More than help for their hair

Schlesinger Library receives letters from African-American servicewomen

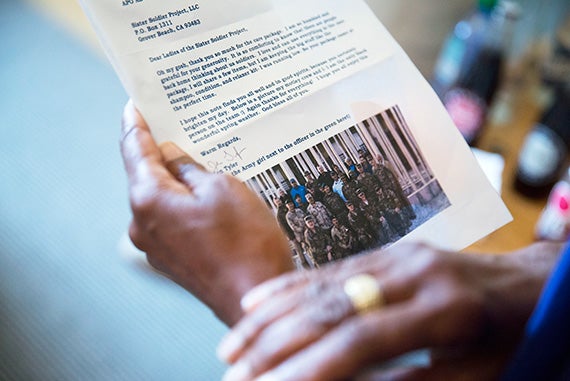

“Thank you so very much because my head looks like a hot mess,” begins a letter written to Myraline Morris Whitaker, a California-based hotelier who until two years ago ran the Sister Soldier Project, a grassroots campaign geared at providing hair products to African-American female soldiers to help them comply with military guidelines. The letter’s author was one of those soldiers.

“If hair is longer than the ears, it has to be pulled back and tucked under, and as a black woman I just don’t understand how that happens without the right product,” said Whitaker.

She logged on to anysoldier.com, a website where members of the military can list their needs. There, she identified black female soldiers appealing for hair products, boxed up four packages for them, “patted myself on the back,” she said, and that was that.

Until the letters started arriving. Grateful letters, letters with stories.

“The hair goodies are much needed, especially since the dust storm season has begun,” read one letter. “So many women of color ask me how I am able to maintain my hair while being deployed, and I tell them it’s because of your products you send to me.”

“These women never complained,” said Whitaker. “They just talked about their lives in the service. They were happy to be there. They talked about the families they’d left behind, and they’d send pictures of their children.”

Whitaker couldn’t turn away from this newfound mission. In 2008, she formally launched the project, shipping more than 1,000 packages totaling upward of five tons of hair and beauty goods.

Now Whitaker’s cache of letters and ephemera will live on at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study’s Schlesinger Library, which recently hosted a reception commemorating its newest acquisition.

On hand was Robert Mitchell, assistant dean for diversity relations and communications, a longtime friend of Whitaker from their days attending Syracuse University. After Whitaker’s collection was refused by the Smithsonian Institution, Mitchell suggested the Schlesinger Library, dedicated to documenting the lives of women.

“The Schlesinger doesn’t have a lot about women in service after World War II, and this is really a segment — small that it may be — that someone will find interesting,” said Whitaker.

And that’s the big victory here, said Whitaker. “There’s a segment of our population who serve this country who will have their voices heard,” she said. “Someone should hear this story.”