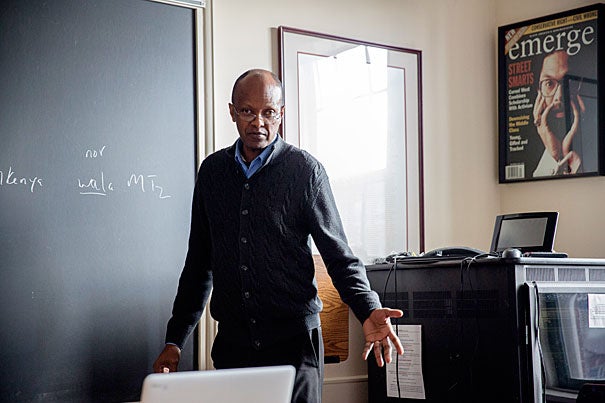

Linguist John Mugane, professor of the practice of African languages and cultures, is the director of Harvard’s African Language Program. “The importance of Africa cannot be denied,” he said.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

From Swahili to Bemba to Twi

African Language Program reflects two dozen ways in which a vast, rising continent speaks

Captivated by African storytelling traditions, Lowell Brower became fluent in Swahili and did research in Tanzania as an American undergraduate. When he wanted to expand his study to Rwanda and beyond, he realized he needed to learn Kinyarwanda, Xhosa, and Lingala.

So he came to Harvard.

“It’s the one and only university on Earth where I knew I could find people to teach me the African languages that I so desperately wanted to learn,” said Brower, now a doctoral student studying African languages, literatures, and cultures.

He can’t complain about the choice.

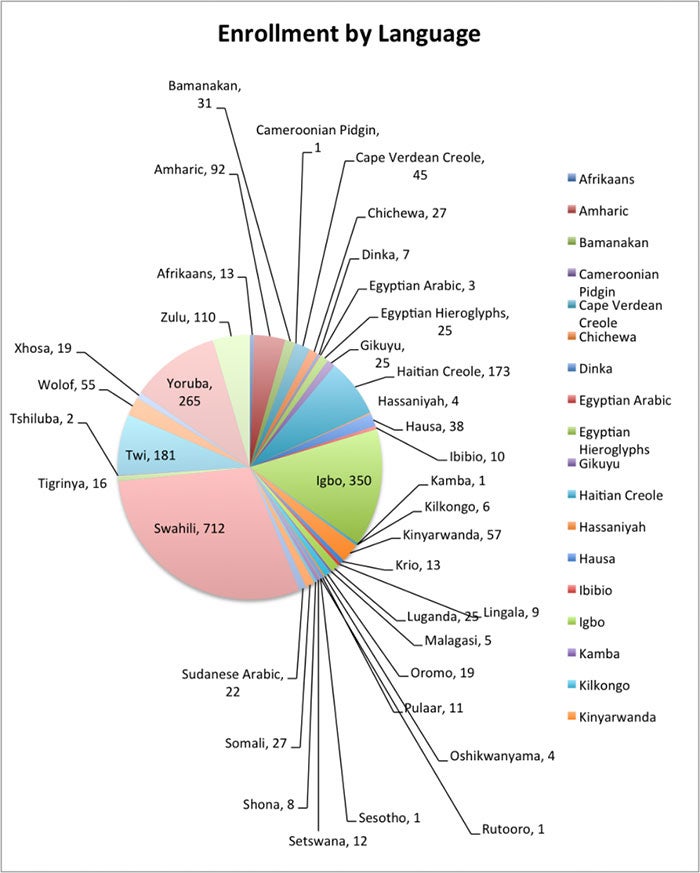

Each semester, the African Language Program at Harvard offers more than 25 languages ranging from Swahili, Gikuyu, Twi, and Yoruba (the most widely spoken languages in Africa) to the less-common Fon (spoken in Benin and Togo), Bemba (Zambia), and Tigrinya (Eritrea). It also teaches Jamaican patois and Haitian Creole, which are deemed nonstandard languages, and it once offered Cameroonian pidgin.

From Swahili to Twi to Yoruba: Africa’s multitude of languages

With this wide sampling that keeps expanding in response to student demand, Harvard’s has become the foremost African-language program in the Western Hemisphere, said Lawrence D. Bobo, W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Social Sciences and chair of the Department of African and African American Studies.

“This is the best, largest, and strongest,” said Bobo of the program. “Indeed, I know of no other like it anywhere else.”

When it was established in 2003, the department offered 10 languages to 40 students, and over the past decade it has taught 42 languages to more than 3,000 students.

The program’s growth underscores the rising interest in studying Africa, a vast and rich continent of 1.1 billion people that has endured wars and civil unrest, Islamic insurgencies, and public health crises, yet is still home to several of the world’s most rapidly growing economies.

“The importance of Africa cannot be denied,” said linguist John Mugane, professor of the practice of African languages and cultures and director of the program. “Africa is part of the human equation that can’t be left out.”

Interest in the region has also ballooned due to the emergence of Islamic extremist groups Boko Haram in Nigeria and al-Shabab in Somalia. The U.S. State Department considers some African languages “critical” to U.S. national security, and while the demand for more speakers of African languages has increased, the supply still lags.

At Harvard, student demand is the main drive for the broad diversity of African languages offered. Some students are children of African immigrants and wish to reconnect with their roots. Others want to travel around the continent, and some others who are pursuing academic projects are encouraged to learn an African language by their faculty advisers and by Mugane.

As a norm, professors of African studies urge students interested in the continent to learn one of its languages, said Mugane. “A serious understanding of any African topic starts with language study,” he said. “You can’t do African studies without talking to Africans in their own languages.”

In the past, U.S. universities often produced African experts who didn’t speak any African languages, a trend that Mugane likens to a kind of “malpractice.”

“I always tell my students to challenge the so-called African experts by asking them whether they speak any African language,” said Mugane. “Because the whole idea that you do research without speaking the language of the people you’re researching about is nonsense.”

Students take Mugane’s advice to heart. Take, for example, doctoral students Ian Copeland, Jessica Dickson, and Ayodeji Ogunnaike. Copeland studied Chichewa to do ethno-musicological work on Malawi. Dickson took Afrikaans and Xhosa lessons to research the South African film industry. Ogunnaike has been learning Yoruba to study religion in Yoruba society.

The students’ enthusiasm has pushed the program to widen its offerings. Faced with a dearth of local instructors in languages such as Dinka, Oromo, or Kikongo, Mugane came up with a creative response. He recruited natives of Africa, mostly college-educated, from Boston’s African communities, and trained them to teach in small tutorials. Supervised by Mugane, the language coaches teach basic grammar skills and vocabulary that fit students’ research projects, and provide cultural guidance to interact with Africans.

“Coaches become students’ research partners,” said Mugane. “They tailor lessons to students’ needs.”

Language coach and Zambian native Theresa Lungu has taught Bemba to three students over the past two years. She said she enjoys sharing her culture and teaching her language at Harvard.

“The new generation in Zambia is learning English,???? said Lungu, who works as an administrative assistant at Harvard. “But teaching Bemba here may help it being alive.”

Students generally become proficient within a year, said Mugane. They learn to understand, speak, read, and write, but the emphasis is on helping them develop oral skills. To showcase their progress, they’re required to participate in the biannual Theater Night, where they perform in plays they write with their coaches’ help. This year, students performed in 27 languages, including Zulu, Somali, and Sudanese Arabic.

Most of what students learn is practical and useful, said Avery Coffey, a sophomore majoring in economics with a secondary in African-American Studies.

One day recently Mugane was teaching students how to use comparatives and superlatives in his Swahili class. More than 20 students crammed the room and all of them came well prepared for the lesson. “Do you know how to say Harvard is better than Yale?” Mugane asked with a deadpan face. “Harvard ni bora kuliko Yale,” he said as students broke into laughter.

The program also maintains Africa’s Sources of Knowledge — Digital Library, which hosts African-language documents of literary and historical significance. Each year, it holds a conference in which scholars present research they have undertaken with help of African languages.

For Brower, who is now the head teaching fellow for the program Mugane leads, the decision to come to Harvard proved the right one. Learning African languages has enriched his life personally and academically, but he is especially proud of having followed Mugane’s recommendation.

“Academically, knowing several African languages has awakened me to the immense power and potential of Africa’s sources of knowledge,” said Brower. “And it has allowed me to share my research unafraid that someone in the audience might ask me the famous ‘Mugane question’: ‘Do you speak the language of the people you speak about? Can you write in the language of the people whom you write about?’”