Former Radcliffe fellow Julie Orringer wrote a novel about Varian Fry ’30, who helped save Jewish artists, writers, and musicians from the Holocaust.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

The ‘American Schindler’

Former Radcliffe fellow’s new novel focuses on Harvard grad who saved Jewish artists during World War II

Author Julie Orringer’s “The Flight Portfolio” is rooted in history. The novel tells the story of Harvard graduate Varian Fry ’30, a journalist and editor who was sometimes referred to as the “American Schindler.” While working for the Emergency Rescue Committee in France during World War II, Fry helped save Jewish members of Europe’s cultural elite, including artists, writers, and musicians, from Nazi concentration camps. Orringer worked on the book when she was the Lisa Goldberg Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in 2013–14. The Gazette spoke with her about the book and how her time on campus helped her shape it.

Q&A

Julie Orringer

GAZETTE: A key theme in the book involves this question of how you can value one person’s life over another’s. The characters struggle with their work, which involves choosing whom to save during the Holocaust. How did you decide to incorporate this into the story?

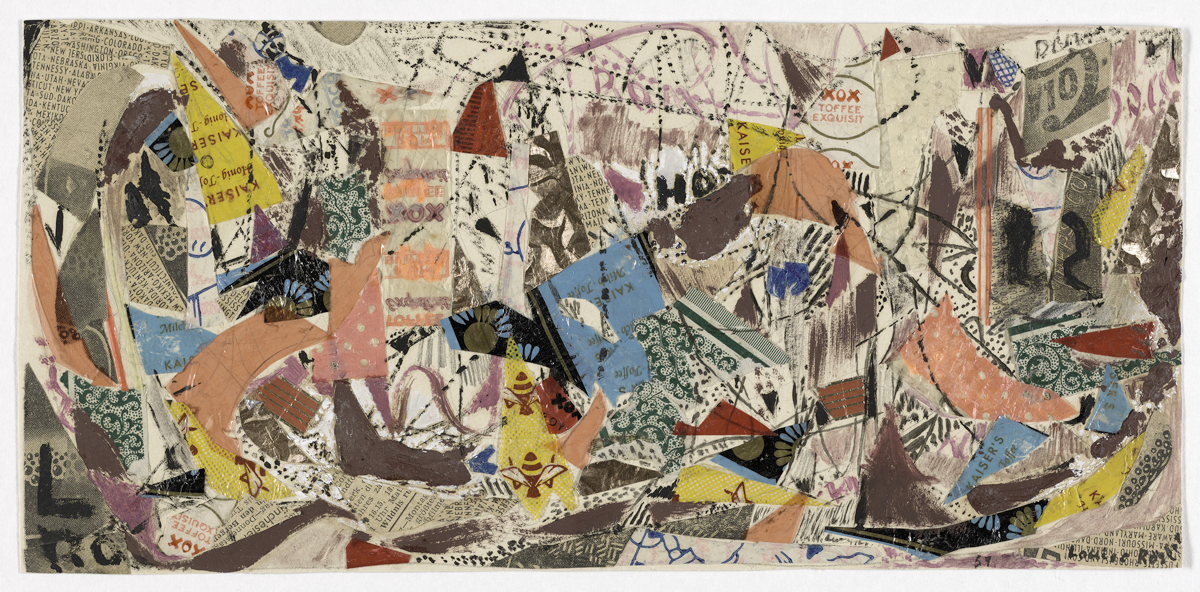

ORRINGER: That was the element of Varian Fry’s experience that I was most fascinated by as a novelist. How does a person make those impossible moral decisions? Given an unlimited number of potential clients and limited time and funds, how do you prioritize? The mandate of Fry’s organization was to save Europe’s most brilliant writers and artists — but how to determine artistic merit among hundreds of refugees, all of them desperate for help?

The question often led Fry and his associates to desperate measures. Sometimes they would send potential clients down to [Marseille’s] Vieux Port and ask them to make a few sketches. Then Fry’s associate, Miriam Davenport, trained in art history at the Sorbonne, would look at these sketches and determine whether the artist had talent — whether, in effect, they deserved to be helped, according to the committee’s mandate. What would it have been like to be that artist, forced to produce work that might mean the difference between life or death? And what would it be like to be the person who had to look at those hasty sketches and determine whether their creator should receive life-saving help? Was it right to help certain artists and not others? Was it right to privilege artists at all? That felt to me like an unanswerable question, and I think as novelists we often look for questions like that — the kind that can be argued infinitely from either side.

GAZETTE: Do you find it harder to blend fact and fiction in a novel like “The Flight Portfolio,” or to create a pure work of fiction as you’ve done in your short story collection “How to Breathe Underwater”?

ORRINGER: Even my short stories blended fiction and personal history. And while I know there’s a difference between writing about private lives and public ones, every public life is just a single person’s experience; the history that surrounds it is comprised of stories told by human beings too. With this book it was extremely important for me to be faithful to the known historical record. But it also struck me that there were so many apertures in that record, so much that couldn’t be known, or that couldn’t have been recorded at the time. A novelist extrapolates from history. It’s what we’ve always done. It’s what Shakespeare did in “Henry V,” and Tolstoy in “War and Peace,” and Colm Tóibin in “The Master,” and Hilary Mantel in “Wolf Hall” and “Bring Up the Bodies.”

Fiction gives us access to others’ minds in a way that no other art form does. As we read, we take those minds into our own; in a sense, we become them. The act of involving oneself in a work of fiction involves creative extrapolation. The form requires that work from us whether our subjects are entirely invented or not. I’m fascinated by stories wherever I encounter them, and when I learned about Varian Fry’s work in the course of researching my last book, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Here was this book editor and journalist who’d gotten out from behind his desk and gone to occupied France to save writers and artists’ lives; his work ended up shaping the second half of the 20th century. And I’d never heard his name. I wanted his story to be told, even though I knew there would be challenges involved in capturing and fictionalizing the life of a historical figure.

GAZETTE: You were at Harvard on a Radcliffe fellowship. Can you talk about the importance of that program and how the exchange that the Institute promotes among the different fellows from so many varied fields influenced your work?

ORRINGER: Being at Radcliffe was transformative for this book. While I was there, my colleague Lewis Hyde put together a group of writers — people who were producing work in all different genres — to meet every month to talk about how our projects were progressing and the difficulties we were having. The group was fertile ground for new ideas, but we challenged each other too. It was especially exciting to hear about Lewis’s book, “A Primer for Forgetting,” which will be published this June by FSG. We were both thinking about history — what we remember, what we choose to forget, and what we bury because it’s too problematic. Those conversations with Lewis affected my thinking about the issues that lie at the heart of “The Flight Portfolio.”

There was also the incredible gift of getting to know the work of scholars in wildly diverse fields. One fellow was studying the physics of toys; another was an astrophysicist studying the formation of massive galaxies; another studied the shape of bird skulls; and another, the importance of water to public health in India. Among us all, there was an incredible sense of fruitful exploration. We had the freedom to push further into a deep understanding of our subjects. That’s one of the things the Radcliffe Institute does best: It allows for room to grow. And as we presented our work to each other and heard about each other’s projects, there was a sense of self-consciousness falling away, a developing sense of play and exploration, a sense of listening, of interest across genres and across fields, one that seemed to introduce a creative energy into everyone’s work.

“What would it be like to be the person who had to look at those hasty sketches and determine whether their creator should receive life-saving help?”

GAZETTE: You worked with undergraduate researchers during your time at Radcliffe. Can you talk a little bit about what that process was like and how it helped shape your work?

ORRINGER: At the beginning of the year, when I learned it was possible for fellows to work with undergraduate research assistants, I thought how fantastic that would be for the other fellows — for the scientists and historians and literary scholars. I couldn’t imagine how a novelist might work with a research fellow. But [Fellowship Program Associate Dean] Judith Vichniac … encouraged me to expand my thinking on the subject. At the very least, wouldn’t it be interesting to talk with a couple of young writers about how one goes about conducting historical research?

I ended up working with two marvelous fellows, Victoria Baena and Anna Hagen, the editor and the fiction editor of The Harvard Advocate. Both are fiction writers themselves, so they already understood a lot of what went into the process of engaging history in a novel. The research they conducted was essential to my project, and continued to help for years afterward. They created a timeline of events in Varian Fry’s 13 months in Marseille, and assembled mini-biographies of the writers and artists he saved. They combed through his student file at Harvard, a rich trove that contained, among other things, his Harvard application, letters from his professors and the dean and his parents, all his grade transcripts, and a record of every place he lived in Cambridge. Anna and Victoria spent a lot of time capturing important facts, transcribing letters, and cataloguing documents online so they would be available to me even when I left Harvard.

I also discovered how helpful it was to talk to these two brilliant young women about decisions I was making for the novel. In the process, I found myself questioning my own assumptions and pushing toward greater risk. That academic relationship could not have existed anywhere but at Radcliffe. In the end, I had Judy Vichniac to thank for the incredible richness of that experience — for the privilege of working with those powerful creative minds, and for the chance to enjoy a daily practice of collaborative thinking, an all-too-rare experience for novelists.