Radcliffe exhibit turns touch into sight

Blind, sighted, and hearing-impaired find common ground in ‘Calm. Smoke rises vertically’

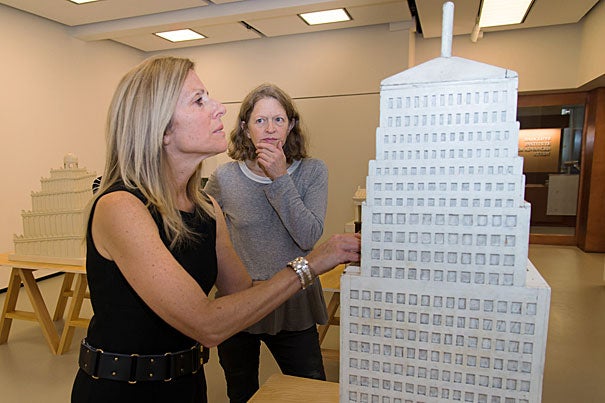

“Calm. Smoke rises vertically” at Radcliffe Institute’s Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery gives visitors permission to use the sense least indulged at most art exhibits: touch.

By combining a tactile theme with art, architecture, and innovation, artist Wendy Jacob RI ’05 has created an exhibit designed for the sighted, sightless, and hearing-impaired.

For the hearing and hearing-impaired, “hotspots” on the walls provide live-stream NOAA broadcasts and emit vibrations when they are touched; another hotspot allows visitors to experience the ever-changing climate outside.

Within this single room at the institute’s Byerly Hall gallery, the artist has opened the door to inclusivity through social connections and shared experiences. It is here that “touching can be synonymous with seeing.”

The best advice for visitors: keep your gloves at home.

Jacob, who was the Mary I. Bunting Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute in 2004–2005, spoke about her work and what she hoped to accomplish in “Calm. Smoke rises vertically.”

GAZETTE: Why did you choose the title “Calm. Smoke rises vertically” and what does it represent in light of the exhibit?

JACOB: The title comes from the Beaufort scale, an empirical measure that relates wind speed to observed conditions at sea or on land. I chose it because it describes something that is not visible — the wind — in poetic language. “Smoke rises vertically” describes winds blowing at less than 1 knot, or dead calm. One of the first [scale] models you encounter when you enter the gallery is a clapboard house with a chimney square in the center of its roof. If there were a fire in its fireplace, the smoke would be rising vertically.

GAZETTE: Why the interest in providing an exhibit for those with limited or no sight? How do you think the sighted person will respond to the exhibit vs. those without? Is there a message you want to send to the general public?

JACOB: A teacher at the Ohio State School for the Blind described being able to “see” when he wore his leather-soled shoes. I like the idea that seeing is bigger than vision, and that if you are attentive, information can be absorbed through your fingertips and toes. I didn’t make the work for a specific audience; rather, I learned from the experiences of those with limited or no sight, and created the work around the premise that touching can be synonymous with seeing. I am interested in challenging what it means to “see.”

GAZETTE: What inspired you to include scale models from the Work Progress Administration (WPA) project in your exhibit, using them for their original purpose — as tactile pieces?

JACOB: The WPA models were built to be touched. It would be too bad to take them out of circulation as touchable objects, and reduce them to historical artifacts.

GAZETTE: What is the story behind the models? Where were they stored and what kind of condition were they in when you got them? How much time did you invest in preparing (or repairing) these delicate buildings?

JACOB: I borrowed models from the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, and the Ohio State School for the Blind in Columbus, both of which commissioned models in the 1930s. The models at Perkins are housed in the school’s Tactile Museum, along with a taxidermied bear, model of a rock ship, and other treasures. Perkins has a volunteer who cares for the objects, and repaints and repairs them as need be.

The models in Columbus are housed in an old bowling alley in the basement of the school. Several times in their 80-year-old history they were at risk of being thrown away, but each time a vigilant teacher or principal intervened. We took just the most travel-worthy ones, but even they needed quite a bit of attention. For the two weeks prior to the opening a team of Harvard students and I cleaned the models with Q-tips, glued loose boards and columns back in place, and rehung miniature doors in their miniature doorframes.

GAZETTE: You have scale models that date back to the mid-1930s and you have walls that talk. That’s a remarkable combination, especially using the NOAA weather broadcast live stream within the walls. How did you make that happen and why that particular broadcast?

JACOB: I like your observation about the use of different time scales. The buildings are 80 years old, but the weather is now. The weather is the context for the building that houses the gallery and installation, and, by bringing it in via mics and streaming radio, the weather also becomes the context for the space of the gallery and the models within it. I chose the NOAA weather report because it is constantly streaming live updates, and also because it delivers information without hype or drama. It also comes with a staticky buzz that makes me think of old-time radio.

The streaming radio and other sounds are played through giant transducers attached to studs inside the walls, effectively turning the walls into surfaces for listening.

GAZETTE: Why did you include a wall that allows you to hear what is happening outside the gallery as well?

JACOB: We have a mic outside the gallery picking up the sounds of whatever is going on. It is another way of bringing the outside in, and creating a parallel atmosphere for the models. If it’s quiet outside you won’t hear a thing. If a truck rumbles by or it’s raining, you can feel it as well as hear it. If we are lucky enough to have a freak winter thunderstorm, you would really be able to feel it, especially if you were to lean against the wall.

GAZETTE: As a writer without sight and with limited hearing, holding my hands against the walls and feeling the vibration produced by sound was quite engaging. Which leads me to the question: Do you think this concept will make its way into mainstream architecture? The “walls of the future” that would use human touch to provide a particular service?

JACOB: That’s a great idea! When I was at the Ohio State School for the Blind, Celia Peirano, the third-grade teacher, told me that her kids often complained that they didn’t know what was going on outside because the classroom windows were so high that the sound of the weather didn’t make its way in. What we have lost in energy-conserving architecture is a connection with the outdoors. I like the idea that the “walls of the future” might be able to provide this.

GAZETTE: When did you first become interested in art and design?

JACOB: It goes back to as early as I can remember. My grandfather, aunt, and a great-uncle were all artists, so my family encouraged me.

GAZETTE: What are your plans for your next project?

JACOB: My process is very open-ended. Working with the Braille Press here in Boston has inspired me to think about the possibility of creating objects that work in different languages simultaneously.

“Calm. Smoke rises vertically” was created in collaboration with the Perkins School for the Blind and the Ohio State School for the Blind. It is on display through Jan. 14, 2017, at the Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery, Byerly Hall, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, 8 Garden St., Cambridge. The gallery is free and open to the public. Its hours are noon to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday.

Writer Nina Livingstone, who is blind and hearing-impaired, covers a wide range of topics in her work, which includes columns, film, and public speaking. To learn more, visit her website or contact her at nina@destinationmirth.com.