Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, assistant professor of the history of art and architecture and African and African-American studies, guest edited the magazine Aperture, producing an issue called “Vision & Justice,” the first on African-Americans, race, and photography for the magazine.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Curating a visual record

Sarah Lewis guest edits Aperture magazine as she readies a new class on African-Americans, race, and photography

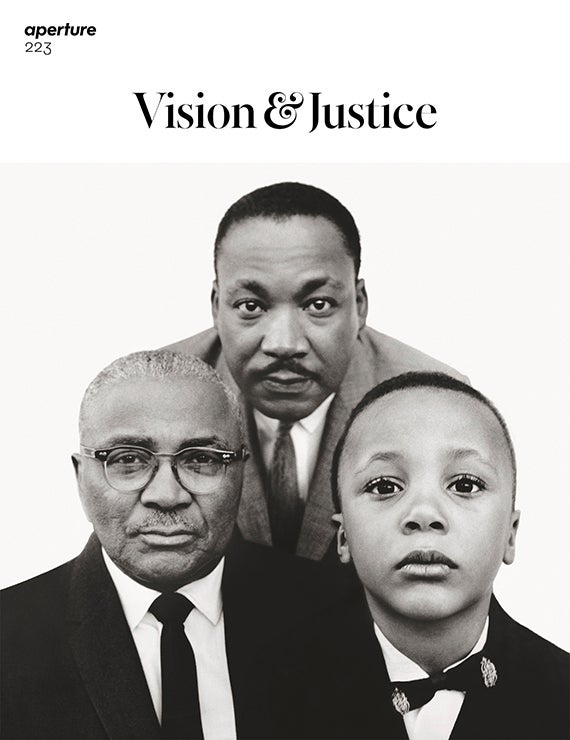

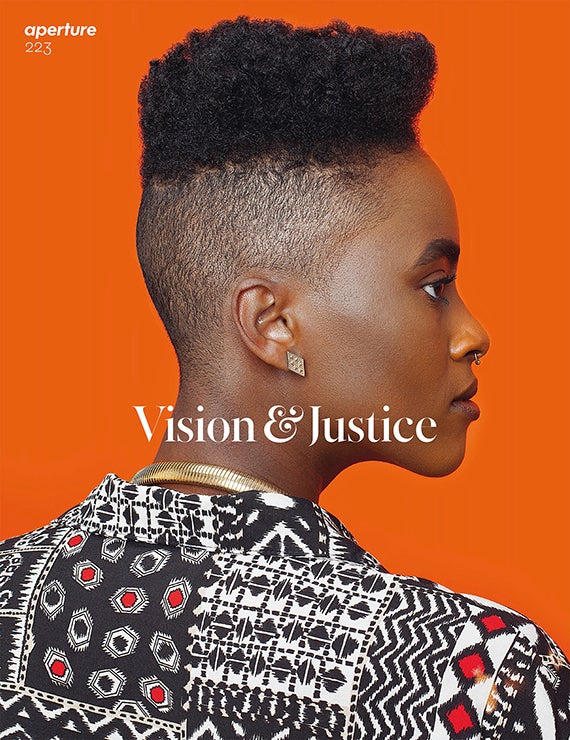

The new issue of the photography magazine Aperture, which just hit newsstands, is one of the largest in its history. The publisher even deemed the issue, titled “Vision & Justice,” worthy of two covers: the famous 1963 Richard Avedon photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. with his father and son, and an Afropunk fashion portrait shot by Awol Erizku that appeared in Vogue in 2014.

Credit Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, assistant professor of history of art and architecture and of African and African-American studies, as the creative force behind the powerful project. As guest editor, she calls the 152-page magazine on race, photography, and history “significant.” It is the first issue on African-Americans, race, and photography for the magazine.

“Photography plays a central role in the relationship of race, citizenship, and justice in this country. Yet recognizing the interventions of works of and by African-Americans to the larger history of photography has been a far more recent development,” Lewis said. “As a landmark photography foundation, Aperture recognized this and wanted to address it directly. The result of the issue is a commitment to more sustained engagement with the fuller range of images that shape our world.”

Lewis assembled a veritable who’s who of academic and artistic luminaries for the issue, including Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, who penned the cornerstone piece about the much-photographed Frederick Douglass and his exacting use of the medium to effect change; Robin Kelsey, Shirley Carter Burden Professor of Photography and chair of the Department of History of Art and Architecture, who contributed reflections on Carrie Mae Weems’ “The Kitchen Table Series”; and an essay by Khalil Gibran Muhammad, professor of history, race, and public policy at Harvard Kennedy School and Suzanne Young Murray Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, on contemporary urban portraitist Jamel Shabazz. Other Aperture voices include Leigh Raiford, associate professor of African-American studies at the University of California, Berkeley; and Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Associate Curator Thomas J. Lax.

“My aim was to create a collection of artists, writers, curators, poets, and scholars that honored the gravitas and urgency of this underexplored relationship of vision and justice,” said Lewis, who celebrated the launch of “Vision & Justice,” at an event earlier this month at the Ford Foundation in New York City that included Weems, Deborah Willis, Sarah Jones, and Chelsea Clinton.

Lewis ’01 joined the Harvard faculty this year, and has a larger plan for “Vision & Justice.” Beyond the magazine, she will teach a class of the same name this fall with related works on display at the Harvard Art Museums, where students and museum visitors can study the works.

“Visual literacy is increasingly urgent today. Engaged global citizenship requires grappling with pictures. We’re now able to witness injustices firsthand on a massive scale that would have been unimaginable decades ago, because of technology. We have to constantly read images with both our retinal mind and our reading mind, questioning context and embedded histories in each frame. Pictures are largely the way in which we process worlds unlike our own,” she said.

Such a class is a natural progression for Lewis, who came to Harvard as an undergraduate intent on studying “the transformative power of the arts.” She recalled how her grandfather, Shadrack Emmanuel Lee, a painter and musician, was expelled from public school in 1926 for asking where “all of the African-Americans were.”

“His pride was always so wounded from the expulsion that he never went back to high school,” she said. “As a young person, I was impacted by his choice to become an artist after that event.”

At Harvard, she studied social studies and the history of art and architecture, writing her thesis on the resistance of artists of color in the 1960s and ’70s. She helped found the visual arts component of the Harvard Black Arts Festival, and she co-founded the Harvard Concert Commission. After graduating, she spent three years in England on a Marshall scholarship, working at the Courtauld Institute of Art and the Tate Modern in London, then got a job at MoMA. She left the world of curating to get her Ph.D. at Yale University, and published “The Rise,” a bestseller about the role of creativity and failure in art.

Aperture features about 200 images. Some of them (featuring some of the same artists, such as Lorna Simpson and Frazier) will be on display at the Harvard Art Museums. At the heart of both iterations is “Memorial to Martin Luther King Jr.,” the portrait by Benedict J. Fernandez of three young men taken on the day of King’s assassination.

“I find this image stunning,” said Lewis. “The [jacket] pins of King laid out on the bodies of these men, standing like stoic soldiers, hint at the unfurling of an archive. It’s emblematic of the aesthetic funerals that we would see in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement that tied art to contested citizenship.”

Some of the tragedy reads more subtly. In Russell Lee’s “Kitchen of a Farm Security Administrator’s Tenant Purchase Client” (1939), a woman attends to domestic work in a stark all-white kitchen.

“The homogeneity — the insistent whiteness of those cabinets — rhymes with the visual order that turned segregation into an imposed policy,” said Lewis. “There’s a light bulb at the center, but there’s no illumination. There’s a window that looks out onto nothing. It conveys how an image can give voice to the unspeakable.”