Harvard’s Houghton Library has acquired Henry David Thoreau’s notes from the scene of the shipwreck that killed social reformer and writer Margaret Fuller.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Uncovering what Thoreau uncovered

Report on Margaret Fuller’s death is acquired by Houghton

Some might say the pioneering feminist, literary critic, social reformer, teacher, and war correspondent Margaret Fuller died as she lived, determinedly on her own terms.

On a journey back to the United States from Europe, Fuller’s ship, the steamer Elizabeth, ran aground off New York’s Fire Island during a violent storm in the early hours of July 19, 1850. According to Megan Marshall’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, Fuller stood firm with her husband and 2-year-old son on the sinking deck.

“Margaret would not leave her family; they would not leave her. Surely first mate Davis would return with the lifeboat now visible on shore,” wrote Marshall of Fuller’s plight and the sailor who had managed to swim to land.

But incapable of navigating the boat alone in the rough waves and unable to recruit others to help him, Davis didn’t return and Fuller drowned with her family only 50 yards from safety.

Her death at 40 was a blow to Transcendentalism: From 1840 to 1842 Fuller had edited the movement’s main publication, “The Dial,” alongside Ralph Waldo Emerson. Fuller’s friends and colleagues rushed to the site, desperate to recover the family’s remains. They were also anxious to find an account of the rise and fall of the 1849 Roman republic — “what is most valuable to me if I live of any thing,” Fuller had written of her last manuscript. One of those travelers was Henry David Thoreau, sent by Emerson to “go, on all our parts, & obtain on the wrecking ground all the intelligence &, if possible, any fragments of manuscript or other property.”

Fuller’s body and manuscript were lost to the sea. But a recent Houghton Library acquisition is shedding new light on the tragedy and on what Thoreau found as he wandered the beach for clues and interviewed survivors.

A found link

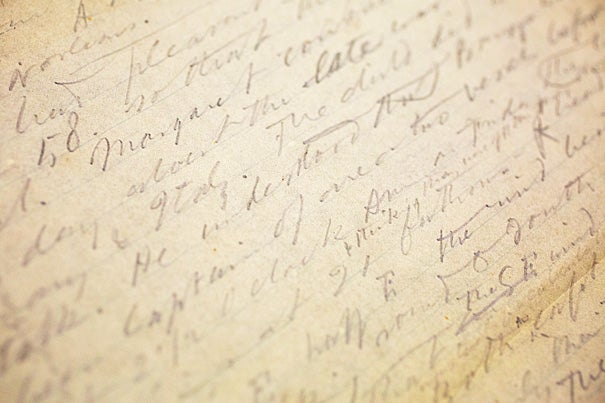

In May, the library purchased nine leaves of a largely unknown manuscript: Thoreau’s notes taken during his shoreline search. The pencil-scrawled, double-sided pages contain vivid descriptions of Fuller’s last moments, related to Thoreau by witnesses; they also describe how scavengers eagerly snatched up belongings that had washed ashore.

“The thieves told me that they withdrew a little & divided the spoil — (while the friends of the dead are seeking their remains) — this will do for your child & that for your wife — these were the expressions which they themselves quoted,” wrote Thoreau. “I found the young men playing at dominoes with their hats decked out with the spoils of the drowned.”

The manuscript had been transcribed by Thoreau’s contemporaries, and the resulting story of his search has been recounted by Boston University historian Charles Capper in “Margaret Fuller: An American Romantic Life, The Public Years” (2007). Capper was the first scholar to see and use Thoreau’s report, which he discovered in a contemporaneous copied version in a collection at the Boston Public Library. But the original manuscript is a boon for both Thoreau scholars and for Harvard. The pages directly link Houghton’s Thoreau, Emerson, and Fuller collections.

“Here’s Thoreau, he is being sent by Emerson, also a very important figure to our collections, to investigate the death of Margaret Fuller. And the Fuller papers are here,” said Leslie Morris, the curator of modern books and manuscripts, who helped acquire the manuscript. “It really plays to three of our major figures here at the library. It brings them together.”

Scholars have long been aware that a 20-volume edition of Thoreau’s works released by Houghton Mifflin in 1906 included a little something extra. Bound into the front of the first volume in each of 600 special sets were original pieces of a Thoreau manuscript. The practice was fairly common at the turn of the century by publishers eager to boost sales, said Morris. “But it creates a nightmare for people who want to actually work with the manuscripts, because you’ve got pieces.”

Fortunately, Harvard’s acquisition appears largely intact.

More like this

Unlike so many other sets from 1906, many of which had only a page or two of original manuscript, this set, No. 1, contained nine leaves — 18 pages of notes in total — with a linear narrative documenting in detail what Thoreau had previously only summarized.

“Until this manuscript surfaced, Thoreau’s most detailed account of his engagement with the event was in a single brief letter to Emerson, also in the Houghton Library,” said Beth Witherell, who directs The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau, a project at Davidson Library at the University of California, Santa Barbara, begun in 1966 to provide accurate texts of Thoreau’s works. “Thoreau described parts of his experience in his journal and in ‘Cape Cod,’ but he didn’t explicitly connect those descriptions with this event. The new manuscript confirms his Fire Island experience as the source of those descriptions.

“In terms of our understanding of the effort that Thoreau went to in his attempts to discover what had happened,” she added, “this is a big discovery.”

Fortunately, readers can refer to Witherell’s transcription of the text instead of trying to decipher Thoreau’s swooping script on their own. Having worked since 1974 on Thoreau manuscripts, she is an expert at decoding his often-cryptic handwriting. The work is exciting, she said, because the manuscripts represent “what’s left of a physical connection to Thoreau.”

An examination of the new manuscript offers up both the thrill of seeing Thoreau’s hand on the page, and insights into his process. While the author is supposed to have made “fair copies” of the account, edited versions written in ink, these pages, experts agree, are almost certainly the notes he jotted down on site. The key clue: They were done in pencil.

“In those days they didn’t have fountain pens,” said Witherell. “If you were going to write in ink you had to sit down with a bottle of ink, and Thoreau usually used a quill pen.”

After numerous revisions a cleaner version was produced for friends.

“There’s some rearranging. There are cancellations. There are also use marks, which I see in a lot of his manuscripts,” said Witherell. “These are vertical lines Thoreau used to remind himself that he has used that part in the next iteration of the account.”

Treasure in the margins

Once at Harvard, the manuscript yielded more than had initially met the eye.

Working with Morris, Debora Mayer and Karen Walter, conservators at the Weissman Preservation Center, agreed to remove a non-original paper border surrounding each of the nine delicate leaves. The paper frames had begun to tear and were in turn tearing the manuscript.

“Our goal is usually not to make changes like that,” said Walter, who adheres to the conservator’s creed: Save any material that might be of use to a researcher. “But in cases where the original is going to suffer damage because of the way it was handled or the way it was later treated by someone else, then we are more likely to intervene.”

When Walter gently lifted the frames, entire sentences by Thoreau, long-hidden notes scribbled along the edges of the pages, were revealed.

“I was surprised to see how much text there was,” she said, “and happy we did the right thing.”

Using a fine Japanese paper treated with adhesive and brushed with water, Walter repaired the small tears. She also worked with the library’s digital-imaging team to create “surrogate” copies of the manuscript, high-quality images printed on paper the same thickness as the original that were reinserted into the first volume.

“We wanted to keep the original feel of the piece,” said Walter, “while protecting the original notes.”

Like Witherell, Walter’s favorite part of working on the manuscript was the thrill of seeing the indentations the author’s pencil made on the page. “You get a sense of Thoreau sitting there, writing,” Walter said, “pressing hard into this paper.”

For Witherell, who has been trying for years to track down the original pages from the 1906 sets, Houghton’s addition is a rare find and an important piece of literary history.

“This manuscript is a great big deal for those who study 19th-century American literature and history, and in particular for students of Thoreau and of Fuller. It’s very unusual for long Thoreau manuscripts to come on the market, and it’s a wonderful surprise to find so much new material. Nine leaves … that’s a lot.”