The buildup of scar tissue, known as fibrosis, has a number of consequences, including inflammation and reduced blood and oxygen delivery to the organ. Long term, the scar tissue can lead to organ failure and sometimes eventually death. It is estimated that fibrosis contributes to 45 percent of all deaths in the developed world.

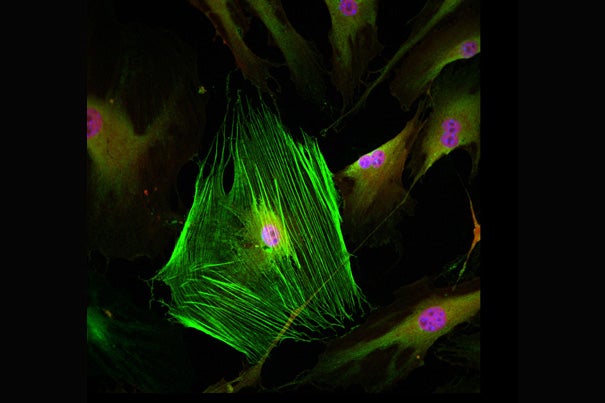

Credit: Rafael Kramann

The cellular origin of fibrosis

Harvard team identifies rare stem cells that give rise to chronic tissue scarring

Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at Brigham and Women’s Hospital say they have found the cellular origin of the tissue scarring caused by organ damage associated with diabetes, lung disease, high blood pressure, kidney disease, and other conditions.

The buildup of scar tissue, known as fibrosis, has a number of consequences, including inflammation and reduced blood and oxygen delivery to the organ. Long term, the scar tissue can lead to organ failure and sometimes eventually death. It is estimated that fibrosis contributes to 45 percent of all deaths in the developed world.

The researchers, led by Benjamin Humphreys, found that in mice, a rare population of stem cells located outside of blood vessels become myofibroblast cells that secrete proteins that cause scar tissue. Killing these stem cells prevents the deadly complications of fibrosis, the researchers report today in the journal Cell Stem Cell online. Rafael Kramann, a postdoctoral fellow in Humphreys’ lab, is the first author on the paper.

“Under normal circumstances, myofibroblasts stimulate wound healing, but when there’s an ongoing injury to an organ [such as the liver of a hepatitis C patient, the heart of a patient with high blood pressure, or the kidney of a patient with diabetes], these proteins clog up normal functioning,” said Humphreys, a Harvard Medical School associate professor at the Brigham, who leads the Harvard Stem Cell Institute Kidney Program.

The researchers are now in discussions with a pharmaceutical firm about screening for drugs that might target and shut off these fibrosis-causing stem cells in cases of chronic organ disease. The idea of using the stem cells as targets for drug discovery began with the formation — by Humphreys, Kramann, and Derek DiRocco — of MatriTarg Laboratories, the startup that won the 2013 Harvard Deans’ Health and Life Sciences Challenge.

“We wanted to know if eradication of this very small population of stem cells would improve organ function, and both kidney and heart were completely protected from developing fibrosis-related complications [such as kidney failure and heart failure],” said Humphreys, who also heads the Onco-Nephrology Program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “This provides an important proof of principle that drugs that target the stem cells could be therapeutic.”

The cellular origin of kidney fibrosis has long puzzled researchers. It was unknown which kinds of stem cells form myofibroblasts, and where these stem cells are located. One long-held hypothesis was that the stem cells that give rise to myofibroblasts are found in the bone marrow, but Humphreys’ research disproves that. By tagging a specific protein called Gli1 expressed by the myofibroblast-forming stem cells, the scientists showed that the cells are found on the periphery of blood vessels, and also reside within organs.

Humphreys does caution that the cell population his lab found is responsible for about 60 percent of all organ myofibroblasts, which means that they seem to be the most dominant source, but there may be other cells that also contribute to the myofibroblast population.

“We haven’t disproven every hypothesis, and our results do leave room for other cells that might contribute to fibrosis,” he said.

The Humphreys Lab collaborated with fellow Harvard Stem Cell Institute member Benjamin Ebert, an associate professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, on the work.

The research was supported by the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the American Heart Association, and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.