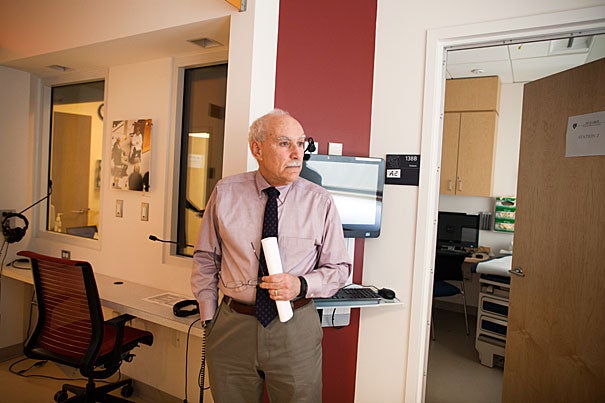

Cory Scott and Betty Paulsen (not pictured) are both standardized patients at Harvard Medical School’s Clinical Skills Center, which allows students to train with people acting like they are sick.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Real as a heart attack, almost

Acted-out medical conditions formative for future physicians

“What am I today? I’m spitting up blood.”

Cory Scott was matter-of-fact about his condition, as he sat at Harvard Medical School’s Tosteson Medical Education Center in January. “I have a heart condition because of rheumatic fever I had when I was a kid.”

Such an admission, on a campus surrounded by physicians — both accomplished and still in training — might ordinarily set off a rush to action, but Scott is no ordinary patient. He trained hard for his upcoming exam, to be performed by a student doctor in a nearby examination room … and then by another student doctor in the same room … and then another.

One might say Scott has been preparing for this serial examination — to be conducted by a total of seven student-doctors over more than two hours — for 14 years.

Scott works at the intersection of classroom and clinic. Trained as a “standardized patient,” he is part of an unsung group of actors who role-play the sort of diagnostic puzzles regularly faced by practicing physicians. The exercise keeps with the mix of clinical training and classroom learning that defines students’ four-year journey at Harvard Medical School (HMS).

Lessons are set at the Clinical Skills Center, a high-tech suite of examination rooms. Each room has a table, desk, and chair, along with equipment typically found in a doctor’s office. These rooms, however, are also stocked with two cameras, a one-way glass observation window, a red-glowing digital clock marking the 20 minutes given for each encounter — and a patient like Scott.

“For most [students], it’s an opportunity to put on a white coat, walk into an office, operate independently, and get immediate feedback,” said Edward Krupat, director of the School’s Center for Evaluation, which administers the simulated-patient program. “The idea is that students should feel that this is real.”

Patients are recruited and trained by the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, which provides standardized patient services for schools across New England.

While UMass runs the service, individual schools create the scenarios patients memorize to become truly “standardized” and provide a common experience for each student with whom they come in contact. A given scenario includes the patient profile — sex, occupation, and age — the medical issue involved, and details such as whether information should be revealed right away or held back to make the student doctor dig for it.

Patients go to great lengths to be believable, Krupat said, remembering a particular performer who broke down and cried at bad news — back pain was due to metastatic cancer — only to quickly compose herself in time for the next student. Another standout was a man portraying a Big Dig worker despondent over a construction-site death. When Krupat chatted with him during a break, he was thrown.

“I was so shocked at how normal he was,” Krupat said. “I couldn’t believe the difference.”

Students take the standardized patient examinations twice during their medical school careers, once in the second year and once just before the fourth. They are evaluated on communication, ability to take a medical history, and physical examination skills. Each student sees seven different patients during the examination, while patients eventually see all of the roughly 170 students in a class, according to Agnieszka Jackson, assessment coordinator for the Center for Evaluation.

As an actor living in Leicester, just outside of Worcester, Scott said he’s “completely blessed” by the work. In 14 years, he has come to see the exercises as more than a way to help cover the bills. Standardized patients, he said, are aiding the development of generations of doctors, in part through feedback.

That feedback is crucial, Krupat said. Students hear from the standardized patients on issues such as communication and interpersonal skills, and from faculty members about the more technical aspects of their performance. Faculty members view each encounter from the hallway outside the room, through the one-way window. Each session includes 15 minutes for patient examination and five minutes of feedback, before the student moves on to the next room and a new situation.

“No student likes being tested and watched and observed, but students say they love this,” Krupat said. “They ask why can’t they do more. They’re getting immediate feedback from someone who’s knowledgeable.”

The Clinical Skills Center could be the set of a medical drama, with white-coated students standing or pacing nervously outside examination rooms, stethoscopes draped around their necks. Inside, the standardized patients sit on the edge of tables, some reviewing notes and others just waiting, like thousands of patients in medical offices across the country, for the doctor to come in.

Betty Paulsen of Auburn, Mass., has been a standardized patient for 32 years and been to HMS “many, many times.” Paulsen, on this day suffering depression, said she’s seen a transition in the student body, from mostly male students to about half male and half female.

“Some of them are absolutely marvelous and some have a lot to learn,” Paulsen said. “Some, I say, ‘In 10 years, I wouldn’t mind them being my doctor.’”