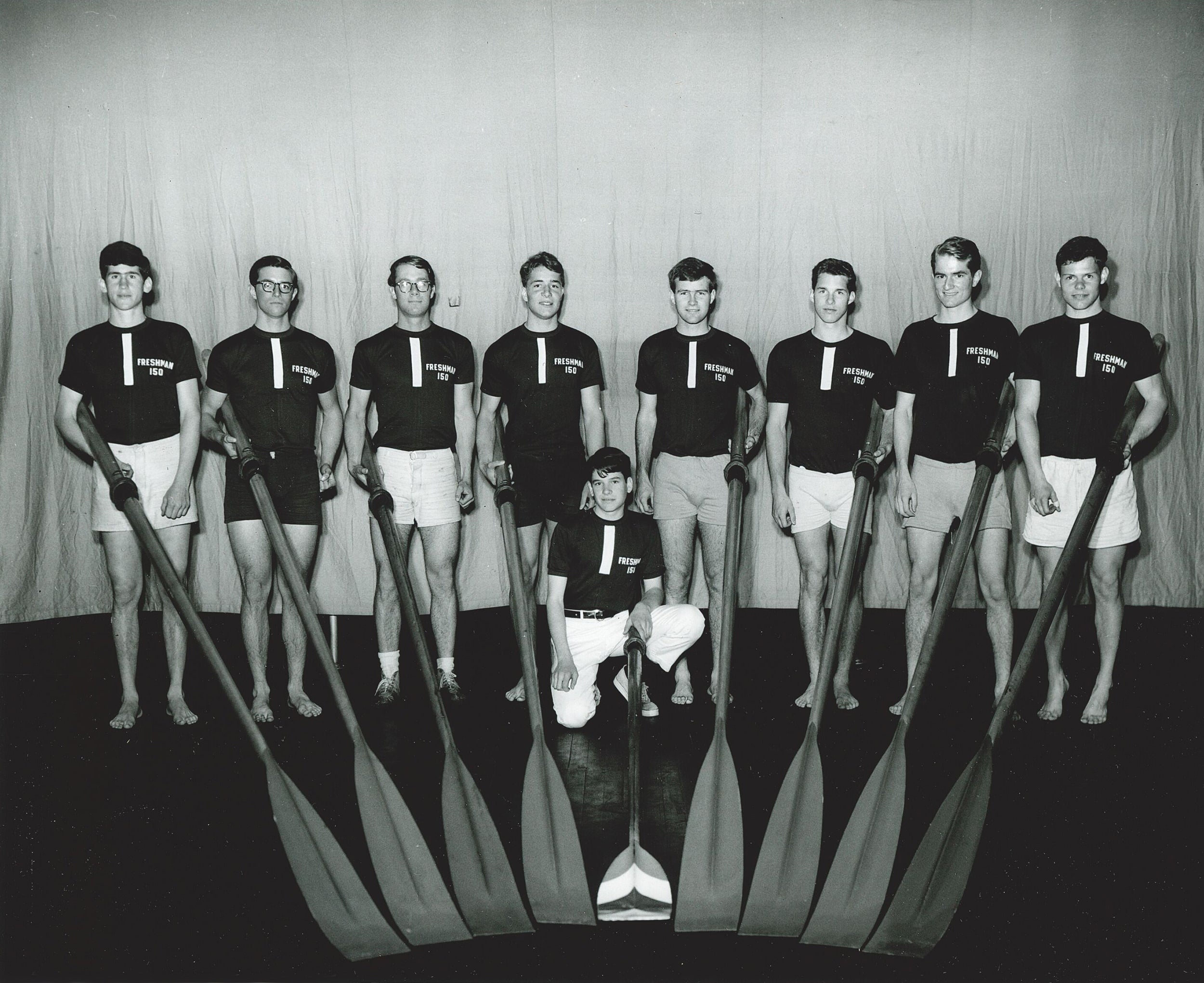

Some ’68 members didn’t make it to graduation. Carl Spaulding Thorne-Thomsen, a star crew athlete who opposed the war, left Harvard during the fall of his junior year. Disillusioned with the privilege and protection that attending a university provided, he believed it was wrong to stay in college to avoid the draft while other, less fortunate Americans were called up — a belief that eventually led him to volunteer for the draft in February of 1967. He was killed in action on Oct. 25 of that year, and was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star for heroism. In an interview with Harvard Magazine, his mother wrote later “that his decision exemplified ‘the qualities I loved most in him. He was perceptive, he hated unfairness, he was courageous, and he lived by his principles and acted on them despite personal consequences.’ ”

‘He hated unfairness, he was courageous, and he lived by his principles and acted on them despite personal consequences.’

While the 1960s are justifiably remembered for social change, they were also the beginning of a transformative artistic revolution across film, music, theater, fashion, and art. In Cambridge, Club 47, now known as Club Passim, was a center for the folk-rock movement, hosting musical luminaries Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Pete Seeger.

“You can’t really understand opposition to the Vietnam War without understanding that it was part of a much bigger counterculture,” said Peter Coonradt ’68. “There was this great upheaval and awaking of social engagement. But at the same time there was also folk music, experimental films, psychedelic drugs … this larger and deeper awareness that was spreading through this subset of people.”

A filmmaker, Coonradt is one of the driving forces behind Underground 68, an immersive counterculture experience that will be hosted by the Class of ’68 in the Leverett House Theater May 20-23. The undertaking was inspired in part by Coonradt’s connection with Ariel Smolik-Valles ’17, a student who interviewed him and other alumni for her senior thesis on campus opposition to the Vietnam War. They are currently collaborating on a film exploring the counterculture of the late ’60s through her eyes.

Although he hasn’t had much contact with his classmates over the past 50 years, working with other members of the Harvard and Radcliffe Class of 1968 on reunion committees has been a transformative experience for Coonradt.

“When I left Harvard, I never looked in the rearview mirror. I just kind of forgot about it,” he said. “I didn’t think about it until this reunion thing came along, and now, working with all these classmates on this project, I’m discovering [that was a mistake]. It’s such a wonderful bunch of people.”

“Harvard, 1968,” an exhibition featuring materials drawn from the collections of the Harvard University Archives, provides a glimpse into the events at Harvard that took place in the time just preceding and including that momentous year and is currently on view at the Pusey Library Archives.