The “Tangible Things” undergraduate and HarvardX course is the brainchild of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, the 300th Anniversary University Professor and a Pulitzer Prize winner for history, who said the main idea behind the course is that “any object can become an entry point into historical investigation. The shoes on your feet, the chair you’re sitting on, light fixtures in the room — common things have stories.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Scholarship of things

Ulrich makes case for the narrative of objects

Addressing an audience at the Harvard Ed Portal, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, the 300th Anniversary University Professor and a Pulitzer Prize winner for history, said that many objects in Harvard’s collections defy easy categorization.

Consider, she said, the tortilla.

“It’s one of my favorite objects in Harvard’s museums,” she said of the University’s 118-year-old tortilla, which is kept in the Harvard University Herbaria. “It’s a botanical specimen, or sort of a botanical specimen, that became an ethnographic object, but is now a historical document. It’s led our students on many adventures: not just into food history, but into the history of ethnic conflict, the history of immigration, the history of migration on both sides of the Mexican-U.S. border, and so on.”

Harvard’s four centuries of history, together with the depth and breadth of its holdings, mean that many items reward a more up-close examination, yielding insights on world history and the University itself.

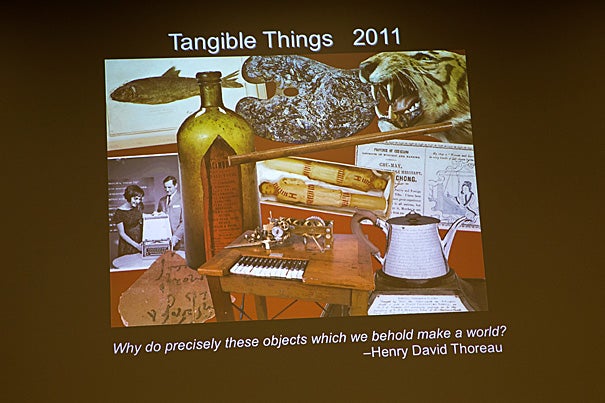

That concept, Ulrich said, led her to create the “Tangible Things” undergraduate course at Harvard, which grew into the HarvardX offering of the same name. Ulrich said the main idea behind the course is that “any object can become an entry point into historical investigation. The shoes on your feet, the chair you’re sitting on, light fixtures in the room — common things have stories.”

But it’s easy to miss out on those stories. Some students never enter a museum during their studies, and those who do often experience only brief glimpses into Harvard’s vast holdings.

“In the 19th century, many of the fields that our students study didn’t exist,” Ulrich said. “They grew out of the collecting of natural things. Anthropology developed out of collections, for example. By the end of the 19th century, you had very specialized museums — zoology museums, history museums, technology museums, and so on.”

Ulrich has worked to break down those barriers and make connections among a large pool of items, and across all levels of campus life. “Our goals were to engage students with physical things and to break down categories between objects, to make people more aware about the world in which we live. We wanted them to think across categories, to pay attention to their own tangible world, but also to think about Harvard differently,” she said.

Robert Lue, faculty director of HarvardX and the Ed Portal, and a professor of the practice of molecular and cellular biology, introduced Ulrich as “one of the stars in the firmament” of Harvard’s History Department.

“When we think of the objects we see in a museum, we tend to think of things that are incredibly precious as the only things that have value and power,” he said. But Ulrich’s work shows that “from the perspective of history, any object is imbued with enormous power, and can teach us a lot about the world and about ourselves.”

Samanntha Tesch of Watertown brought a group of friends to the event.

“The presentation really made me think about the little tangible things that are around me every day: what they mean, and what future generations might think of them as artifacts of history,” she said. “There are things that, in a way, make me who I am. So I want to really see the things I experience around me, and think about what I want to preserve as my own history, too.”