“This project is part of a larger effort that Harvard and other institutions are making to clarify and highlight the role that native people played in our history and government,” said Daniel Carpenter, Allie S. Freed Professor of Government and director of the Radcliffe Institute’s social sciences program.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

A hearing for pleas to right wrongs

Scanning project seeks to digitize Native American petitions

More like this

There were ancestral lands to defend, and government treaty payments that never arrived. There were local churches that needed ministers, communities that wanted blacksmiths, and schools that lacked teachers. There were patterns of discrimination, insult, and inefficiency that needed attention and redress.

Though their voices are often missing from popular histories of the region, Massachusetts’ native peoples were never silent partners, Harvard scholars say. A new project seeks to restore their voices to historical and political scholarship by digitizing thousands of petitions to the Massachusetts legislature by and about the state’s native populations.

“So much history displays Native Americans as passive bystanders, as European Americans came in and industrialized,” said Daniel Carpenter, Allie S. Freed Professor of Government and director of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study’s social sciences program. “My hope is that we can amplify and better hear the voice of native peoples in American history — not least in Massachusetts and at Harvard. This project is part of a larger effort that Harvard and other institutions are making to clarify and highlight the role that native people played in our history and government.”

The project, funded through a $275,000 grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources, is a collaboration between Radcliffe’s Initiative on Native and Indigenous Peoples, the Harvard University Native American Project, the Yale University Indian Papers Project, and the Massachusetts Archives, where the petitions are held.

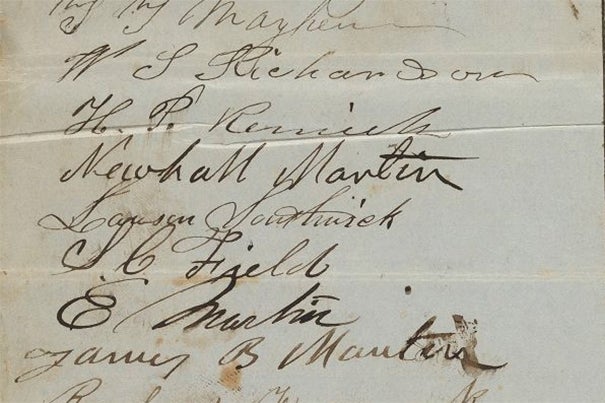

It involves transferring about 4,500 petitions written between 1640 and 1870 from the Massachusetts Archives to Radcliffe and the scanning center at Widener Library for digitization. By the end of the 18-month project, digital copies will be available on the Web for scholars in a wide variety of fields to review, Carpenter said. In addition, Yale’s Indian Papers Project will transcribe and annotate several hundred petitions, both making them easier to read and providing historical context.

As one begins to look through the petitions held in the Archives — as Carpenter has done with earlier projects on slavery and segregation — one is struck by the volume of correspondence between Massachusetts’ native people and the government, very little of which has been documented by historians and other scholars, Carpenter said.

“We’re just delighted this kind of partnership can be far-reaching. … We need to know what’s in these petitions.”

— Shelly Lowe

Native Americans in Massachusetts were a disadvantaged minority, Carpenter said, whose property, traditions, identity, and civil rights were under assault. The petitions provide historical documentation on matters such as land claims, discrimination, religion, requests for autonomy, the places people lived, and 19th-century social life, Carpenter said.

“They used the petition process to make claims upon the commonwealth and protect what resources they had,” Carpenter said. “There’s a lesson for contemporary politics on how a disadvantaged minority could use the political process to have a voice in government.”

Carpenter predicted that the petitions could be useful for scholars in fields ranging from history to religion to economics. In addition, the project includes an outreach component, which will devise ways for the petitions to be used in classrooms.

Many of the petitions, Carpenter said, appear to have remained unopened since they were first received by the legislature a century or more ago. Their unfamiliarity to scholars enhances the value of the scanning project, as it will make them widely available. In addition, he said, they are slowly deteriorating with time, so scanning will preserve their contents into the future.

“They’re decaying. If we didn’t do something, in 50, 100, 150 years they might be lost to posterity,” Carpenter said.

Petitioning the government was the most common method of airing grievances and concerns, Carpenter said. Petitions could come from individuals, groups, or entire communities. It is difficult to say what actions resulted from many of the petitions, Carpenter said, but he pointed out that even those that didn’t result in concrete legislative action often had an effect on the petitioners, helping them organize around a cause and building new community that could endure.

Shelly Lowe, executive director of the Harvard University Native American Program (HUNAP), said several New England tribes are supportive of the project, which has value to them as well as to scholars. HUNAP is acting as a liaison between the petition project and the tribes, who are potentially valuable allies to scholars examining the petitions. Some petitions are written in tribal tongues, or in phonetic English, that might be easier for native speakers to understand, Carpenter said. Even those written in standard English can contain place names and other words that tribal experts could help with.

Tribes could benefit as well, by gaining a greater understanding of events big and small that affected their people in the past, Lowe said.

“We’re just delighted this kind of partnership can be far-reaching,” Lowe said. “It was a way for the disenfranchised to put their concerns, wants, as constituent communities, [before] leadership so they can be looked at and addressed. … We need to know what’s in these petitions.”

The project, supported by the Mohegan, Mashpee Wampanoag, and Wampanoag of Gay Head (Aquinnah), includes both digitization of the petitions and consultation about them with tribes in Massachusetts and Maine, which was once part of Massachusetts.

“We felt we couldn’t do it without involving local tribes.” Lowe said. “It helps us to further unfold what history looks like within New England. We find an accurate and actual history either isn’t told or is told in a way that natives wouldn’t tell it.”

Upcoming events: “An Afternoon with the Poet Laureate of the Navajo Nation” will feature Luci Tapahonso at 4:15 p.m. on March 10, Sheerr Room, Fay House, 10 Garden St., Cambridge.

“The Native Peoples, Native Politics” conference on April 29 explores politics in Native American life today and includes an address by Murray Sinclair (Peguis First Nations), chair, Indian Residential School Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Canada.

The Radcliffe Institute is also holding additional events as part of the Initiative on Native and Indigenous Peoples. Visit its website for details.