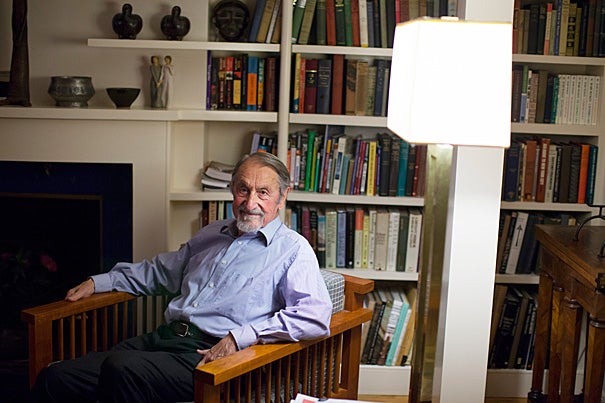

“Martin Karplus — The Invisible Made Visible,” a documentary film of his life, is the third in a series called “The Eviction of Intellect.” Karplus ’50 (photo 1) is Harvard’s Theodore William Richards Professor of Chemistry Emeritus. Photos from his childhood mark the making of the 2013 Nobel laureate in chemistry.

File photo (1) by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer; (2, 3) courtesy of Martin Karplus

Karplus on film

Nobel laureate featured in ‘Eviction of Intellect’

Martin Karplus ’50 is Harvard’s Theodore William Richards Professor of Chemistry Emeritus, the 2013 Nobel laureate in chemistry, a widely exhibited photographer, and an experienced chef who plans the evening menu on his walk home every day. He likes to joke, “The only chemistry I really do is in the kitchen.”

Now the 85-year-old can add “movie star” to his resume, after the May 25 premiere of “Martin Karplus — The Invisible Made Visible,” a documentary film of his life, and third in a series called “The Eviction of Intellect.” It was broadcast in German on both ORF III, a public television station in Vienna, and on ARD, a consortium of public television stations in Germany. (An English-language version will be ready by mid-June, but its American distribution has not been scheduled yet.)

The 45-minute film tells the story of Karplus being harried out of his childhood home in Austria by the Nazis; his upbringing in suburban Boston; his awakening to science (partly through bird watching); and, eventually, his landmark work in molecular dynamics and bio-molecular simulation.

The movie started with a plan by the director last July. Filming began in September in New York, then moved on to San Francisco; to Cambridge, at the Harvard lab where Karplus is still active in research; to his boyhood haunts in Brighton and Newton; and then to Berlin and France, where Karplus has a family chalet in Chalmont.

Video was shot in the French village of Illhaeusern, too, a dot on the Alsace map. Twenty years ago, Karplus worked there for two weeks in the kitchen of the three-star Auberge d’Ill, a riverside inn near the border with Germany. The chef showed Karplus the trick to making goose-liver pate, remarking on film, “You’re the only Nobel Prize winner who has worked in my kitchen.”

Behind the documentary is a narrative of joy, danger, luck, escape, and hard work stretching back more than 75 years.

In the spring of 1938, Karplus’ father, Vienna businessman Hans Karplus, foresaw the racial violence in store for the Jews of Austria. (Kristallnacht, a national wave of anti-Semitic pogroms, swept through Nazi territories that November.) So he arranged a family “ski trip” to neutral Zurich.

On March 17, his wife, Lucie, and sons Robert and Martin (who had just turned 8) slipped away unharmed. But Hans Karplus was detained and imprisoned in Vienna. In order to join his family, he had to relinquish everything to Austrian Nazi authorities: house, car, money, and rights to a big inheritance. His brother Eduard, then living near Boston, had to pay a ransom of $5,000 — equivalent to more than $80,000 today — to complete the deal. Hans Karplus escaped with only his stamp collection, and sold it much later in the United States. It covered two months rent.

In the two previous “Eviction” films, director Eberhard Büssem — a German-born historian of modern Europe — told the stories of others who were expelled from Vienna and went on to lead similarly worthy and useful lives. “All of us Jews,” said Karplus, “all of us driven out of Austria.”

In an email from Austria, where he was filming last-minute scenes with Karplus, Büssem said, “The idea of the films is to create a witness of the forced exodus and killing of human beings, the robbery of property, the violation of elementary human rights and also the loss of intellect.”

Karplus has been in Austria since early May, on a visit to his native city that has been marked by considerable irony. The man who was declared racially unfit in 1938 returned this month to receive the keys to Vienna; an honorary doctorate from the University of Vienna, which celebrates its 650th anniversary this year; induction into a national academy; and Austria’s highest national honor for science and art — the Order of Merit, or Ehrenzeichen —from Austrian president Heinz Fischer. “It’s a little late,” said Karplus in German, accepting the honor with a touch of dry wit, “but perhaps it’s good for reconciliation whenever you say yes.”

Karplus, an avid photographer since his 20s, is also being honored with an exhibition of his work at the University of Vienna. His photography earlier appeared at two Austrian cultural venues, in New York and in Washington, D.C., as well as in post-Nobel shows in Oxford, Paris, Berlin, and elsewhere. It is through photography, said Karplus at his Cambridge home before departing for Europe, that he tries to create “the invisible made visible” — his “leitmotif” as an artist.

Karplus’ public celebration by the city of his birth brought with it the somewhat fraught issue of having to make public remarks. “It’s complicated,” Karplus said, since memories still well up from the 1930s, along with doubts that Austrian anti-Semitism is gone — a point he made in a scathing interview with Austrian radio after the Nobel ceremony in 2013. “In some ways, you can say they waited a long time — more than 75 years. It’s only now that I got a Nobel Prize that they realize what they did.”

Büssem reflected that at least Germany and Austria, “late but better than never,” have admitted guilt and accepted responsibility for “all the atrocities of the Nazi regime.”

The visit to Vienna brought back a childhood of loving relatives, books, and outdoor play. While there, Büssem planned to film Karplus on the outskirts of Vienna, where he lived when he was very young, and at the site of the fango (mud) sanatorium that Dr. Samuel Goldstern, his maternal grandfather, ran for patients all over the world with nervous disorders.

Karplus was born in 1930 to a family of secular Jews, whose indifference to religion made their expulsion from Austria all the more shocking. The family was notably accomplished. His paternal grandfather, Johann, a famous neurologist, played a role in the discovery of the hypothalamus. His grandmother on that side, Valerie von Lieben, grew up in a palatial apartment on Vienna’s Ringstrasse. Her brother Robert developed the cathode ray relay to enhance the sound quality of telephones, and her wealthy grandfather Ignaz Lieben in 1862 founded the Lieben Prize for science, known as the Austrian Nobel Prize.

His uncle Eduard Karplus, who came to the rescue in 1938 with $5,000, invented the Variac autotransformer used to step up or down voltages. (It is still used today.) And his great-aunt Eugenie Goldstern on his mother’s side was one of Europe’s most acclaimed ethnologists, an expert in Alpine village life and folkways whose prying fieldwork a century ago in the remote French village of Bessans earned her the nickname “The Spy.” Karplus remembered seeing her often. “She would have toys and play with us.” In 1942, at age 58, she was killed at Sobibor death camp in Poland.

Büssem, born in 1941, said that one message of his latest “Eviction” film can be conveyed in numbers. It premieres in May, 70 years after the end of World War II in Europe, and 77 years after Hitler snatched power in Austria. In all, 150,000 Jewish Austrians had to emigrate — 10 percent of them scientists and nearly half of the nation’s physicians. For Austrians, he said, the forced evictions were “a terrible loss of intelligence.”

For Americans, the émigrés represented a “great benefit of talents,” said Büssem: landmark thinkers such as Albert Einstein, and gifted children, like Karplus, who reached full bloom after finding refuge in the United States.

Büssem’s two previous “Eviction” documentaries underscore what Austria lost and America gained.

“Carl Djerassi — Father of the Pill” (2008) is about the chemist, art collector, novelist, and playwright most famous today for formulating the birth control pill and for his work on antihistamines. Djerassi escaped Vienna in 1938. The next year, he immigrated to America with his mother. Between them they had $20.

Djerassi also figures in the second film, “Eviction of Intellect: Four World Stars of Science.” The others are chemist and philanthropist Alfred Bader, Ph.D. ’50; 1998 Nobel laureate in chemistry Walter Kohn, Ph.D.’48; and British historian Peter G.J. Pulzer.

Bader and Kohn escaped from Austria on the famed Kindertransport, a British rescue scheme that from 1938 to 1940 sponsored asylum for unaccompanied Jewish children living in Germany or Nazi-annexed countries like Austria.

With Karplus part of the “Eviction” series, three of Büssem’s five subjects — and all three Nobel laureates — are graduates of Harvard. But none of the others, perhaps, know how to make good goose-liver pate.

“Eberhard wanted to show the different sides of me,” said Karplus of the director. “I have a life of many parts.”