Drawing wisdom from drawings

Harvard seminars lead to evocative gallery show at the Harvard Art Museums

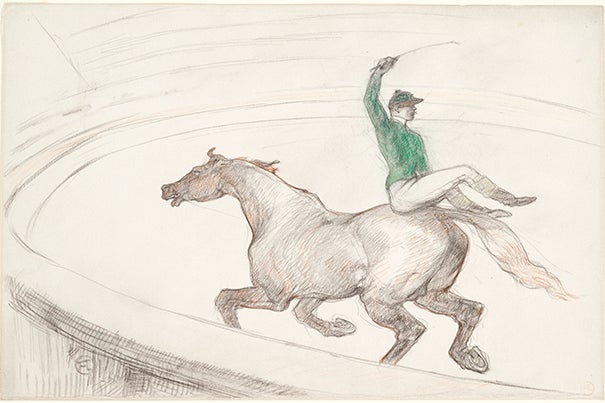

We think of drawing as a simple process, but a new exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums illustrates how, in the hands of masters, it can be anything but.

The show offers up a diverse sampling of the museums’ vast and rich collection of drawings, and also highlights the creativity of Harvard’s classrooms.

In a third-floor teaching gallery, vivid pictures by Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh hang near those by artists who, though lesser-known, produced works no less evocative, such as a lush pastel by French portraitist Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, and a haunting black-chalk image by French realist Gustave Courbet. The exhibition features 60 pieces, including 54 drawings and three sketchbooks, and is largely the construction of two Harvard seminars.

Ewa Lajer-Burcharth had long wanted to collaborate with students on a museum exhibition. The result took years of planning, hours of vigorous debate, and much careful research and conservation that yielded fresh discoveries.

“Drawing: The Invention of a Modern Medium” explores the development of the art through the 18th and 19th centuries, from a largely preparatory exercise for painting and sculpture to an autonomous form of expression and creativity fueled by myriad influences, including politics, culture, artist intent, and popular taste.

On view through May 17, the show breaks from the traditional linear exhibition format, inviting viewers instead to explore the artworks through the lens of three main themes — medium, discourse, and object — and several subcategories within those themes, such as line, color, touch, surface and reproduction.

“This is a little more dynamic, a little more challenging, but also a little more user-friendly way of getting to people to think, through drawing,” said Lajer-Burcharth, the William Dorr Boardman Professor of Fine Arts. “[It’s] about how an actual physical object hanging on a wall in a constellation of other objects makes you think about art, about ideas … and make new connections.”

Engaging students directly with vast numbers of drawings was a critical part of the learning process and development of the show, said Lajer-Burcharth, who co-taught the seminars with Elizabeth Rudy, the Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Associate Curator of Prints. College senior Diana Ingerman, who took part in the undergraduate seminar in the fall of 2015, agreed.

“Anybody who knows a little bit about studying art and material cultures will tell you there’s no experience that is more important to writing and researching a work of art than that of being face-to-face with it,” said Ingerman, who examined many of the drawings alongside her classmates in the museums’ study centers, where the two courses were taught and where works from the museums are available for close inspection.

“Lively and heated debates” ensued as students in each seminar narrowed down the original selection of drawings and objects from 115 to the 60 now on display, said Rudy. As their final project, graduate students contributed essays for the show’s forthcoming catalog. The College students wrote the wall texts for the exhibition, which are included in an accompanying digital tool.

“We had a lot of decision-making power in the curatorial realm, which was very exciting. It was really empowering and also gave all of us a lot of ownership over the work that we were doing,” said Ingerman, who researched the ways that surface can be interpreted through drawing. In her description of Degas’ pastel “After the Bath, Woman with Towel,” Ingerman explains how the artist drew inspiration from the Venetian fresco technique of layering one color atop another. “In applying successive layers of opaque color and allowing spaces for earlier layers to show through,” her text notes, Degas “invented a grid-like weaving of colored marks, echoing the texture of the wove paper below.”

Work on the exhibition led to some surprising finds. While researching the design for a mausoleum plaque commemorating Benjamin Franklin, Harmon Siegel, a Ph.D. candidate in the history of art, realized that the drawing, originally attributed to another hand, was actually the product of Honoré Sébastien Royllet. Conservators scrutinized another work in preparation for the show and found it was done in a different medium than originally believed.

“This kind of a project is extremely exciting and absolutely critical to what our mission is as a museum, working with students but also showcasing the very latest and up-to-date research on our collection,” said Rudy. “Every project in the museum allows us to take a closer, more careful look at our collection,” she added, “but how much more exciting to do that with our students.”

As part of the course, students interacted with Harvard’s in-house experts as well as with scholars from elsewhere. Harvard curators and conservators worked closely with the students in each seminar, and the students visited the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where they met with the drawings curator to find out “what it takes to organize an exhibition,” Lajer-Burcharth said.

What it takes, Ingerman found, was a lot of hard work. But the reward was well worth the effort for the history of art and architecture concentrator, who called the seminar “one of my favorite courses” at Harvard.

“To get real, hands-on work in a classroom setting is something that I am grateful for,” she said, and “really invaluable.”

For more information on talks related to the exhibit, click here.