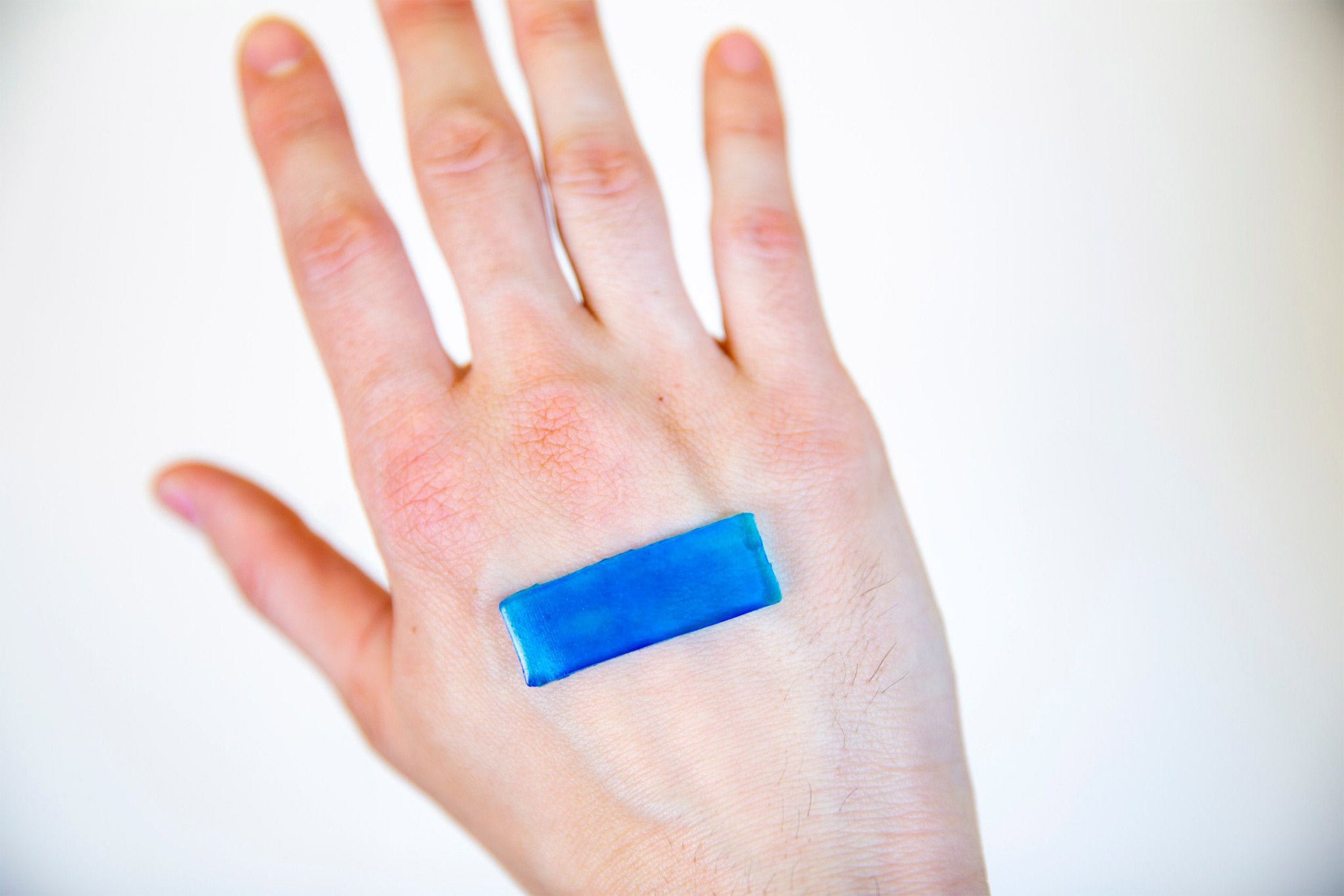

The active adhesive dressing contracts when it heats up to body temperature, allowing it to accelerate the healing of open wounds on the skin.

Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

Using body heat to speed healing

Bioinspired wound dressing contracts in response to warmth

Cuts, scrapes, blisters, burns, splinters, and punctures — there are a number of ways our skin can be broken. Most treatments for skin wounds involve simply covering them with a barrier (usually an adhesive gauze bandage) to keep them moist, limit pain, and reduce exposure to infectious microbes, but they do not actively assist in the healing process.

More sophisticated wound dressings that can monitor aspects of healing such as pH and temperature and deliver therapies to a wound site have been developed in recent years, but they are complex to manufacture, expensive, and difficult to customize, limiting their potential for widespread use.

Now, a new, scalable approach to speeding up wound healing has been developed based on heat-responsive hydrogels that are mechanically active, stretchy, tough, highly adhesive, and antimicrobial: active adhesive dressings (AADs). Created by researchers at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, the Harvard John A. Paulson School for Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and McGill University, AADs can close wounds significantly faster than other methods and prevent bacterial growth without the need for any additional apparatus or stimuli. The research is reported in Science Advances.

“This technology has the potential to be used not only for skin injuries, but also for chronic wounds like diabetic ulcers and pressure sores, for drug delivery, and as components of soft robotics-based therapies,” said corresponding author David Mooney, a founding core faculty member of the Wyss Institute and the Robert P. Pinkas Family Professor of Bioengineering at SEAS.

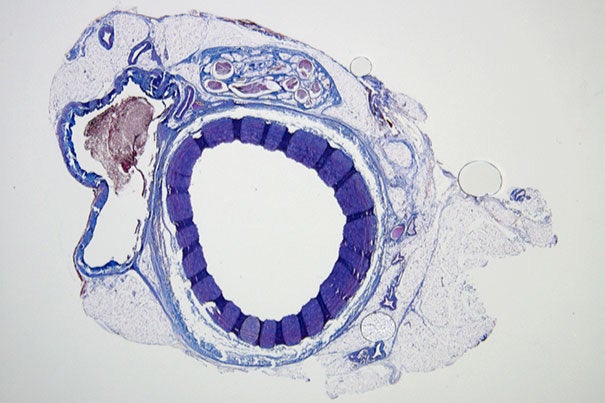

AADs take their inspiration from developing embryos, whose skin is able to heal itself completely, without forming scar tissue. To achieve this, the embryonic skin cells around a wound produce fibers made of the protein actin that contract to draw the wound edges together, like a drawstring bag being pulled closed. Skin cells lose this ability once a fetus develops past a certain age, and any injuries that occur after that point cause inflammation and scarring during the healing process.

To mimic the contractile forces that pull embryonic skin wounds closed, the researchers extended the design of previously developed tough, adhesive hydrogels by adding a thermoresponsive polymer known as PNIPAm, which both repels water and shrinks at around 90 degrees Fahrenheit. The resulting hybrid hydrogel begins to contract when exposed to body heat, and transmits the force of the contracting PNIPAm component to the underlying tissue viastrong bonds between the alginate hydrogel and the tissue. In addition, silver nanoparticles are embedded in the AAD to provide antimicrobial protection.

“This technology has the potential to be used not only for skin injuries, but also for chronic wounds like diabetic ulcers and pressure sores, for drug delivery, and as components of soft robotics-based therapies.”

David Mooney

“The AAD bonded to pig skin with over 10 times the adhesive force of a Band-Aid and prevented bacteria from growing, so this technology is already significantly better than most commonly used wound protection products, even before considering its wound-closing properties,” said Benjamin Freedman, a Graduate School of Arts and Sciences’ postdoctoral fellow in the Mooney lab who is leading the project.

To test how well their AAD closed wounds, the researchers tested it on patches of mouse skin and found that it reduced the size of the wound area by about 45 percent compared to almost no change in area in the untreated samples, and closed wounds faster than treatments including microgels, chitosan, gelatin, and other types of hydrogels. The AAD also did not cause inflammation or immune responses, indicating that it is safe for use in and on living tissues.

Furthermore, the researchers were able to adjust the amount of wound closure performed by the AAD by adding different amounts of acrylamide monomers during the manufacturing process. “This property could be useful when applying the adhesive to wounds on a joint like the elbow, which moves around a lot and would probably benefit from a looser bond, compared to a more static area of the body like the shin,” said co-first author Jianyu Li, a former postdoctoral fellow at the Wyss Institute who is now an assistant professor at McGill University.

The team also created a computer simulation of AAD-assisted wound closure, which predicted that AAD could cause human skin to contract at a rate comparable to that of mouse skin, indicating that it has a higher likelihood of displaying a clinical benefit in human patients.

“We are continuing this research with studies to learn more about how the mechanical cues exerted by AAD impact the biological process of wound healing, and how AAD performs across a range of different temperatures, as body temperature can vary at different locations,” said Freedman. “We hope to pursue additional preclinical studies to demonstrate AAD’s potential as a medical product, and then work toward commercialization.”

Additional authors of the paper include co-first author Serena Blacklow, a former member of the Mooney lab who is now a graduate student at the University of California, San Francisco; Mahdi Zeidi, a graduate student at University of Toronto; and Chao Chen, a former graduate student in SEAS who is now a postdoc at UMass Amherst.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and the Harvard University Materials Research Science and Engineering Center.