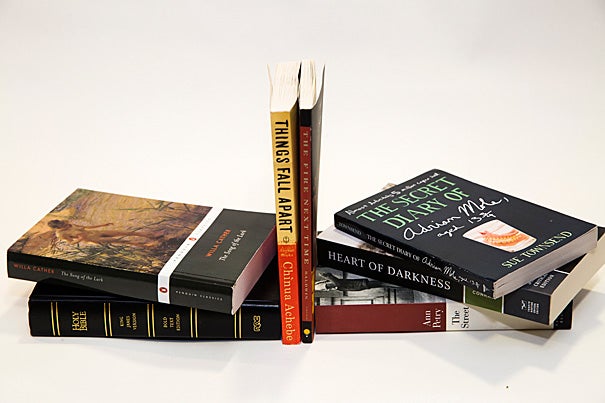

Faculty members selected the books that played — and continue to play — formative roles in their lives. Their responses include everything from teenage fiction — “The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾” — to headier tomes like the Bible.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

The books that shaped them

As summer reading time nears, six professors reflect on their most memorable titles

While the best literature is undoubtedly universal, books are also deeply personal. The Gazette spoke with six faculty members about the formative books that shaped their lives and even their scholarship. From the quirky to the downright serious, their responses offer a varied and candid look at what resonates.

Elizabeth Hinton

Assistant professor of history and of African and African-American studies

Ann Petry’s “The Street” has haunted me since my days as an undergraduate. I’ve always been interested in how societies are shaped by violence, and by what drives individuals to commit acts of violence against each other and against institutions. Published in 1946, Petry’s novel illuminates the ways in which a combination of socioeconomic realities can ultimately converge in deadly outcomes for ordinary Americans with modest and admirable ambitions. “The Street” tells the tale of Lutie Johnson, a young single mother in postwar Harlem, and was the first book by an African-American woman to sell over a million copies. Beneath the jazz clubs, underground economies, and cast of villains Petry introduces to her readers lies a troubling indictment of the limits of inclusion and equality in the U.S. Initially Lutie believes that if she adheres to the principles of thrift and hard work stressed by Benjamin Franklin in his autobiography she can provide a better life for her preadolescent son. Lutie quickly discovers, however, that her marginalized social status makes it nearly impossible to realize the promise of Franklin’s American dream. A tragic mix of individual and structural forces thwart Lutie’s aspirations at every turn, eventually turning her desperate and angry enough to commit murder. The novel still resonates strongly, and its prose is still sharp and disarming, as many of the barriers Lutie confronts remain for other women, racial minorities, and low-income Americans. So every time I return to the 116th St. Petry imagines I gain a new set of insights into past and present conditions. It’s not exactly beach reading, but perfect for a rainy summer day or en route to a far-away land. Be warned: The novel’s abrupt ending will leave you unsettled and searching for a resolution that is still hard to find, both in Petry’s work and in our society.

David C. Parkes

George F. Colony Professor of Computer Science and Harvard College Professor

Like every preadolescent boy growing up in England at the time, I was fascinated with “The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾,” written in diary style by Sue Townsend. Not only was Adrian dealing with acne, falling in and out of love, and difficult parents, but he was also worrying about the topics of the time, including the Falklands war, finally finding the Falkland Islands on a world map hiding under “a crumb of fruitcake.” Townsend managed to weave together a narrative of bullying, teenage angst, and politics, and it all seemed fabulously grown-up. One of my favorite quotes: “Perhaps when I am famous and my diary is discovered people will understand the torment of being a 13¾ year old undiscovered intellectual.” I’m fairly sure I started writing my own diary.

Carol Oja

William Powell Mason Professor of Music

Books speak to us for many reasons, sometimes because we see reflections of ourselves — or parts of ourselves — in their narratives. For me, Willa Cather’s “The Song of the Lark” has long been such a text. I first encountered it as a teenager, during summers of omnivorous reading, and every now and then I return to reflect on its images of immigrant fortitude and escape to a world of ideas. Each time, I learn more about myself. While Thea Kronborg, the book’s heroine, was born at the turn of the 20th century and became an opera star, I hardly dare pick up the mic for a night of karaoke. Rather, as an adolescent in a northern Minnesota mining town — thoroughly a man’s world at the time — I was mesmerized by a female author writing of female artistic creativity, by a book that genders professional success as female. Thea is defined by what she has achieved rather than her love interests. Equally compelling to my younger self was Thea’s journey from Scandinavian roots in a frontier outpost to the startling stimulations of a major city. “The Song of the Lark” was my “Lean In.”

Michael VanRooyen

Director, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative; professor, Harvard Medical School and T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Just as the opportunity to travel abroad early in my career has been a moveable feast, some of the early books I have read have stayed with me, and influenced me, throughout the seasons of my career. Hemingway in particular made me reflect on the deep desire to see the world (“The Sun Also Rises”) and contend with war (“A Farewell to Arms”). But, more than Hemingway’s epicurean adventures, I love reading Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” and then turning to the contrast of Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart,” both helping me gain a greater sense of the beauty and tragedy of Africa, as I’ve traveled the continent for many years. Finally, and closer to home, John Irving’s quirky “A Prayer for Owen Meany” and John Kennedy Toole’s “A Confederacy of Dunces” have given me characters, comical and complicated, to carry with me and remind me that life is not always so serious.

Meira Levinson

Associate professor of education

One book that has exerted a profound impact on me is James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time.” It contains two essays, the first of which is a gorgeous, heart-rending, shake-you-to-the-core letter from Baldwin to his 15-year-old nephew, “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation.” In profoundly intimate prose, it condemns not only white Americans’ racism against black Americans, but also their/our professions of “innocence” about the existence and effects of such racism. Tragically, the book holds up as well now, more than 50 years on, as it did at its initial publication. I hope that the spasm of publicity around Ferguson, Cleveland, New York, South Carolina, and Baltimore might bring about more lasting change, but I confess I’m pessimistic. I first read “The Fire Next Time” as a young teacher in an all-black middle school in Atlanta. It helped me appreciate the stunning trust and even love that my eighth-grade students showed me, a white woman coming straight from Yale and Oxford with barely a clue about their lives. It also solidified my commitment to trust and love my students back, to try to understand their lives and hopes and sorrows, and to do everything I could to help them achieve those dreams, not only for themselves but also for their families, communities, and the nation as a whole. Now that I’m preparing future generations of educators and educational leaders at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE), I try to help them reflect on their ethical responsibilities as they learn to change the world. In doing so, I often assign “The Fire Next Time.” It seems to resonate as powerfully with my students at HGSE as it did when I was a young teacher in the field — and as it continues to resonate with me today.

Jelani Nelson

Assistant professor of computer science

For me, as a Christian, the book that’s had the largest impact on me is, by far, the Bible. It has informed nearly every aspect of my life, especially interpersonal relationships. It teaches me of God’s love for mankind, and that I should try my best to emulate this in my love for others. It teaches me to obey the golden rule of treating others as I would want to be treated. It teaches me to view others as more important than myself, and to look out for others’ interests. Lastly, several corollaries naturally follow from these, such as generosity and kindness toward others, and advocacy for the disenfranchised.