The national anthem as lightning rod

Harvard scholars deconstruct the questions at the heart of the recent NFL protests

When President Trump called for owners of National Football League teams to fire players who take a knee during the national anthem to protest racism, the response by players and others was an even more widespread dissent before games that touched a deep cultural nerve and shook a seminal American institution.

The controversy has raised a number of questions about free speech, the intersection of sports and activism, and why “The Star-Spangled Banner” became and remains an integral part of domestic sporting events. To understand the issues in play better, the Gazette turned to Harvard scholars to discuss key aspects of them.

Free speech on the job, and on the field

Freedom of speech and expression is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment, which states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” The language makes clear that the right to free speech applies when the government is trying to suppress it. But what free speech rights do employees have on the job?

“As a general rule, the Constitution’s free speech protections don’t apply in private-sector workplaces — including the NFL — so the First Amendment generally isn’t much help here,” said Benjamin Sachs, Kestnbaum Professor of Labor and Industry at Harvard Law School and an authority on labor law.

Sachs noted that some states protect certain kinds of political speech, and that the National Labor Relations Act “prohibits employers from firing employees for speaking out about issues that impact them as employees.”

“If the players have an argument that their protest activities concern their status as employees — and I can see a possible argument in this direction — then any retaliation would be illegal,” he said. “But the players’ best form of protection, as is often the case, may come from the collective bargaining agreement between their union and the league. While players might be disciplined for doing things that are ‘detrimental to the integrity of the league,’ I would hope that free speech wouldn’t be so construed.”

More like this

The long history of sports and activism

In the United States, some of the earliest examples of activism in professional sports involved the influential athletes Joe Louis, the African-American heavyweight champion who beat German boxer Max Schmeling in a 1936 bout laden with political and social undertones, and Jackie Robinson, the first African-American to play in Major League Baseball in the modern era. These men waged their protests through their outstanding achievements in the ring and on the field.

“Through the athletic performance, personal conduct, and material support of figures like Louis or Robinson, many hoped that white supremacy and its mythology might be fatally undermined,” said Harvard’s Brandon Terry, assistant professor of African and African American Studies and Social Studies at Harvard.

Ensuing decades saw more defiant forms of sports activism.

“By the 1960s and early 1970s, black athletes — who were increasingly integrated into collegiate and professional sports — became more prominently involved in surging movements for Civil Rights and black power,” said Terry. “This era was distinguished by leading athletes’ public criticism of racial injustice, a rejection of Louis-era norms of respectability, and dramatic public gestures of solidarity with radical political movements. Think of Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics or Muhammad Ali’s explosive resistance campaign against the draft and war in Vietnam.”

But the “hostility, ostracism, and financial costs” of such rebellion “discouraged militancy in subsequent eras,” Terry said.

Today, activist athletes are often embraced by social media, and vice versa. Facebook and Twitter let players circumvent the press to reach wider audiences and coordinate demonstrations, said Terry, and athletes’ soaring salaries make them financially better able to withstand reprisals.

Social media buzzed in 2016 when Colin Kaepernick, then quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, first took a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality against African Americans and other minorities. Kaepernick’s stance simmered over time, with a few NFL players taking similar actions before games. But in last couple of weeks, Trump’s criticism helped prompt hundreds of NFL players and others to lodge their own protests.

More players have dropped to one knee for the duration of the song. Some have simply refused to show up for the anthem, including whole teams that remained in their locker rooms. Last Sunday, some players knelt with raised fists, while others joined coaches and owners on the sidelines and locked arms in solidarity.

“What is most remarkable about the Colin Kaepernick protest and its aftermath is the way that athletes — of all races — have managed to turn the loyalties generated by celebrity culture and the power of social media technologies to fight back against elites attempting to suppress their dissent and demonize them as disrespectful and ungrateful,” said Terry.

But Terry said that to change things fundamentally, protests need political clout. While he sees Kaepernick’s protest and those who support him as principled and heroic, Terry also thinks they have made the Black Lives Matter movement less popular and have shifted the conversation “away from police brutality toward questions of free speech, the prudence of athlete protest, and Kaepernick’s own employment.” Kaepernick has not been signed by any team this season.

“While the solidarity and courage evinced by athletes in the face of Trump’s assault is extraordinary and inspiring, it for now remains untethered from a comprehensive effort to support those efforts at political organization that might, in fact, confront the larger crises of police misconduct and criminal justice beyond symbolic solidarity.”

Activism in sports at Harvard and Yale

At Harvard and Yale, sports itself was originally a form of activism. In the 1840s, organized rowing was first a form of protest that let students break from “the constraints of college life,” according to John Stauffer, Harvard’s Sumner R. and Marshall S. Kates Professor of English and of African and African American Studies. “In mastering rowing or baseball, they acquired a public ‘voice’ and a degree of autonomy that had been unavailable to them in the traditional classroom.”

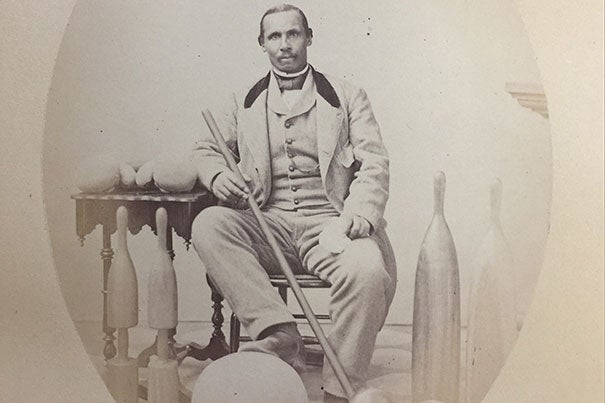

Stauffer said Harvard officials eventually sought “new voices in this new arena of sports.” A key voice belonged to Aaron Molineaux Hewlett, an accomplished athlete and trainer who was named the director and curator of a new, state-of-the-art gymnasium in 1859 by President James Walker and the Fellows of Harvard College.

The first African-American instructor at Harvard, Professor Hewlett, as he was called, taught gymnastics, boxing, wrestling, and weightlifting, “possibly to Southern slaveholders as well as antislavery Northerners,” said Stauffer, who researched the Harvard history with the help of Teddy Brokaw ’18. “His hiring on the eve of the Civil War functioned as a form of protest against slavery and white supremacy, in much the same way that NFL players today take a knee to protest racism.”

Hewlett, said Stauffer, “acquired a public voice that caught people’s attention. ‘Young America yields to the instruction of a colored man,’ declared an educational journal in 1859.” His classes were popular, Stauffer added. “In the fall of 1863 he had ‘several hundred students under him,’ according to The Christian Recorder.”

“From Hewlett’s day to today, African-Americans have used the playing field to dignify black bodies that white Americans have so often tried to destroy, to paraphrase Ta-Nehisi Coates. They teach whites the art of sport, as Hewlett did. Or they take a knee during the national anthem before displaying their art. In both cases they assert a voice that demands respect, dignity, and equality.”

The song and its history

The lyrics of the national anthem come from a poem penned on Sept. 13, 1814, by American lawyer and author Francis Scott Key during the War of 1812 as he watched British bombs rain down on a U.S. fort built to protect Baltimore from naval attack. “The Defence of Fort McHenry” provided lines to the borrowed melody of a popular British tune.

Though the song was occasionally heard at baseball games in the 1800s, it made its first big mark during a World Series game in Chicago between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs on Sept. 5, 1918. As World War I raged, Cubs officials enlisted a band to play the song (which wouldn’t become the national anthem until 1931) during the seventh inning. Players and fans stood, removed their caps, and turned to face the flag as the band struck up “The Star Spangled Banner.”

According to Sheryl Kaskowitz, the author of “God Bless America: The Surprising History of an Iconic Song,” using the anthem in a patriotic display was one way to allay concern that baseball “was a frivolous thing to be doing” while droves of American men were dying in Europe. But the main reason the tradition lapsed after the war was a simple technological issue.

“Because there was no amplification in stadiums, in order to play music like that you needed to hire a large band,” said Kaskowitz, an independent scholar who received her doctorate in music from Harvard in 2011. “Most teams couldn’t afford to do that on a regular basis, so it could only really be done on special occasions.”

It was another war gave the song new life in Major League Baseball, and another country that first adopted the practice of playing its anthem before games. Canada, which entered World War II in 1939 two years before the United States, began playing “O Canada” during professional hockey games. When the United States entered the war, it embraced playing the national anthem at sporting events, theater performances, concerts, and movies.

“After the war ended it sort of faded out from those other venues, but it stayed in sports,” said Kaskowitz.

Kaskowitz noted that the song has come to mean “many things for many people,” through the years. She said she thinks it will “always be contested, and that is part of what makes it a rich and important and democratic symbol for us.”

“A song’s meanings change and deepen over time for each of us as we accumulate different associations with it. And these competing definitions come up against each other during these public performances of the anthem at sporting events, becoming sites of protest in the struggle to define America.”