“Nomad Suitcase,” 2004. © Nam June Paik Estate

Video by Justin Saglio/Harvard Staff

He was a musician by training whose conceptual art frequently blended the aural and the visual into the quirky and quixotic. Credited with coining the term “electronic superhighway,” he was famous for mixing sculpture and performance with a relatively new invention called television, which in time would define his creative output.

Seoul-born Nam June Paik, known as the father of video art, was also a relative of Ken Hakuta, M.B.A. ’77, who has gifted a number of his uncle’s pieces to the Harvard Art Museums in recent years. Those works are the focus of “Nam June Paik: Screen Play,” on view through Aug. 5.

“Paik was a really important player in artistic developments over the 20th century,” said Mary Schneider Enriquez, Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, who helped curate the show. The artist’s effort to engage viewers with his work was “revolutionary,” Enriquez added, as was his “electronic way of thinking about this interaction.”

Born in 1932, Paik was a budding classical pianist when the Korean War forced him to flee with his family to Hong Kong and eventually to Japan, where he studied music at the University of Tokyo. Later, as a student in West Germany in the late 1950s, he met artist Joseph Beuys, avant-garde musician John Cage, and members of what would eventually become Fluxus, a 1960s movement that rejected the commercial art market in favor of art for the masses.

Cage is perhaps best known for “4’33,” in which a pianist sits for four minutes and thirty-three seconds at a piano without playing a note. Paik’s reaction to the composer’s work was similar to that of many experimental artists of the era.

“Cage really was that epiphany for a lot of artists during this period and I think he just really expanded Paik’s idea of what music and art could be,” said Marina Isgro, Nam June Paik Research Fellow and curator of the new show.

“White TV,” 2005.

© Nam June Paik Estate; video by Justin Saglio/Harvard Staff

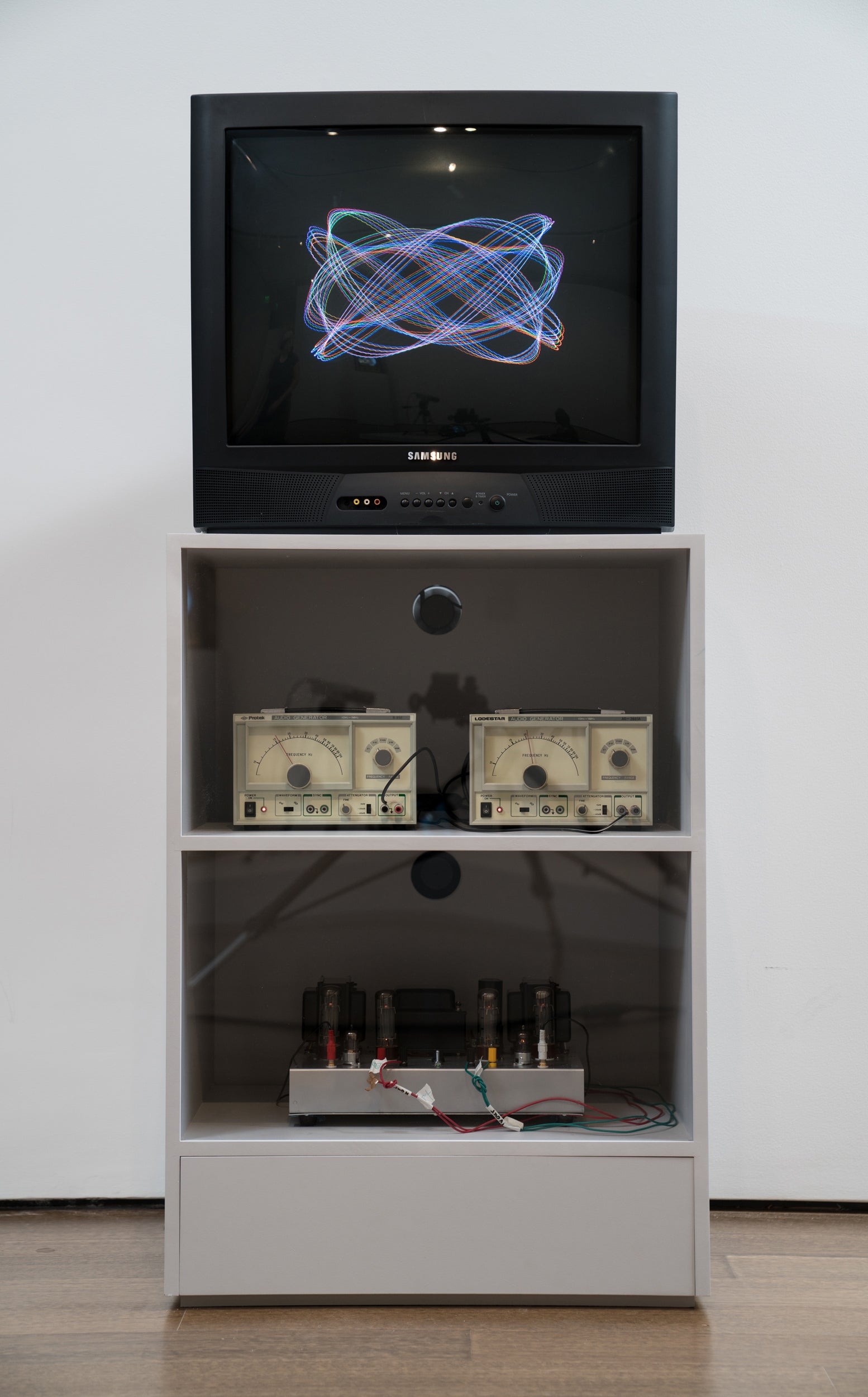

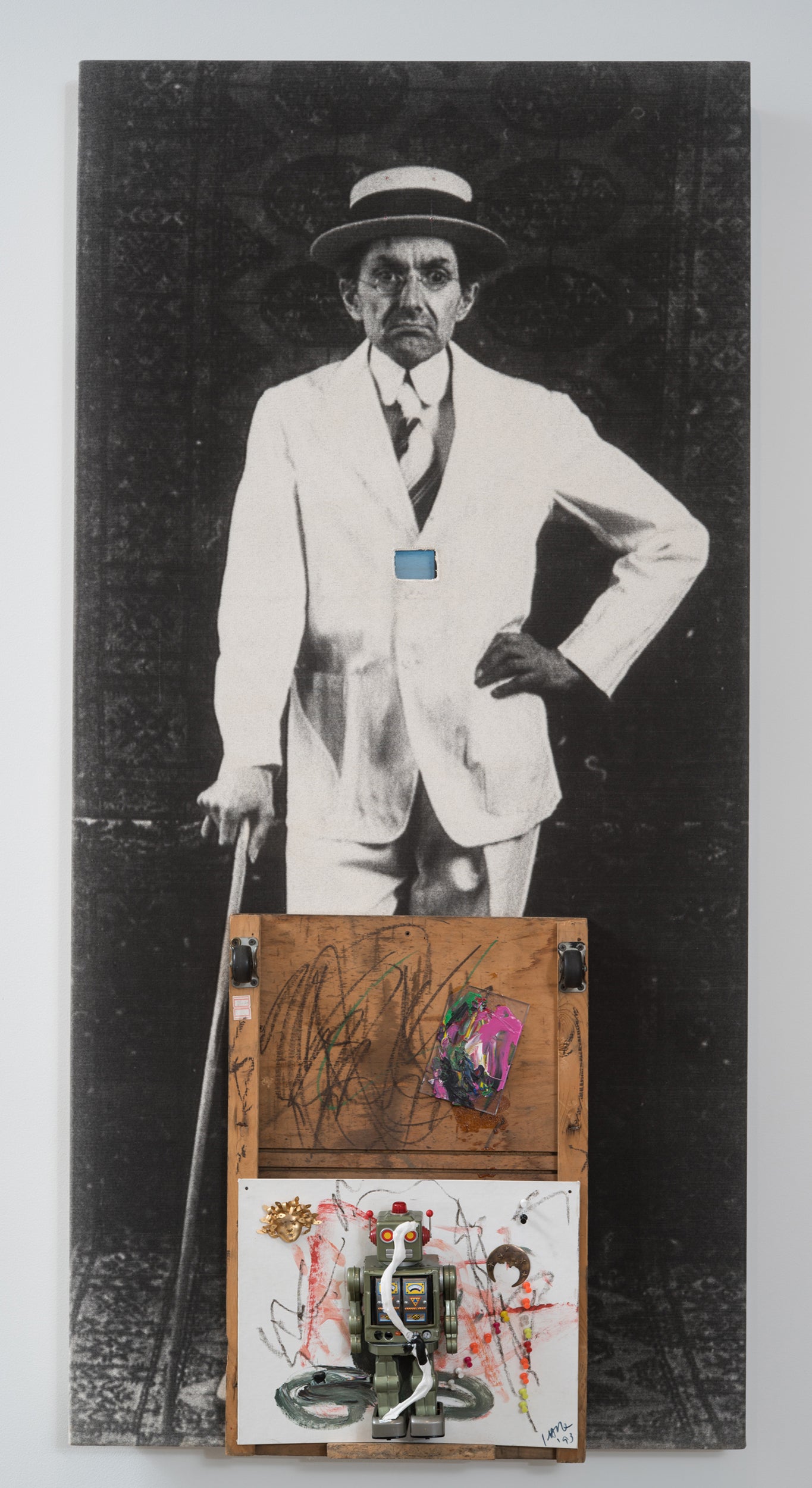

“TV Crown,” 1965; Untitled, 1993–95.

© Nam June Paik Estate. Photo: Karen Philippi; © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Inspired by a new sense of artistic possibility, Paik developed “TV Crown” in 1965, one of the first pieces to greet visitors as they enter the third-floor gallery at Harvard Art Museums. The installation consists of a TV hooked to two audio-wave generators and an amplifier. Paik rewired the TV so that instead of displaying a broadcast, “it’s showing you these abstract patterns that are actually soundwaves visualized,” said Isgro.

Paik included knobs on the sculpture that viewers could turn to change the picture on the screen, a feature that has since been covered in Plexiglas in order to preserve the piece. At the time, the interactive quality of the work set it apart, as did its whimsy, said Enriquez.

“This was done way before we even knew we could do something like this … It was a moment of something exploratory, experimental, and fun,” she said, noting Paik’s “sense of joy and playfulness,” and his urge to “tinker and play with trying things out in a way that actually was profoundly important.”

That imaginative spark animates “TV Buddha.” A bronze Buddha statue sits across from a small television set, its image captured by a closed-circuit camera connected to the TV. The Buddha appears to be watching himself; the visitor who wanders behind the sculpture will catch his or her own image on the screen.

“It’s kind of reflecting on this idea of television as being able to provide us with a live and immediate experience, something that film couldn’t do … but it’s also an image of the Buddha just looking at its own face for all eternity,” said Isgro. “And I think that really speaks to the sense of narcissism that technology can bring about.”

“TV Buddha,” 2004.

© Nam June Paik Estate. Photo: Karen Philippi; © President and Fellows of Harvard College

“Cello Memory,” 2002.

© Nam June Paik Estate. Photo: Karen Philippi; © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Mary Schneider Enriquez (left) and Marina Isgro curated the show.

Photo by Jenna Lang

In addition to gifting numerous works to Harvard, Hakuta established the two-year fellowship held by Isgro, whose central task in researching and organizing the current show was to demonstrate Paik’s range. The exhibit features large-scale video works as well as several prints, including an untitled screen print meant to depict static on a television screen. Paik’s playful side comes through in “Primeval Piano,” a sculpture of wood and nails resembling a xylophone, and in the oil-paint-inscribed model trains of “Fluxus Express.”

Collaboration is another theme running through the exhibit. The installation “Cello Memory” consists of a stringless cello connected to two monitors. The work is dedicated to cellist Charlotte Moorman, a frequent Paik collaborator who took part in his “TV Bra for Living Sculpture,” a 1969 performance piece in which Moorman played her instrument wearing a plastic bra adorned with two small TV sets.

In addition to shining a light on Paik’s work, Enriquez hopes the show will offer visitors a sense of the range of Harvard’s holdings. “It’s a very exciting venture … a number of people in the Boston area have heard we are doing this and their reaction has been, ‘Really, Harvard has Paik?’”

Harvard Art Museums will feature a series of gallery talks in connection with the exhibit.