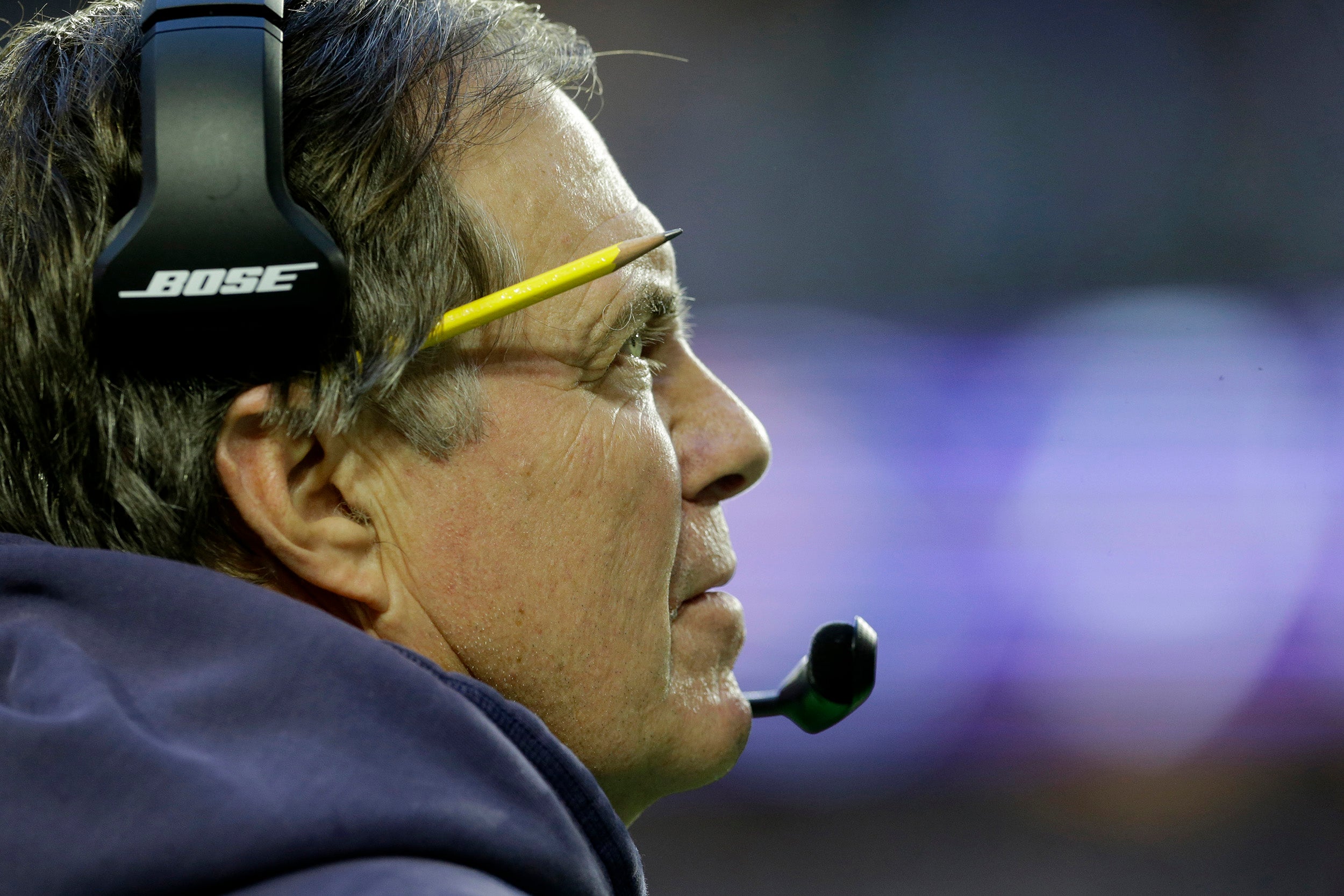

Doing his job

“An effective leader, first and foremost, has to be true to him- or herself and be authentic. I think Bill Belichick is being true to himself,” said W. Carl Kester of the Business School.

AP Photo/Patrick Semansky

Bill Belichick’s endlessly efficient management style holds lessons for business

In Bill We Trust. That’s the near-blind allegiance that most fans of the New England Patriots have for their head coach, Bill Belichick. It’s a rare expression of devotion in the notoriously harsh National Football League (NFL), where teams live or die on their won/loss records, and successful coaches can be one losing season away from being burned in effigy in stadium parking lots.

Under Belichick, the Patriots have racked up a remarkable record — 188 wins and 69 losses for a .719 winning percentage during his 16 seasons, the third-highest percentage in NFL history. The reigning Super Bowl champions, the Patriots have won four of six Super Bowls, six American Football Conference (AFC) titles, and 13 division championship games during his tenure. This Sunday, facing the Denver Broncos, the Patriots will play in their tenth AFC championship game in the last 15 years, with the winner going on to Super Bowl 50. They have been in the conference championship in seven of the last 10 seasons.

W. Carl Kester is the George Fisher Baker Jr. Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School (HBS) and is past faculty chair of the NFL Business Management and Entrepreneurial Program, an executive education program from 2005 to 2010 that offered guidance to NFL players who wanted to enter the business world after their football careers ended. The Gazette spoke with Kester about why Belichick, who graduated college with an economics degree, has been able to outperform his rivals for such a long time, and what businesses might learn from him about leadership and organizational management.

GAZETTE: What are some of the most important management principles or strategies of Bill Belichick that contribute to the organization’s sustained success?

KESTER: One, I just think he’s a coach who brings to every game a very clear vision of what it is he wants to have done. Maybe in some games he has a clearer or better vision than in others because he doesn’t win everything. But by and large, it’s a pretty clear vision built upon a lot of bone-crushing work and long hours and extensive analysis by him and the rest of his coaching staff.

Second, whatever he is or isn’t with respect to the media and communicating externally, I have a sense that he must be an extraordinarily effective communicator internally. This line we always hear, “do your job,” likely has a lot of meaning inside that organization for what is expected of the players. He’s able to take his vision and explain what it means for every single team player. Whether you’re quarterback Tom Brady or you’re a lineman or a defensive back or a special teams player, the vision translates into something every single player can make actionable. He also blends his communication with a fair amount of motivation, doing things that are intended and, I suspect, do inspire people, but also pique their personal pride and gets them going. My sense is he also really enlists the key player-leaders, everyone from the quarterback Tom Brady to the team captains, people like Matthew Slater, who’s a special teams captain. He uses these people very, very effectively to communicate that vision.

The third thing is what I’ll call “actionable preparation.” By that I mean a lot of analysis, so you really understand your opponent well and your own strengths and weaknesses well, and then lots of rehearsal. We may call that “practice,” but I mean literally setting up situations and doing a lot of scenario analysis about “if this, then what?” Not just “what does this formation signal to us,” but “when we see this particular package lined up in this way, what is the chess match that’s about to unfold in front of us, and how do we react there?” I think what he does with all that is he builds in his players, first of all, really detailed knowledge about what it is they should expect, but then he also gets them to understand what in the military they call the “commander’s intent.” It’s hard to map out exactly what everyone should do under every contingency, but if you know what the commander intends for you to do, you can then make judgments as an individual officer in the field as to what the right course of action is to achieve that intent. I think that’s what every single player does out there, blended with their detailed knowledge, and it gives them the confidence to act spontaneously.

And finally, Belichick strikes me as someone who really knows how to manage the risks. I don’t mean to imply that he doesn’t take any risks. He takes lots of risks, and some things that look quite risky to us may actually be him engaging in some risk management. He tends to avoid making the really, really big mistakes that will cost you the game or might even cost you the season. I also think he’s the kind of guy who deals with problems — he doesn’t postpone them — he deals with them right on the spot. Going back to the Super Bowl last year, Malcolm Butler got in during the fourth quarter because Akeem Ayers wasn’t quite working out, so he took a rookie and put him in place of a seasoned back. He’s also very empirically rational, so if he sees something that’s not working, he will adapt on the spot. He might even throw out the whole defense they’d been working on the previous week in the first quarter if he sees that whatever the opponent is doing is not aligning well.

GAZETTE: Belichick is well known for his belief in preparation, his deep attention to detail, and his laser focus on both the task at hand but also the longer-range implications of his decisions and actions. Is that what it takes to run a complex organization, or is he excessively obsessed because of the brutally competitive nature of professional sports? And are these traits a good model for CEOs?

KESTER: Leaders and directors come in all different styles and flavors, and I don’t think we can ever say one model is right for everybody. But effective leaders are, first and foremost, true to themselves and authentic to themselves. And I think Bill Belichick is being true to himself. From what I’ve heard and read of his years with the Cleveland Browns, he had come off many years being an assistant coach to Bill Parcells. He went [to Cleveland] and was his true self in terms of how he wanted to run the team, prepare the team, and this obsessive attention to detail, but he blended it with trying to be Bill Parcells. He wanted to be that kind of hard-nosed guy who was really demanding. It was not quite genuine; it did not lead to the kind of effective communication and esprit de coeur or relationships with his team that he now has with the Patriots. By the time he got to the Patriots, he figured out how to be his true self and be authentic, not try to be Bill Belichick in Bill Parcells’ skin, and that’s made a big difference.

There is an approach to leadership that says what matters most is execution. There are many people who’d say “I’d rather have grade A execution with only a B+ strategy than the reverse.” In the fog of competition, it’s often execution that carries the day. I think Bill Belichick is of that school of thought: If you can go out there and execute consistently, you won’t win every possession, you won’t win every quarter, you might not win even every game, but you’re going to win most games and you’re probably going to do pretty well in the long run.

GAZETTE: He is the team’s absolute, singular authority in the public realm but behind the scenes is known to delegate authority to a circle of trusted coordinators and assistants with specific expertise, and he gives them power to manage key aspects of the team. Why operate that way, and is this seemingly contrary dynamic a good strategy to follow?

KESTER: Delegation only works consistently well if you’ve got great people around you. So credit Bill Belichick but also the entire Patriots ownership and management for building that pool of talent amongst both coaches and other support personnel as well as the players. Once you’ve got that, building a sense of trust with those people so they feel empowered to exercise their own analyses and creative thinking and exercise their judgment is bound to be a good thing. This is a field, not unlike the performing arts, other sports, and certain kinds of companies and businesses that operate in a fishbowl, where it’s really tough to stay focused and “doing your job.” With Belichick being the somewhat parsimonious, to put it mildly, outward-facing person for the team part of the Patriots (as opposed to the business end), he creates trust and confidence in the assistants to do what they’re doing behind the scene and out of the glare of public scrutiny. Belichick wasn’t born a head coach. He had his days of doing the hard work, the detailed analyses and knowing that he probably saw stuff that the head coach didn’t, so he probably values that in other people. It doesn’t surprise me at all that he would cultivate that inside the organization.

GAZETTE: Because the Patriots have been so successful for so long, they don’t get the opportunity to sign the top college recruits every year and must make do with lesser talent. Many say the team is able to still produce at a consistently high level is because of Belichick’s approach to hiring and his emphasis on maintaining a strong “team first” culture. How important is culture for a business and why? How hard is it to accomplish when the pool of qualified workers is so limited?

KESTER: The culture of the Patriots is absolutely of paramount importance. We can talk all about the individual skills and attributes of Bill Belichick as a coach-leader, but there are several conditions precedent that make that work well, and one of them certainly is the culture there. It’s absolutely huge, not just in sports, but in business and even here at Harvard and in academics. Culture is where you infuse people with the values, the attitudes, the work ethic, the sense of responsibility to themselves. In the case of the Patriots, it’s to teamwork. But in other settings it might be a sense of responsibility not only to your other employees, but to your customers, to other stakeholders. Here in an academic setting, it’s a sense of responsibility to your students, your colleagues, other scholars in your field, and so on. The more you’re constrained in your ability to hire simply the top talent, I think the more important the culture becomes, because the culture can take talent that’s good, even if not the very, very best, and leverage it into something where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. That’s what the Patriots do. They work really hard to get people who are a good fit, who they believe will have a good lockerroom presence, and weed out the knuckleheads. I think that’s goes miles and miles to helping them achieve what it is they want to do. They’ve made the team a true meritocracy. If you deliver, you play; if you “do your job,” you play. You may not play in the position that you were picked up for, but they’re going to find a place for you to contribute if you can do that. Confidence that you’re in a meritocracy probably enhances the culture they’ve got going. This is something other organizations can learn from. Culture is crucially important, but too often people think that corporate culture or university culture is somehow inherited, or it evolves according to some dynamic laws of its own, or it’s endemic, but it really isn’t. It’s hard to change, but a leader who’s really determined to change it and then uses the hiring, rewards, and retention processes to bring about that culture change can do it. It can be a very powerful tool to improve performance.

GAZETTE: In a 2005 HBS case study, Belichick said he realized that on an NFL team the most important relationship is between owner and coach. Why do you think his relationship with owner Robert Kraft, MBA ’65, is so important for organizational success, and is there a parallel in the business world?

KESTER: Going back to his early days, it appeared that Bill Belichick and owner Art Modell, when they were at Cleveland together, just didn’t work out. Bob Kraft is very different. Bob Kraft is a very astute businessperson (one of our MBA alumni, along with his son, Jonathan, ’90). He is someone who really does understand that when you have the talent there, empower them, support them where you can, nudge them if they need it, but otherwise let them go. I think Bob Kraft is savvy enough to understand when he’s got a good thing going. There’s another guy we don’t think of as management, but the quarterback effectively is. Brady does more than just throw the ball; he really sets the tone and contributes, I’m sure, in a whole variety of ways to creating the game plan, the vision of what’s going to happen. You’ve got a trio here that’s really done incredibly well.

GAZETTE: Most NFL teams expect the head coach to serve as the public face of the organization and to push positive marketing messages to the media. Given his taciturn style, clearly Belichick doesn’t view himself as that kind of brand ambassador. Doesn’t that attitude detract from the organization?

KESTER: That’s a really interesting part of his personality and role here. It gets back to the nature of the kind of communicator he is. He usually has one or two things he wants to get across, and once he does that, that’s it. You remember the interview last year after the drubbing [by the Kansas City Chiefs, Belichick said repeatedly] “we’re on to Cincinnati.” On some level, that was a little bit in your face, but on another level that was Bill Belichick being true to himself. He has a message, he’s going to stick to his message, and he’s going to say it as many times as he has to for the audience to get the picture. I have a feeling Belichick is the kind of guy who tends to measure himself by his own yardstick. I don’t mean that he’s uncaring about what other people think altogether, or that he’s arrogant. He doesn’t particularly want to be disliked, but he’s going to be the way he is. He’s the best brand ambassador the Patriots ever had because he wins championships. If he was a mediocre, .500 coach, it would be different, but he’s not. He can do what he does — has the margin to do what he does with the press — because he wins. If this complex set of things — the culture, the talent, the communication, the risk management — if it’s all working and hanging together and he wins, then the PR wrapper you put around it just isn’t nearly as important as having that parade through Boston after you win a Super Bowl.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.