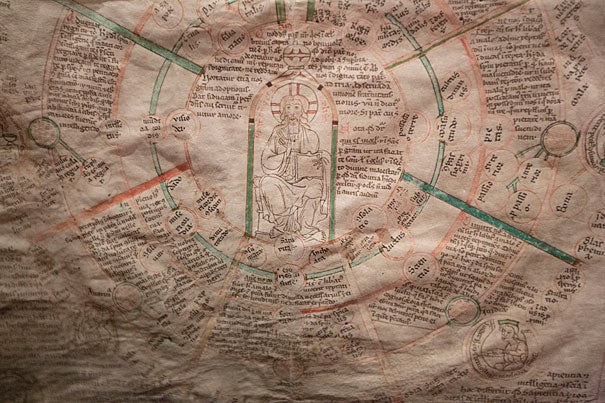

A close-up image (photo 1) shows MS Typ 584, a ca. 1200 pedagogical and devotional tool showing seven vices and seven virtues as interpreted by Hugh of St. Victor. Professor Thomas Forrest Kelly (from left, photo 2), graduate student Zoe Walls, Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts William Stoneman, and Professor Beverly Mayne Kienzle put the final touches on an exhibit of medieval scrolls now on display at Houghton Library.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Scrolls and scrolling

Digital tools key to projects in medieval studies

Scholars who work with historical objects may think of those objects as worlds apart from emerging technology, but students in two courses — one offered through the Committee on Medieval Studies and Harvard Divinity School, the other through the Program in General Education — harnessed the power of both to curate exhibits now on display.

The exhibits reflect new forms of research, teaching, and learning. One is presented in Houghton Library with an online companion exhibit in progress, and the other consists of virtual galleries built with digital collections from Harvard’s libraries and museums.

Students in “Scrolls in the Middle Ages,” a seminar course led by Morton B. Knafel Professor of Music Thomas Forrest Kelly and John H. Morison Professor of Practice in Latin and Romance Languages Beverly Mayne Kienzle, undertook a semester-long project to prepare the University’s collection of medieval scrolls for display in Houghton’s Edison and Newman Room. Their show, which features 15 scrolls, runs through Aug. 16. It is free and open to the public.

At the outset of the course, the students met with Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts William Stoneman to view the scrolls and choose one to research in-depth.

An 800- to 900-year-old-scroll is susceptible to damage if rolled and unrolled multiple times, so after their initial visits, the students relied on digitized copies to inspect writing, images, and composition.

Classics concentrator Rebecca Frankel ’15 helped prepare MS Lat 198, a small scroll that contains a secular poem written in Latin. “It’s pretty difficult to see, even when you’re standing close to it,” she said. “The fact that they were able to digitize this was really helpful because we were able to zoom in really closely and make out words that we otherwise wouldn’t be able to.”

Kienzle made clear the contributions of Houghton staff. “We can’t emphasize how much the library did in making this available so the students could do what they did.”

The digitized scrolls are available through the Harvard Library’s Page Delivery Service and will be part of the class’ forthcoming online exhibit.

“Digital is helping more people have an experience of the material culture of the Middle Ages,” Kienzle added. “It’s fantastic.”

Next-generation digital images are made using archive-quality, high-resolution photography that precisely reproduces the color of the original object on-screen. The images show close detail, such as brushstrokes and texture. They are presented as panoramic, stitched-together graphics, rather than pages, so that students can focus on particular areas but also see the larger context of a piece.

Library Technology Services is collaborating with HarvardX to enhance annotation and translation in image viewing, and to raise virtual interaction to the level of actual. The new technology is being introduced in classrooms, and will also be featured in an upcoming Harvard massive online open course, “The History of the Book,” which Kelly will co-teach.

Some members of the course were using the tools for the first time, but were able to learn from the varied technical and academic backgrounds of their classmates.

“Each of the students has found out that any single question you ask of a medieval object can expand to fill the universe because everything is connected to everything else and it turns out there’s a huge amount to know and huge amount that we have all learned,” Kelly said.

One of those questions came from Emerson Morgan, a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in historical musicology. As he prepared MS Typ II, which is longer than its display case, he deliberated over which section to show. “It raises interesting questions about stories and how they are chopped or parsed,” Morgan said. The answer helps explain why scrolling styles on the Web are sometimes revisited and revised.

Across campus, students in Professor Daniel Smail’s “Making the Middle Ages” were exploring similar connections between the past and the present. In Smail’s General Ed course, the first assignment was to search campus for items reminiscent of the medieval era and post pictures of the findings — crests from Harvard’s residential Houses, images from “Game of Thrones,” the restaurant Medieval Times — on a Tumblr blog.

From there, the students visited Harvard’s museum and library collections to examine a selection of objects from the fifth to 15th centuries. Each student selected one item to closely study its context, provenance, and purpose, and then worked with a group to fit the objects together within a common theme. Those commonalities became the basis for virtual galleries built with the Web publishing platform Omeka.

Indrani Das ’16, a concentrator in human developmental and regenerative biology, worked with her group to arrange their findings around idea dissemination and globalization. The classmates wanted to avoid organizing the exhibit by where the objects were found, so they focused on revealing recurring influences on Europe from the Middle East and Africa. The exhibit, “Tales of Transfer,” won a class competition for best gallery.

“What Professor Smail tried to get a lot of us to understand is that we’re not so different from the people that lived during the Middle Ages,” Das said. “If anything, combining the medieval history with modern technology that I’ve never used in any of my classes, let alone a history class, served to get rid of the dichotomy that we’d originally set up based on misconceptions that we grew up with.”

The same urge against dichotomies — and toward connection — was on Kelly’s mind as he reflected on the success of his course.

“I think this same sort of thing can be done at Harvard in many, many other ways just by changing the nouns: You just change the word ‘scroll’ to — I don’t know what — ‘reliquary’ or ‘leather bookbinding’ or ‘Native American headgear.’ … This has for me been a really interesting experiment in how to use tangible objects at Harvard to relate people to each other and to relate those collections to the intellectual and cultural history not just here, but throughout the world.”